Gustav Mahler(1860 – 1911) once boldly proclaimed, “My time is yet to come,” a statement that foreshadowed the extraordinary legacy he would leave behind. His work serves as a bridge between the rich Austro-Germanic musical tradition and the daring experimentation of early 20th-century modernism, crafting a deeply personal and strikingly diverse musical universe.

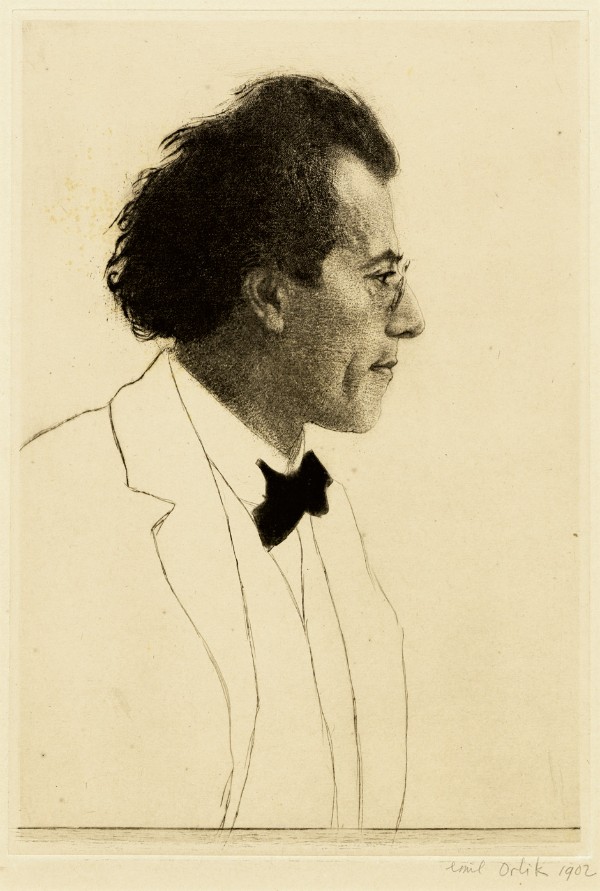

Gustav Mahler, 1902

Mahler’s compositions, with their vast emotional depth and evocative power, reflect not only the duality of his own personality but also the cultural and artistic anxieties of a world in rapid transformation. As Thomas Mann eloquently observed, Mahler expressed “the art of our time in its most profound and sacred form,” embodying a timeless humanistic vision.

Mahler’s music navigates the delicate balance between the idealistic aesthetics of Romanticism, where music transcends social and racial boundaries, and the challenges of an increasingly secular, industrialised, and fragmented modern era.

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 5, “Adagietto”

Musical Roots

Gustav Mahler was born on 7 July 1860 in the small village of Kaliště, a small rural village presently located in the Czech Republic. His parents, Bernhard and Marie, belonged to a humble, German‑speaking Jewish family striving to rise economically.

Bernhard ran a small distillery, and Marie, frail of health, brought sensitivity and a persistent sense of mortality to their household. The Mahler family endured an extraordinary tragedy. Of their fourteen children, only six survived past infancy, and Gustav himself constantly lived under the weight of poverty, ethnic alienation, and emotional tumult.

Essentially, Gustav grew up in Iglau (Jihlava), a thriving military and trade centre within the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Young Gustav was exposed to an infinite variety of music from all periods of history and every corner of the Empire.

Iglau was home to an amateur orchestra, a professional theatre, an opera and the church of St. Jakob, each richly contributing to the musical life of the community. In addition, Gustav experienced a wide range of music from local and extended folk traditions, which included characteristic dances and songs of Jewish, Moravian, Czech, Austrian, German and Bohemian origins.

Since Iglau was also a major staging point for the Austrian army, colourful military bands regularly participated in local festivals and engaged in concert activities. The memories of these musical impressions, alongside the stunning natural beauty of the Moravian countryside, would haunt Mahler for the rest of his life and dynamically reverberate in his compositions.

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 1, “Movement 4”

Conducting Odyssey

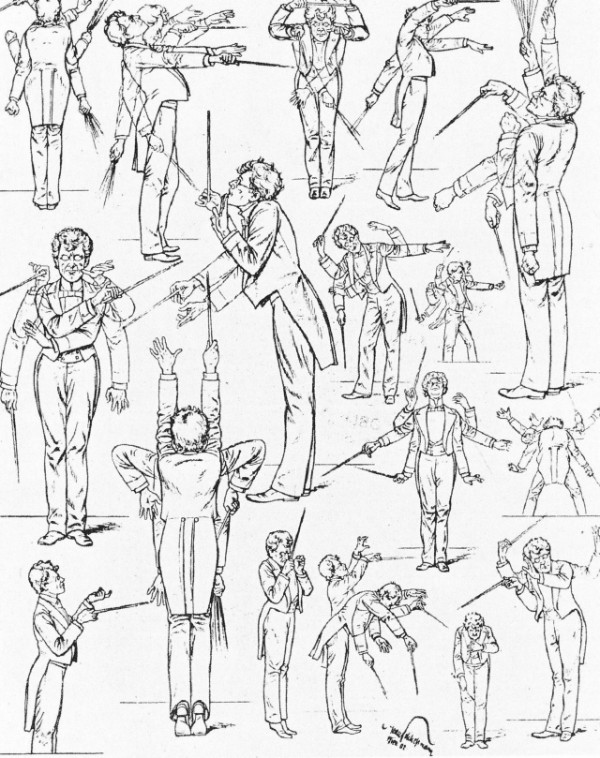

Caricature of Mahler conducting

Since Mahler was primarily engaged as a conductor, he had to compose in his spare time. Crisscrossing Europe, he held positions of ever-increasing importance at Bad Hall, Laibach, Olmütz, Prague, Leipzig, Budapest and Hamburg. Eventually, he assumed the directorship of the Imperial Opera in Vienna in 1897, undoubtedly the world’s most prestigious musical post.

His relationship with Vienna was at once triumphant and controversial, as he introduced new repertoire and reshaped the standard Classical Repertoire. His association with the supreme stage and costume designer Alfred Roller spawned more than 20 celebrated productions, and his administrative involvement restored financial stability to the organisation.

Although he converted to Catholicism in order to be eligible for the position, his Viennese tenure was a period of repeated battles with performers, administrators and a hostile and anti-Semitic press. Towards the end of his life, with offers from all major European musical institutions, he nevertheless turned towards the New World and accepted appointments with the Metropolitan Opera and subsequently the New York Philharmonic.

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 10, “Adagio”

Musical Vision

While his conducting engagements and interpretive expertise paid him a handsome salary that easily covered his material needs, he spiritually longed to express himself in his own music. During summer holidays, he withdrew to small composing huts in the Austrian countryside to reconnect with the sources of his inspiration and to scrutinise the cultural assumptions of the two great musical traditions, the Symphony and the German Lied, which he had inherited.

Mahler’s musical vision, which is instantly and immediately recognisable, came into focus in his first mature composition, the Songs of a Wayfarer. Employing a sharply characterised and eclectic mosaic of musical manners, Mahler juxtaposes the essential conflict of love of nature and a life of emptiness and despair.

Mahler also deeply engaged with the Wunderhorn anthology, a three-volume collection of anonymous German poetry. His interest was not rooted in its appeal to folk art or issues of national identity, but in the sense of alienation found in many of its poems. Full of irony, uncertainty, and the brevity of life, Mahler decided that these sentiments needed to be worked out in the symphonic medium.

Gustav Mahler: Songs of a Wayfarer

Blending Lied and Symphony

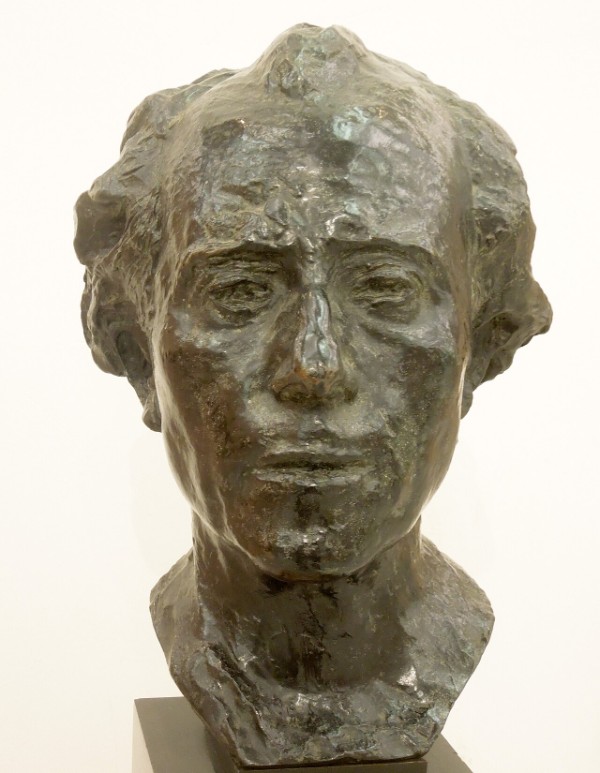

Auguste Rodin: Gustav Mahler, 1909

Musically expressing his position in the world, the Wunderhorn aesthetic not only spawned a series of poignant settings for voice and orchestra, but it also easily transferred into the symphonic context as well. Mahler’s integration of the Lied into the symphonic oeuvre blurred the distinction between the narrative and the dramatic and served him as a referential guideline for structurally formulating his symphonic thoughts.

From the spiritual and musical autobiography of his First Symphony, the search for assurance in the face of human mortality in the “Second,” the conception of existence in its totality in the “Third” to the naïve vision of heavenly bliss that concludes the “Forth,” Mahler followed an evolutionary path that not only expanded the emotional range and scope of the orchestra, but also gave voice to a stylistic plurality that was successfully resolved in conceptual narrative.

Mahler’s marriage to Vienna’s most eligible bachelorette, Alma Schindler, in 1901 instigated an immensely fulfilling period in his personal life. Nevertheless, his music took on a more ominous, grotesque and deeply pessimistic tone. Inspired by the personal directness, oriental flavour and intellectuality expressed in the poems by Friedrich Rückert, Mahler’s musical language now looked into the depths of the human soul, and confronted man’s destructive impulses and tendencies.

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 4, “The Heavenly Life”

From Street to Infinity

Mahler’s Fifth Symphony juxtaposes the most tragic and most joyful worlds of human emotion, while the “Sixth” presents a disturbing, menacing and unrelenting portrait of life without hope.

The “Seventh,” although praised by Schoenberg, was unable to answer the fundamental questions raised by the Sixth, and the monumental Eighth Symphony stands as a unique spiritual document that finds redemption in humanity’s quest for divine love and creative spirit. The lyrical Lied style, meanwhile, in both the Rückert Lieder and the Kindertotenlieder, is handled in a symphonic and contrapuntal fashion, emphasising linear clarity without sacrificing complexity.

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 8, “Finale”

Following the tragic death of his daughter from Scarlet fever, and concurrently receiving a medical diagnosis of heart disease in 1907, death was no longer an abstract concept but had solidified into a certain reality. In his most perfect synthesis of the Lied and the Symphony in Das Lied von der Erde, Mahler juxtaposes the bitterness of mortality and the sweet sensuous ecstasy of being alive.

Mahler’s “Ninth” presents a deeply moving descent into the darkest crevasses of hell, filled with abstracted and grotesquely distorted visions of his deteriorating mental state, while the unfinished “Tenth” is littered with agonising commentaries on the heart-wrenching discovery that Alma had been unfaithful.

The critic and scholar Paul Stefan probably summarised Mahler’s oeuvre most poignantly when he suggested, “his music begins on the street and ends in infinity.” As such, the extraordinary musical expressions of Gustav Mahler are not only capable of taking audiences on a musical quest of self-discovery; they also have fundamentally changed the way we think about music.

Gustav Mahler: Kindertotenlieder

Reception and Legacy

House Gustav Mahler

Gustav Mahler died of heart failure in Vienna on 18 May 1911, just weeks shy of his 51st birthday. During his lifetime, his music stirred a complex tapestry of reactions, marked by fervent admiration, puzzled bewilderment, and sharp criticism. Yet, his symphonies had been performed over 260 times across Europe, Russia, and America.

After his death, performances of his works waned but found enduring champions in Willem Mengelberg, Leopold Stokowski, and Adrian Boult. Before the Nazi ban on Mahler’s music as “degenerate,” conductors like Bruno Walter and Otto Klemperer kept his works alive in Germany.

The modern revival of Mahler’s music took place by the mid-20th century, when global audiences embraced the symphonies for their raw emotional power and prescient complexity.

Conductors and composers like Aaron Copland and Leonard Bernstein, alongside audiences, began to recognise Mahler as a trailblazer whose music deeply resonated with a world grappling with the upheavals of modernity.

Today, Mahler commands a near cult-like devotion, his works celebrated as timeless expressions of human struggle, hope, and transcendence, cementing his place as one of music’s most enduring visionaries.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter