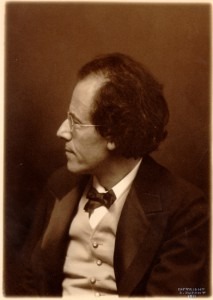

Gustav Mahler

credit : http://www.mahler.cz/en/gm/

The notated musical score requires not only realization, but also interpretation. In many cases, conductors will work with composers to clarify certain passages or to obtain a sense of musical meaning. However, equally important is the passing of knowledge about a given work from an older generation of composer to a younger generation of conductor, who eventually passes on this knowledge to the listener. In rare cases this communicative effort between conductor and composer is preserved as a phonographic record. Such is the case with Gustav Mahler and the Dutch conductor Willem Mengelberg, who was particularly known for his interpretation of works by Richard Strauss and Gustav Mahler. In fact, Mengelberg met and befriended Mahler in 1902 and continued to invite him to the Concertgebouw. Mahler edited some of his symphonies while rehearsing with the orchestra, and in 1920, Mengelberg instituted a Mahler Festival in which all the composer’s music was performed in nine concerts. Mengelberg also made a number of recordings with the Concertgebouw Orchestra, among them the 4th Symphony by Mahler, recorded in 1939. Mengelberg’s interpretation frequently uses extensive string portamento — a special effect he meticulously cultivated with the Concertbebouw — and employs lush and varied tempo inflections, that according to Mahler, pinpointed emotional climaxes in his music.

The folksong qualities and disarming sincerity of the Wunderhorn lyrics offered Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) the possibility of inventing a new type of Lied. Attracted by the simplicity and musicality inherent in the texts, Mahler composed diatonic and direct settings that reflected a hint of sophistication. Supported by an orchestral accompaniment that was economical in terms of size and scoring, Mahler created a chamber-like quality that proved fundamental to his own musical development. His integration of the Wunderhorn songs into the symphonic oeuvre blurred the distinction between the narrative and the dramatic, and served him as a referential guideline for structurally formulating his symphonic thoughts. Two orchestral adaptations from the Wunderhorn surfaced in the “Resurrection” Symphony, and the fifth movement of his 3rd Symphony provided a choral setting of “Es sungen drei Engel” (Three Angels Sang). In fact, the monumental 3rd Symphony was originally slated to conclude with a further Wunderhorn setting—already fully realized and scored—but Mahler eventually decided against its inclusion. This movement, originating in the song “Das himmlische Leben” (The heavenly life) composed in 1892, would subsequently become the Finale of his 4th Symphony. This meant, that Mahler had to plan the symphonic narrative backwards, starting with the already existing Finale and composing preceding movements that thematically and aesthetically were to build on the musical and philosophical materials originating in the childlike vision of heaven. That fact was not lost on a rather hostile Viennese press. A critic, with typical anti-Semitic propensity complained, “this 4th Symphony has to be read from back to front, like a Hebrew Bible”. Mahler essentially created a symphony that explored the road from experience to innocence, from complexity to simplicity, and from earthly life to heaven. The most notable event in the reception history of this work occurred in October 1904 at the Concertgebouw Orchestra in Amsterdam, with a provocative double billing. Championed by his friend Willem Mengelberg, Mahler conducted the following programme: Mahler Symphony No 4 – Intermission- Mahler Symphony No 4.

The opening “Bedächtig, nicht eilen” (Moderately, not rushed) begins the journey towards innocence with the sounds of sleigh bells and chirping flutes. This overtly simplistic evocation of nature prompted Theodore Adorno to suggest that the opening sleigh bells are really the bells of a fool.” Mahler quickly introduces a seductive and childishly simplistic melody in the violins. This tune, however, is brusquely interrupted by the horn. In turn, the horn has to give way to the bassoon, and the violins trying to reassert their dominance disturb a gruff statement by the cellos and basses. This opening theme group features some of the most intricate motivic counterpoint in the symphonic repertoire. Mahler described it as “a thousand little pieces of a mosaic that make up the picture are shaken up and it becomes unrecognizable, as in a kaleidoscope, as though a rainbow suddenly disintegrated into millions of dancing drops so that the whole edifice seems to rock and evolve.”

Mahler considered the second movement “In gemächlicher Bewegung” (Leisurely moving) a dance of death. Originally called “Freund Hein spielt auf” (Friend Hein strikes up), it takes its inspiration from a self-portrait by Arnold Böcklin, in which the grim reaper fiddles into the painter’s ear. The central character in the musical depiction becomes the solo violin, tuned a whole tone higher to make it sound like a country fiddle. Played without vibrato to produce an emaciated and grave tone, the violin engages in a distorted and laboured conversation with the horn to create a rather grotesque Scherzo movement. This musical vision of death is twice contrasted by rustic and bucolic dances; both in the style of a “Ländler”.

The third movement marked “Ruhevoll” (Peacefully) builds on a set of Variations on two themes. Mahler once suggested that the gentle lullaby which opens the movement was inspired by “a vision of a tombstone on which was carved an image of the departed, with folded arms, in eternal sleep.” The second theme in minor mode emphasizes a lamenting quality, reflectively answering the sentiment expressed in the lullaby. Both themes, alternately, undergo a series of ingenious transformations, which grow successively shorter and more diverse in character. Sudden shifts in tempo signal a change to the major mode, and an enormous musical climax supported by blazing horns and thundering timpani strokes, welcomes the listener musically and spiritually in heaven.

Musically suggesting this proverbial arrival at innocence, the concluding “Sehr behaglich” (Very comfortably) opens with music from the final climax of the preceding movement, sounded by the solo clarinet. Once the voice has been introduced, the Wunderhorn text unfolds in successive stanzas, analogous to the singing of a hymn. Mahler supports this child-like vision of heaven — again juxtaposing the profane and sacred — with folk-like melodies that conclude with chorale-like endings. Corresponding interludes, in turn, feature the sleigh bell section heard at the very beginning of the first movement. Although seemingly ironic, Mahler’s musical setting ingeniously underscores the innocent sentiment and quality of the text. With the hushed sounds of an almost inaudible harp, the music gently fades away and concludes a symphony of subtle emotional expression and refined compositional technique.