Have you ever had a teacher who was a great musician, mystic, mentor, statesman and alchemist all at once? Pianist, György Sebők was such a man. When I first met him at Indiana University in Bloomington, Indiana in the late 1970’s he was already a legend. Little did I know that he would be a major influence on my life.

Have you ever had a teacher who was a great musician, mystic, mentor, statesman and alchemist all at once? Pianist, György Sebők was such a man. When I first met him at Indiana University in Bloomington, Indiana in the late 1970’s he was already a legend. Little did I know that he would be a major influence on my life.

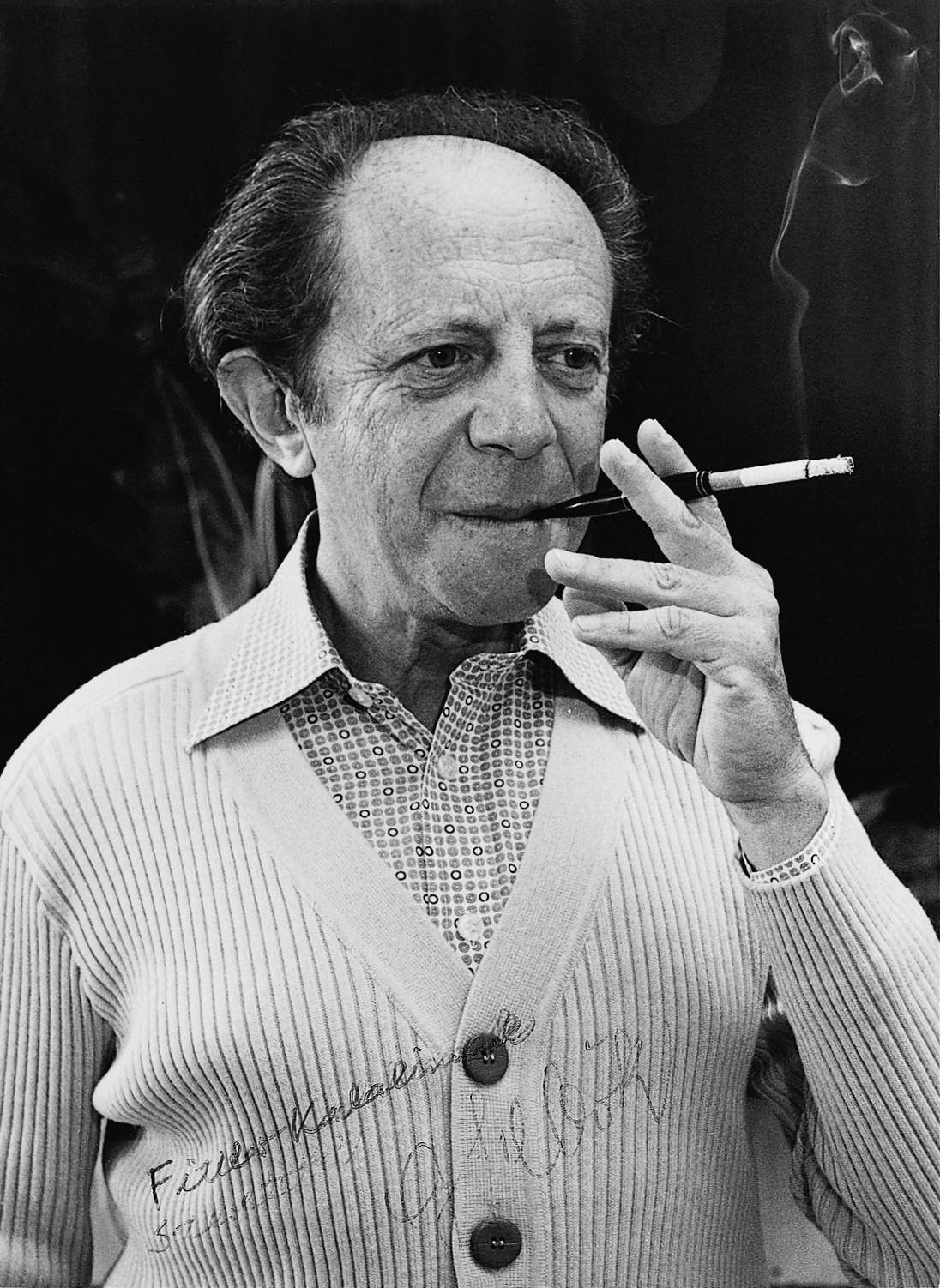

All my father cared about of course was that Sebők was Janos Starker’s chamber music partner, another fellow Hungarian and that Sebők, like my dad, always wore a suit and a tie. A diminutive man, his elegance was understated except for his ebony cigarette holder — which rarely left his hands. His playing was deep, profound, mesmerizing. He could play anything and everything from memory.

Sebők’s piano students found it hair-raising that Starker would poke his head into Sebők’s studio from time to time and they would burst into Hungarian banter. Sometimes they would forget that I knew the language. Once I sat next to Mr. and Mrs. Sebők at a concert. He was not pleased with the performer and said so to his wife using a few unrepeatable Hungarian words. Sebők turned beet red when he realized that I had understood.

One of Sebők’s first students in this country was Kenneth Huber, recently retired piano professor at Carlton College in Northfield, Minnesota. Ken was just out of high school — a young seventeen-year-old — when he heard that there was “a Hungarian named Sebők” who he should try to study with. Ken wrote to Sebők and subsequently traveled to Bloomington to play for him. Ken cowered in the hallways of the huge circular building until Sebők showed up. The master’s English was quite limited in those days and he was aloof. “So Play,” he said to Ken. Like any cocky young person, he chose an extremely difficult work for his audition — the Fête-Dieu à Séville by Isaac Albeniz. Sebők listened keenly. Afterwards, Ken told me, “He looked at me and said, ‘Wrong Rhythm.’ He paused. All my students are doctoral students. I don’t know if I have room for more.’

‘But I want to study with you.’

‘The dean decides. We shall see,’ and with that he waved for me to leave. He didn’t say a thing about my playing.”

Sebők’s class list was posted a few days later. The other freshmen were incredulous that Ken’s name appeared with the other privileged few.

The following week Ken went to his first lesson. He performed the entire Haydn Sonata in E–flat major from memory. Sebők got up slowly, looked at the front of the music, said, “Wrong edition. Get Urtext,” and unceremoniously opened the door to his studio for Ken to exit. “I was young. What did I know?” Ken told me. “I raced over to the music store and talked to the owner. ‘My teacher says I need Urtext. Is that the Peter’s edition?’ ”

Ken arrived for his second lesson Peter’s edition in hand. Sebök took the sheet music, leafed through the first pages and said, “Not Urtext. Get Urtext.” He flung the door to his studio open again.

Ken was quite anxious by the third lesson. He appeared at Sebők’s studio with yet another volume of the Haydn sonatas. Sebők once again flipped through the pages of the music. “Yes, Urtext. Play,” he said. Ken sat down at the piano almost melting with relief and performed the entire piece. At the end Ken looked up expectantly. “Wrong note. This is not high school,” Sebők said, and once again Ken was sent packing.

By now Ken was scared silly. “I had played the wrong edition; I had played a wrong note; I was sure I’d be thrown out! In hindsight I realize that Sebők wanted to clearly establish his standards presuming that a youngster like me needed to know where he stood.”

Sebők’s weekly chamber music master classes were packed and we all hung on his every word. Countless wisdoms stuck. Wrong notes were unacceptable. “You can’t make right music with wrong notes. If I can’t hit the right note, at least I can hit the wrong note at the right time. That’s not too bad. The worst is to hit the wrong note at the wrong time… When you look at a picture and it’s all there except for one tiny part you can still enjoy the whole picture. But if you look at a picture and it’s only half there it’s disturbing,” Sebők explained.

His ability to pinpoint the problem that interfered with your music making was uncanny. He rarely said, “Here’s the problem,” which in the long run is not helpful to a student who needs to be able to figure out issues on their own. He’d say, “The problem is not…” My playing changed forever when I heard him say, “If you control less, then you will get more. Control becomes a limitation.” He encouraged freedom and risk-taking. “There are many right ways: Having only one right way is an obsession. Two is a dilemma, and if you have three or more, you have choices. Then you are free.” Imagine how one’s playing can thrive with this advice!

Sebők had unique and a supremely creative way of looking at every situation. He was concerned most about who you were as an artist and how you conveyed what is behind and beyond the printed text on the page. That is the essence of performing and to do that takes constant probing.

No matter what instrument you played or even if you did not play a musical instrument, there were stunning and important lessons to be learned from Sebők.

“Change creates space within ourselves to discover something different. If you are afraid you need courage. If you are fearless you need nothing.”

http://www.sebokbook.com

Some of the quotes are from György Sebők—Words from a Master by Barbara Alex

De Larrocha plays Albeniz Iberia

famous interview with Sebők and he plays Busoni: