Frédéric Chopin

As a young critic, Robert Schumann famously introduced Frédéric Chopin to European audiences with the words, “Hats off, gentlemen, a genius!” In a later review on the Chopin piano concertos, Schumann suggested, “If the autonomous, mighty monarch of the North knew what a dangerous foe was threatening him in these utterly simple mazurka melodies, he would doubtless ban this music. The works of Chopin are cannons concealed amongst flowers.” Schumann’s enthusiasm of Chopin’s music also transferred to his own compositions, as one movement in the Carnaval, Op. 9 is titled “Chopin.”

Chopin, however, was less enthused about Schumann’s craft as he is reported to have uttered, “Carnaval is not music at all.”

Robert Schumann: Carnaval, Op. 9 “Chopin” (Boris Giltburg, piano)

At first glance, the relationship between Franz Liszt and Frédéric Chopin appears to have been rather cordial. Nevertheless, there was a substantial degree of underlying tension between the two foremost pianists on the Parisian musical stage. Chopin dedicated his first set of etudes to Liszt, who performed them frequently in his recitals. To the severe irritation of Chopin, however, Liszt would freely embellish said compositions. And in his first biography of Chopin, Liszt writes, “His character was indeed not easily understood. A thousand subtle shades, mingling, crossing, contradicting and disguising each other, rendered it almost undecipherable at the first view.” In the end, however, collegial respect triumphed. Chopin had composed 19 settings of polish poems, which were published posthumously in 1857 as his opus 74. Liszt paraphrased six of these vocal setting for piano solo and dedicated them to Princess Marie von Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst.

Franz Liszt: 6 Chants Polonaise, S480/R145 (Chopin) (Giovanni Bellucci, piano)

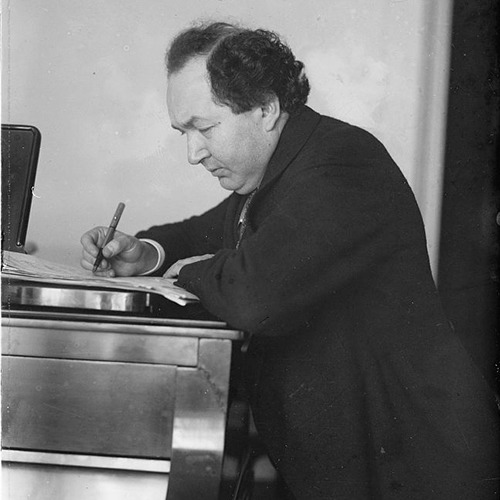

Anna Pavlova in the Ballets Russes ballet Les Sylphides (1909).

In 1892, Alexander Glazunov published an orchestral suite of Chopin’s piano music under the title Chopiniana, Op. 46. Rimsky-Korsakov, who conducted the premiere in December 1893, first introduced the work to the public. More importantly, however, it served the groundbreaking Russian choreographer and dancer Michel Fokine as the basis for his revolutionary ballet Les Sylphides. First staged at the Marinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg in 1907, the ballet had no running narrative but simply showcased a number of dancers dressed in traditional white ballerina skirts. Combining Chopin’s music with the grace and elegance of Anna Pavlova’s dance, audiences were given free reign to engage their imagination!

Alexander Glazunov: Chopiniana, Op. 46 (Moscow Symphony Orchestra; Vladimir Ziva, cond.)

Heitor Villa-Lobos is credited with merging the music of his native Brazil with musical elements and stylistic features from a central-European classical tradition. Born in Rio de Janeiro, but trained in the European Conservatory tradition, Villa-Lobos began to physically explore the unknown geographical and cultural interior of Brazil. On one of these expeditions, he even claimed to have been captured by cannibals. Be that as it may, in 1949 UNESCO commissioned a work commemorating the anniversary of Chopin’s death. Hommage à Chopin emerged almost spontaneously in two movements. “Nocturne” and “A la Ballade” reference Chopin’s style in piano figurations, thematic line, and accompaniment while still showcasing Villa-Lobos’s unique native musical heritage.

Heitor Villa-Lobos: Hommage à Chopin (Sonia Rubinsky, piano)

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Take a closer look at how 20th century composers responded to Chopin’s music.