When we hear an artist perform, we can’t help but wonder if there’s at least a dose of magic involved. The alchemy we witness though, is the culmination of years of concentrated training, experimentation, and study. Mastering our instruments is only the beginning. Over time, faced with a sheet covered in black markings, we learn to decode the pitches, the keys, and the rhythms on the page. Then follows the important work—getting beneath what we see on the page into the psyche of the composer. Musical terms, the international language of musical notation, give us clues to what the composer intended and helps a musician understand how to communicate the musical interpretation.

The terminologies we regularly use are from a multitude of languages including Italian, French, German, and English, and they cover a wide array of directions such as the rhythm, melody, harmony, dynamics, tempo, expression, style, and articulation. The composer will utilize markings in a musical shorthand or in actual words. But even these are not always the complete picture.

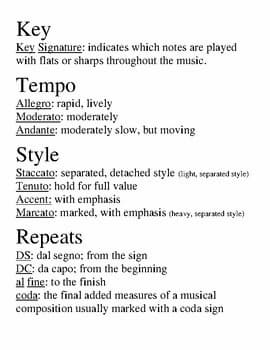

Musical terms: tempo

Take tempo. Many composers don’t indicate a metronome marking (the speed of a piece measured in beats per minute.) But even when there is a metronome marking it doesn’t give us the entire picture. A term, often in Italian, added to the beginning of a piece or a movement of a piece such as allegro, in combination with the time signature, can give us a great deal of information about the mood of a piece. While allegro can mean “quick” or “brisk”, it can also mean lively or cheerful. The following pieces, in 4/4, with four beats in a bar vary quite a bit in feel and mood.

Autumn from Vivaldi’s Four Seasons begins with a 4/4 Allegro, but so does the Brahms Cello Sonata in E minor op 38 Allegro non troppo, and Ravel’s Pavane for a Dead Princess.

Antonio Vivaldi: The Four Seasons: Violin Concerto in F Major, Op. 8, No. 3, RV 293, “L’autunno” (Autumn) – I. Allegro (Cho-Liang Lin, violin; Sejong; Anthony Newman, harpsichord)

Johannes Brahms: Cello Sonata No. 1 in E Minor, Op. 38 – I. Allegro non troppo (Gautier Capuçon, cello; Yuja Wang, piano)

Maurice Ravel: Pavane pour une infante défunte (arr. A. Koylove for orchestra) (Moscow Symphony Orchestra; Alexander Kopylov, cond.)

Other time signatures with four written beats in a bar such as a 12/8 or a 2/2 time signature, indicate a two feel or two large beats and these can also vary quite a lot in atmosphere.

The first movement of Brahms Symphony No. 4 marked Allegro non troppo, or not too brisk, begins in 2/2 (sometimes called cut time.) It has a gentle lilt. The fifth movement of Dvorak Suite in A major Op. 98 is marked in 2/2 allegro and you can feel and hear the difference.

Johannes Brahms: Symphony No. 4 in E Minor, Op. 98 – I. Allegro non troppo (London Philharmonic Orchestra; Marin Alsop, cond.)

Antonín Dvořák: Suite in A Major, Op. 98 (B. 184) – V. Allegro (Stefan Veselka, piano)

Other time signatures in a two feel such as Bach’s Gigue from his English Suite No. 2, is written in 6/8, with six eighth note beats in a bar. But so is the third movement from Beethoven’s Op. 135 String Quartet and it is radically different in character. Beethoven was very clear about the interpretation. It is not only marked 6/8 but also Lento Assai cantabile e Tranquillo—very slowly, with a singing tone, and tranquil—and that the movement should be played sotto voce or understated.

J.S. Bach: English Suite No. 2 in A Minor, BWV 807 – VI. Gigue (Ivo Pogorelich, piano)

Ludwig van Beethoven: String Quartet No. 16 in F Major, Op. 135 – III. Lento assai, cantante e tranquillo (The Danish String Quartet)

These words, often written below the staff, are an essential shorthand to steer a musician to the right atmosphere, quality of sound, and musical spirit.

A fortissimo passage may be marked risoluto, (or bold), or marcato (emphatic and accented) as in Elgar Cello Concerto movement IV. A melody might be marked moto espressivo, (very expressively), appassionato (with passion) or even con passione; while dolce, or dolcissimo should be played sweetly. Strauss II Waltz from Die Fledermaus is marked gracioso (grazioso) or to be played gracefully, smoothly, in an elegant manner.

Edward Elgar: Cello Concerto in E Minor, Op. 85 – IV. Allegro – Moderato – Allegro ma non troppo (Jacqueline Du Pré, cello; London Symphony Orchestra; John Barbirolli, cond.)

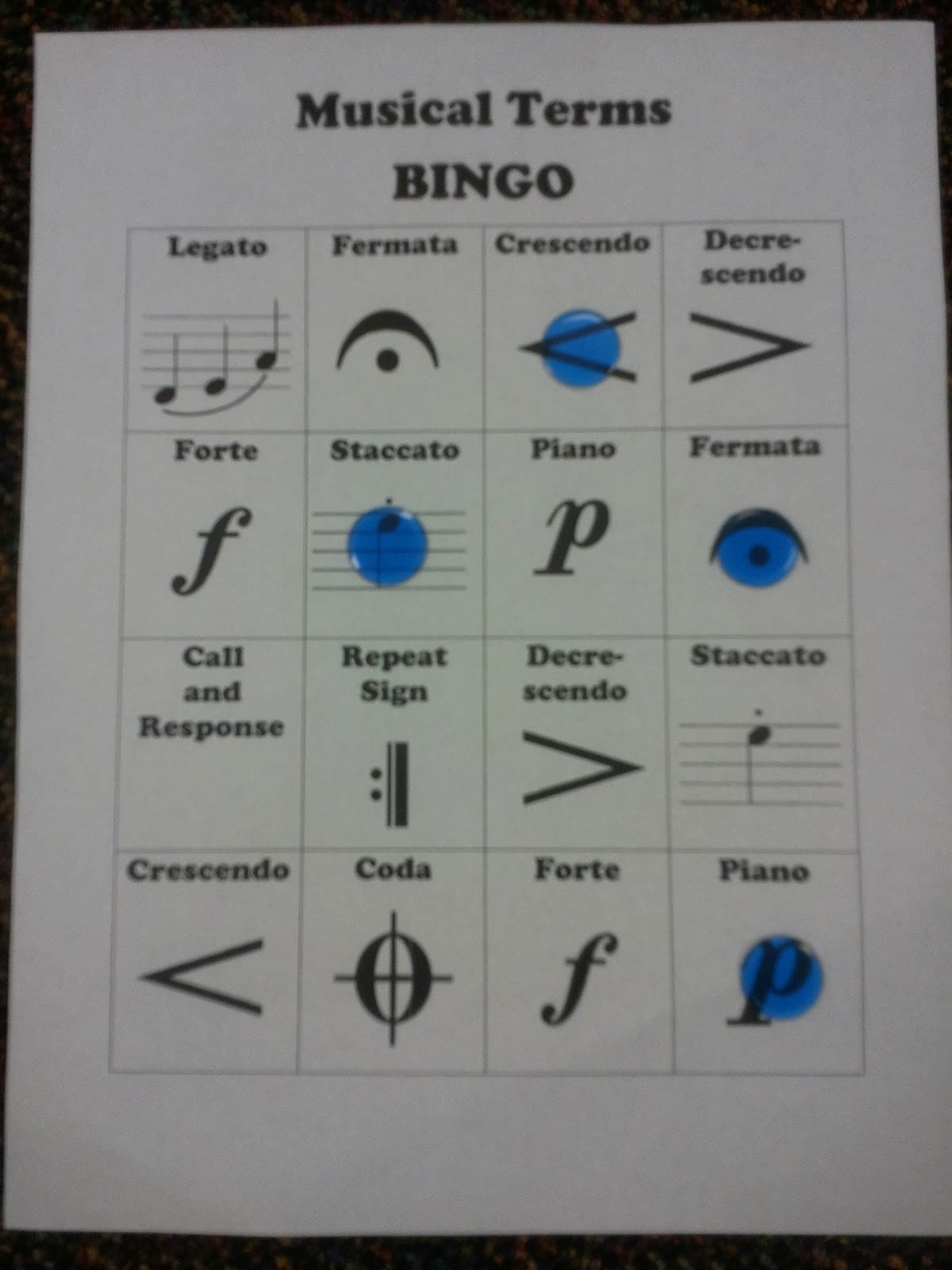

Musical terms bingo

As is typical with musicians, we like to kid around, and we might “misinterpret” or incorporate subtle misspellings to our musical terms to indicate other meanings! Here are two examples:

Apologgiatura: A piece you’re sorry you’re playing.

Approximatura: Notes played with intention and conviction even if they weren’t written by the composer.

More can be seen at “Playing With Musical Terms”.

How we produce these varying sounds is a lifelong exploration. For string players, our bow is our voice. We will spend years refining our bow strokes, to emulate the sounds a singer might make. Some of the variables are the bow speed, the amount of bow used, the type of articulation, the placement of the bow between the fingerboard and the bridge, and the weight of the arm. Our left-hand vibrato, fluency, and shifting or moving around are also very important for expressing musical ideas.

To complicate matters, the time signature, the tempo markings, the musical terminology, and even the dynamic indications will vary with the period of music and the composer whose music we are playing. Hence, it’s not enough to study the musical terms. We also need to be familiar with the approach and style of music from different musical periods. Baroque music is played radically differently than the impressionistic music of Ravel and Debussy, or the romantic music of Tchaikovsky, Brahms, and Strauss, and we would utilize different bowing techniques, vibrato, and articulations depending on the style of the music.

Now are we ready to appear before the public? Even among the most accomplished players one can find quite a variation of tempo and interpretation. And that is the inexplicable artistic aspect and alchemy of performing. Each musician has a distinct personality and as re-creators, we bring our own unique voice to the music, with the ultimate goal of communicating wordlessly to audience members.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter