Have you ever heard the song Gloomy Sunday, the 1933 tune composed by Hungarian pianist and composer Rezső Seress? This song is said to be the saddest tune ever composed, and is rumoured to have sparked hundreds to commit suicide. The melancholic song was inspired by Seress’ emotions as he lived through the Great Depression and the political upheaval leading to the Second World War, and solemnly reflects the horrors of modern culture. As a result, Gloomy Sunday was initially banned by Hungarian officials.

Have you ever heard the song Gloomy Sunday, the 1933 tune composed by Hungarian pianist and composer Rezső Seress? This song is said to be the saddest tune ever composed, and is rumoured to have sparked hundreds to commit suicide. The melancholic song was inspired by Seress’ emotions as he lived through the Great Depression and the political upheaval leading to the Second World War, and solemnly reflects the horrors of modern culture. As a result, Gloomy Sunday was initially banned by Hungarian officials.

In the United States, the song became known as the “Hungarian suicide song”. The composer himself ended his life in 1968, choking himself to death with a wire after a previously failed suicide attempt. However, while urban legends associate the song with various suicides, many of the claims are actually unsubstantiated. In fact, it is said that the suicide myths were propagated as a deliberate marketing campaign by American music companies to promote the song.

The story of Gloomy Sunday demonstrates how music can affect the way people feel. But how does music arouse our emotions? Are the emotions conveyed in music universal, or are they affected by our cultural upbringing?

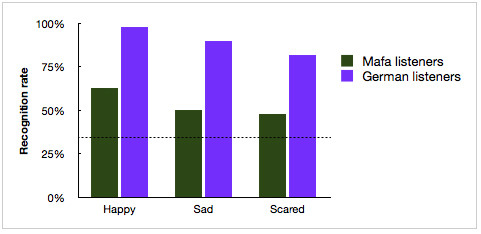

Researcher Thomas Fritz decided to explore these questions on a visit to the Mafa people, one of the most culturally isolated groups of people residing in the Mandara Mountains. Although the Mafa people have their own musical traditions, most have never been exposed to western culture or music. Hence, Fritz conducted an experiment that involved showing Mafa and German listeners images of faces expressing each of three emotions—happiness sadness or fear. The participants were instructed to point out which face they related to while listening to different clips of music. The results are shown below:

Although the more dramatic results among German listeners suggest some cultural influence in how we “feel” music, the results show that at least some portion of music appreciation may be universal. It appears that, even if one cannot completely understand or appreciate a certain culture’s music, very few people would mistake fast, rhythmic music as “sad”, or lullabies as dance music. This has been further supported by other experiments that depict how the brain reacts when listening to different types of music. So even though the Mafa tribe in Africa had never listened to western music, they can, like most people, differentiate between the different emotions expressed.

In another experiment, Bach and Mahler’s music were played to non-musician volunteers who had their brains scanned , in order to see which parts of their brains were activated when pleasant and unpleasant tunes were played. Another group of researchers played 60 excerpts of western classical music and asked participants to rate their level of happiness. (100—happy, 50—neutral, 0—sad) From these results, researchers identified 5 songs that were generally recognized as happy songs, 5 sad ones and 10 ‘neutral’ songs. These 20 songs were then played to another 16 healthy individuals who also had their brains scanned while listening.

Flores-Gutiérrez’s results showed that the left cortical network of the brain was activated by pleasant feelings across participants. In contrast, unpleasant emotions involved the activation of the right frontopolar and paralimbic areas. What this means, is that happy, sad or neutral emotions of music activate different parts of the brain. For example, listening to “happy” music causes reactions in the brain similar to receiving a reward, or eating delicious food. They show that music can indeed evoke emotions to affect the way we feel. Likewise, it has also been discovered that patients who had these parts of their brains damaged or removed were subsequently unable to identify these emotions.

By understanding the power of music on the brain, it is no wonder that many shopping centers like to play light, happy music to help customers relax while shopping. Likewise, motivational music is used to boost morale and help soldiers get through hard times. In hospitals, peaceful background music helps evoke a sense of calmness in sick patients. Seen this way, music can also be used to control human behaviour.

Perhaps a more positive way of looking at this issue is to turn to Aristotle’s point of view, who considered the essence of music imitation. His view looked at how rhythm and melody can supply the likenesses of anger and gentleness, of courage and temperance and all qualities of character contrary to these. And through listening, music helps our souls to undergo change . He further discussed the function and benefits of music with a view to its use in education, and concludes that “Music has a power of forming the character, and should therefore be introduced into the education of the young.”

Indeed, music is really an imitation of the things closest to life. However, some things cannot be explained or expressed through language. Music, on the other hand, can supersede language, and hence only by going beyond language, can we really understand why music gives us these feelings.

References: Gloomy Sunday, Music on the brain: Researchers explore the biology of music, Babies Remember Music Heard in the Womb, Even isolated cultures understand emotions conveyed by Western music

Photo credits: livefilestore.com, scienceblogs.com

More Sciences

-

Music as Medicine: How Sound Affects Our Mental Health Find out what neurologists have discovered about your playlist!

Music as Medicine: How Sound Affects Our Mental Health Find out what neurologists have discovered about your playlist! -

Conquering Stage Fright – Scientific Methods to Overcome Performance Anxiety Learn how to use simple cognitive reframing to transform performance anxiety

Conquering Stage Fright – Scientific Methods to Overcome Performance Anxiety Learn how to use simple cognitive reframing to transform performance anxiety -

Mental Training for Musicians – Unlocking Peak Performance Your mind might be the most important instrument you own!

Mental Training for Musicians – Unlocking Peak Performance Your mind might be the most important instrument you own! -

Once More, With Feeling: Music, Dopamine, and the Brain Why can you listen to your favorite song on repeat without getting tired of it?

Once More, With Feeling: Music, Dopamine, and the Brain Why can you listen to your favorite song on repeat without getting tired of it?

Very interesting…but who decided which Bach and Mahler melodies were pleasant and unpleasant?