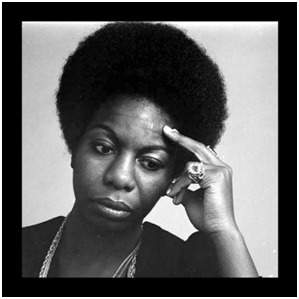

Nina Simone

I explain: a photocopier does not really replicate anything – it does not really achieve repetition: each copy is slightly different from the previous copy, and all copies are different from the original. Similarly, a record player does not repeat what a musician played during the recording; there are several differences, small or large, which any ear can pick up. In the same way, a musician playing a piece which he or she has played before cannot really repeat it.

The same applies to life: how many times do we try to repeat a pleasant experience we once had only to be frustrated by the results? A party, a trip, a meal… the more obsessively we try to recreate the details of the experience, the more we are bound to fail in re-experience the pleasure we once felt. Because, ultimately, what had made the experience pleasant was not anything which could be replicated: it was not that one restaurant, that one piece of music, that one hotel. What made it special was our way of feeling about it, our own individual response to it.

Kierkegaard differentiated true repetition (henceforth Repetition) from recollection, which is the attempt to imitate a remembered thing, we have idealised ideal. In trying to replicate that recollected ideal, the musician performs like a record player. The same applies the life outside music, where a recollecting person gets stuck in an artificial life: clinging to their egos, to images they have created of themselves and that they feel now they must replicate over and over and over. This is photocopier-living; recollection. The endless pursuit of an ideal which has been (or which we imagine that was) and which we want to replicate.

In contrast, Repetition accepts that what makes life special is not the external things, but the internal thing. That acceptance comes easily since, as we have seen, we would never be able to replicate the external things perfectly anyway. Fortunately, the only thing which we can Repeat is in our grasp – ourselves: the only possible repetition is of oneself , or to be oneself to such an extent that that is the only thing one can be, whatever happens outside oneself. And, of course, our “selves” change over time as we learn and experience life. So that repetition of the self is always expressed in a different way, but its nature remains the same. To be oneself, free of the molds one has learnt (and recollected) means to achieve a type of originality which is often called improvisation. That originality, therefore, depends on Repetition, on not getting stuck in any recollected ideal along the way.

Hence Kierkegaard’s comment that the key to Repetition is the “Gemüth” (a concept which itself could take – and has taken – many books to discuss, but which we may use as shorthand for some sort of synthesis of self-consciousness). That “Self” must remain itself, not painted over by some external ideal, if our creation is to be true and original. The originality with which Repetition repeats itself is the point, Kierkegaard wrote: that is, maintaining the Self free of recollection-style pursuits, keeping it original. Without originality, he concluded, “repetition is merely pedantry”. Pedantry is an apt word, since that is precisely what the attempt to recreate a recollected ideal ultimately brings; a little dogma of one’s own.

For the musician, that is the achieving that state where improvisation is possible. The learning, practicing and rehearsing… that is recollection. To go beyond that into true expression of one’s Self means to lower one’s barriers – the external and the internal ones – and allow for true interaction with one’s environment. That process of improvisation necessitates a learned surrender, a skillful release. That might just lead to a special moment like the one you were trying to recreate in the first place.

Nina Simone’s ‘I’ll look around improvisation’