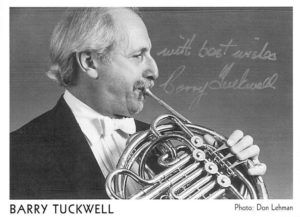

Barry Tuckwell

Barry Tuckwell (1931-2020), widely acclaimed as the preeminent horn player of his generation, has died on 16 January 2020 at a hospital in Melbourne. I still remember seeing and hearing him perform at a concert in Amsterdam, and like the rest of the audience I was immediately mesmerized by his infectious and humorous stage persona and the dazzling technical quality of his playing. Absolutely flawless, Tuckwell was capable of playing the most forceful and sparkling fanfares and simultaneously he could produce silken musical lines of sublime delicacy. Asked about his mastery of this recalcitrant instrument Tuckwell once said in an interview, “You put air in there, and God knows what happens to it on the way. With a bit of luck, the air reaches the other end of the instrument as music.” Believe me, luck had nothing to do with Tuckwell’s performances. A critic once exclaimed, “If the hunter had played like Tuckwell, the deer would have died from ecstasy.”

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Horn Concerto No. 4, “Rondo”

A native of Australia, Tuckwell compared playing the horn to “driving a Mercedes at top speed on a slick road, with even the slightest mistake having disastrous consequences.” When he reflected on the difficulty of playing the horn, Tuckwell explained “horn-players have evolved a kind of freemasonry over the years, a fierce sense of loyalty. If someone is having a bad night, the others will do what they can to cover him. Because nobody, but nobody, else really understands our problems.” Tuckwell grew up in a musical home, but he showed only moderate musical promise playing the piano, the violin and the organ. But when he picked up his French horn at the age of 13, he knew that he had found his calling. “The horn chose me,” Tuckwell recalled, “Right from the beginning, it was something I knew I could do.” Within six months he began to play professionally with the Melbourne and Sydney symphony orchestra. Tuckwell left for Britain in 1950, playing with the Hallé Orchestra under John Barbirolli in Manchester and the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra under Charles Groves. He was only 24 when he became principal horn player with the London Symphony Orchestra, a post he held of 13 years.

A native of Australia, Tuckwell compared playing the horn to “driving a Mercedes at top speed on a slick road, with even the slightest mistake having disastrous consequences.” When he reflected on the difficulty of playing the horn, Tuckwell explained “horn-players have evolved a kind of freemasonry over the years, a fierce sense of loyalty. If someone is having a bad night, the others will do what they can to cover him. Because nobody, but nobody, else really understands our problems.” Tuckwell grew up in a musical home, but he showed only moderate musical promise playing the piano, the violin and the organ. But when he picked up his French horn at the age of 13, he knew that he had found his calling. “The horn chose me,” Tuckwell recalled, “Right from the beginning, it was something I knew I could do.” Within six months he began to play professionally with the Melbourne and Sydney symphony orchestra. Tuckwell left for Britain in 1950, playing with the Hallé Orchestra under John Barbirolli in Manchester and the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra under Charles Groves. He was only 24 when he became principal horn player with the London Symphony Orchestra, a post he held of 13 years.

Richard Strauss: Horn Concerto No. 1 in E-Flat Major, Op. 11 (Barry Tuckwell, horn; Royal Philharmonic Orchestra; Vladimir Ashkenazy, cond.)

For a number of years Tuckwell acted as the director and chairman of the LSO, but administrative squabbles hastened his departure from the orchestra in 1968. Ready to pursue a solo career, he founded the Barry Tuckwell Wind Quintet and he was already highly sought after as a soloist. He quickly became the leading interpreter of a select and exquisite horn repertoire, focusing on the four concertos by Mozart, two by Strauss and a number of works by Gliere, Cherubini, Bruckner, Brahms, Ravel and Shostakovich. A critic suggested that Tuckwell “almost never misses a note. His ability might be compared to that of a coloratura soprano. His tone is rich, and variously colored and shaded. His legato exhibits a singing line and a faultless feeling for accent and phrasing. His staccato attacks, made with the help of the tongue, are firm, and where desired remarkably rapid, and his articulation has enormous variety.”

For a number of years Tuckwell acted as the director and chairman of the LSO, but administrative squabbles hastened his departure from the orchestra in 1968. Ready to pursue a solo career, he founded the Barry Tuckwell Wind Quintet and he was already highly sought after as a soloist. He quickly became the leading interpreter of a select and exquisite horn repertoire, focusing on the four concertos by Mozart, two by Strauss and a number of works by Gliere, Cherubini, Bruckner, Brahms, Ravel and Shostakovich. A critic suggested that Tuckwell “almost never misses a note. His ability might be compared to that of a coloratura soprano. His tone is rich, and variously colored and shaded. His legato exhibits a singing line and a faultless feeling for accent and phrasing. His staccato attacks, made with the help of the tongue, are firm, and where desired remarkably rapid, and his articulation has enormous variety.”

Johannes Brahms: Trio for Violin, Horn and Piano, Op. 40 (Barry Tuckwell, horn; Itzhak Perlman, violin; Vladimir Ashkenazy, piano)

Tuckwell recorded prolifically, with more than 50 solo discs to his credit that cover the full repertory from Telemann to Richard Strauss. A good many contemporary composers also wrote works for Tuckwell, including Oliver Knussen, Don Banks, Richard Rodney Bennett, Gunther Schuller, Iain Hamilton, Robin Holloway and Thea Musgrave. When the solo part of Musgrave’s Horn Concerto was subjected to ironic commentary, Tuckwell characteristically deflected all criticism by commenting, “There’s a horn player at every exit so no one can leave.” Considered the most recorded hornist in history, Tuckwell also pursued conducting opportunities. He appeared with leading orchestras in Europe and the United States, and was Chief Conductor of the Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra for four seasons. In 1982, he became the founding music director of the Maryland Symphony Orchestra in Hagerstown. By all accounts, Tuckwell was an inspiring teacher known for his master classes, and he wrote three important books on the horn and horn playing. He retired from the stage in 1997 and eventually returned to his native Australia. He died in Melbourne, aged 88, of complications from heart disease.

Tuckwell recorded prolifically, with more than 50 solo discs to his credit that cover the full repertory from Telemann to Richard Strauss. A good many contemporary composers also wrote works for Tuckwell, including Oliver Knussen, Don Banks, Richard Rodney Bennett, Gunther Schuller, Iain Hamilton, Robin Holloway and Thea Musgrave. When the solo part of Musgrave’s Horn Concerto was subjected to ironic commentary, Tuckwell characteristically deflected all criticism by commenting, “There’s a horn player at every exit so no one can leave.” Considered the most recorded hornist in history, Tuckwell also pursued conducting opportunities. He appeared with leading orchestras in Europe and the United States, and was Chief Conductor of the Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra for four seasons. In 1982, he became the founding music director of the Maryland Symphony Orchestra in Hagerstown. By all accounts, Tuckwell was an inspiring teacher known for his master classes, and he wrote three important books on the horn and horn playing. He retired from the stage in 1997 and eventually returned to his native Australia. He died in Melbourne, aged 88, of complications from heart disease.