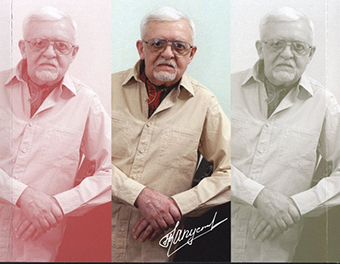

Nikolai Kapustin

Until very recently, the music of Russian composer and pianist Nikolai Kapustin (1937-2020) was virtually unknown to Western audiences. Although he has authored more than 150 works—among them several piano concertos and chamber compositions—Kapustin has been stubbornly unwilling to participate in the populist marketing strategies that have unfortunately allowed a whole host of musical vaudeville simpletons to invade our concert stages. Rather, the composer has quietly perfected a convincing and idiomatic fusion between the language of jazz and the structural demands of classical music. Trained as a classical pianist, he quickly became interested in jazz, particularly the music and performance style of Oscar Peterson. Skillfully blending and transcending both musical traditions, his compositions present a unique amalgamation of the virtuosity of classical pianism and the improvisational nature of jazz.

Nikolai Kapustin: 8 Concert Etudes, Op. 40 (Sukyeon Kim, piano)

Nikolai Kapustin was born on 22 November 1937 in the small city of Horlivka, situated in the Donetsk province of Eastern Ukraine. He initially took piano lessons from the violinist Ivanovich Vinnichenko, engaged to teach his sister, who realized the child’s huge potential as a pianist. However, it was Lubov Frantsuzova, a graduate from the St Petersburg Conservatory, who prepared Kapustin for the entrance exam to the Moscow Conservatory. Kapustin was immediately accepted into the preparatory class of Avrelian Grigoryevich Rubakh, a student of Felix Blumenfeld, who had also taught Vladimir Horovitz and Simon Barere. Kapustin was not merely interested in becoming a pianist; he was also drawn to improvisation and composition. He composed his first piano sonata at the age of 13 in a traditional classical style, and he credits Rubahk as a key figure in his life. “He taught me how to play the piano.” The “Post-Stalin Thaw” accorded greater freedom to many aspects of Russian life, and Jazz became a symbol of freedom. Kapustin remembered, “in the 50s it was completely prohibited, and there were articles in our magazines that said it was typical capitalistic culture, so we had to throw it away.”

Nikolai Kapustin was born on 22 November 1937 in the small city of Horlivka, situated in the Donetsk province of Eastern Ukraine. He initially took piano lessons from the violinist Ivanovich Vinnichenko, engaged to teach his sister, who realized the child’s huge potential as a pianist. However, it was Lubov Frantsuzova, a graduate from the St Petersburg Conservatory, who prepared Kapustin for the entrance exam to the Moscow Conservatory. Kapustin was immediately accepted into the preparatory class of Avrelian Grigoryevich Rubakh, a student of Felix Blumenfeld, who had also taught Vladimir Horovitz and Simon Barere. Kapustin was not merely interested in becoming a pianist; he was also drawn to improvisation and composition. He composed his first piano sonata at the age of 13 in a traditional classical style, and he credits Rubahk as a key figure in his life. “He taught me how to play the piano.” The “Post-Stalin Thaw” accorded greater freedom to many aspects of Russian life, and Jazz became a symbol of freedom. Kapustin remembered, “in the 50s it was completely prohibited, and there were articles in our magazines that said it was typical capitalistic culture, so we had to throw it away.”

Nikolai Kapustin: Piano Quintet, Op. 89 (Alexander Chernov, violin; Vladimir Spektor, violin; Svetlana Stepchenko, viola; Alexander Zagorinsky, cello; Nicolai Kapustin, piano)

Kapustin: Eight Concert Etudes for piano – “Prelude”

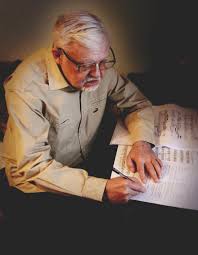

During his study at the Moscow Music College, Kapustin got acquainted with Louis Armstrong, Glenn Miller, Benny Goodman and Nat King Cole on the radio station “Voice of America.” It inspired Kapustin to start performing as a jazz pianist, and he organized a Jazz Quintet that appeared in one of the most exclusive Moscow restaurants. Eventually, the performance of that band was broadcast on the “Voice of America” as well. Graduating from the Moscow Music College in 1956, Kapustin entered the Moscow Conservatory and he was accepted into the class of legendary pianist Alexander Goldenweiser. Goldenweiser was a student of Ziloti, Pabst, Arensky, and Ippolitov-Ivanov, and he frequently told his students “I was sitting in lectures with Scriabin, Rachmaninoff, and Medtner.” Goldenweiser was clearly impressed with Kapustin’s pianism, but he was exclusively interested in classical music. At one time Kapustin mentioned in an interview, “he was not sure that Goldenweiser had ever heard the word jazz.” Kapustin had trained to become a virtuoso performer, and he graduated from the Moscow Conservatory with the second piano concerto by Bartók. However, he eventually rejected the idea of becoming a traveling virtuoso and appeared as the pianist in Oleg Lundstrem’s Symphony Orchestra of Light Music. Kapustin mentioned in an interview, “Eleven years of work with Lundstrem became my Second Conservatory as it involved a large amount of arranging and performing.”

As a composer, Kapustin clearly belongs to the “Third Stream.” At the heart of this concept is the notion that any music stands to profit from a confrontation with another. Composers of Western art music can learn a great deal from “the rhythmic vitality and swing of jazz, while jazz musicians can find new avenues of development in the large-scale forms and complex tonal systems of classical music.” In the 1960s, Kapustin attempted to interpret the traditions of George Gershwin and Duke Ellington fusing it with Russian piano music. In the 1970s he focused on a fusion style based on an amalgamation of elements of jazz and rock, European formal music and non-European folklore. In his chamber music the classical structures are radically transformed by principles which are specific to jazz thinking, namely improvisation and refinement in the development of rhythm and modal harmony. Kapustin regarded himself as a composer rather than a jazz musician. “I was never a jazz musician. I never tried to be a real jazz pianist, but I had to do it because of the composing. I’m not interested in improvisation – and what is a jazz musician without improvisation? All my improvisations are written, of course, and they became much better; it improved them.” An unassuming man and composer, Nikolai Kapustin died on 2 July 2020 in Moscow at the age of 82.

As a composer, Kapustin clearly belongs to the “Third Stream.” At the heart of this concept is the notion that any music stands to profit from a confrontation with another. Composers of Western art music can learn a great deal from “the rhythmic vitality and swing of jazz, while jazz musicians can find new avenues of development in the large-scale forms and complex tonal systems of classical music.” In the 1960s, Kapustin attempted to interpret the traditions of George Gershwin and Duke Ellington fusing it with Russian piano music. In the 1970s he focused on a fusion style based on an amalgamation of elements of jazz and rock, European formal music and non-European folklore. In his chamber music the classical structures are radically transformed by principles which are specific to jazz thinking, namely improvisation and refinement in the development of rhythm and modal harmony. Kapustin regarded himself as a composer rather than a jazz musician. “I was never a jazz musician. I never tried to be a real jazz pianist, but I had to do it because of the composing. I’m not interested in improvisation – and what is a jazz musician without improvisation? All my improvisations are written, of course, and they became much better; it improved them.” An unassuming man and composer, Nikolai Kapustin died on 2 July 2020 in Moscow at the age of 82.