Fernand Khnopff: Listening to Schumann

The Belgian Symbolist painter and sculptor Fernand Khnopff (1858-1921) is best known for his paintings that blend precise realism with a dreamlike atmosphere. His scenes are quite realistic, but then he mixes in motive and ideas from history and the arts. He was highly esteemed in Paris and London, and experts “consider him one of the pioneers of German Symbolism.” In fact, Gustav Klimt, who became aware of Khnopff through an exhibition in Vienna, was highly impressed. Initially, Khnopff devoted himself to portrait painting and naturalistic landscapes but his pictorial descriptions are not mere observations, but evocations. In his “Listening to Schumann” we immediately understand that somebody is playing the piano. The performer is not actually in the frame, but the visible outstretched right hand gives us the clear sense that there is actual sound. We also don’t see the face of the woman listening to the music, and it is impossible to gauge what composition is being played or whether she is listening at all. As the Symbolist manifesto suggested, “real world phenomena are not described for their own sake… They are perceptible surfaces created to represent their esoteric affinities with the primordial Ideals.” As viewers we are placed into an environment of heightened emotions, and the identification of the actual musical composition is not of primary importance.

Robert Schumann: Fantasia Op. 17

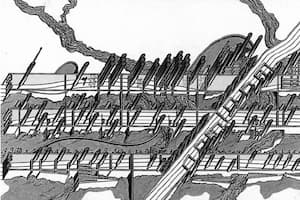

The measures of the concerto by Bloch that provided the layout for the Bloch City © Peter Cook

Architecture and music have long coexisted in a bond governed by their respective similarities. Recently, various academic approaches have investigated how contemporary architecture—explicitly declared to derive from musical compositions—pursue that intent.

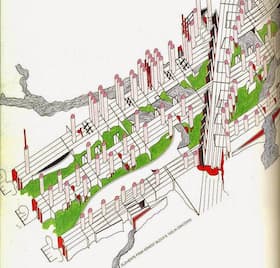

Bloch City with towers arranged on musical staffs © Peter Cook

The English architect Peter Cook, founder of the avant-garde architectural group “Archigram,” came up with a project that involved transferring the graphic form of Ernest Bloch’s “Concerto for Violin” into a composition of the plan for an ideal city. Cook did not rely on the sounding properties of the piece, but focused on the visual aspects of the score. “The notes become towers, the stave becomes a street, the supporting marking become walls… It was a series of short project on the idea of music as a direct architecture.”

Bloch City

As Cook explains, “as support for the melody, the extension of the staff is virtually infinite, and it represents the basis of the fluent character of verbal and sound expression: it provides a road in space and time to the completion of the musical experience.” The vertical aspects of harmony became tall buildings, and symbols of expressions highlight a formal discontinuity. Welcome to Bloch City.

Ernest Bloch: Violin Concerto (Oleh Krysa, violin; Malmö Symphony Orchestra; Sakari Oramo, cond.)

Homage to Beethoven sculpture

created by Markus Lüpertz

In 2020, the city of Bonn celebrated the 250th birthday of its most famous son, Ludwig van Beethoven. Among a whole host of arts projects, the city displays 12 statues of the composer in his hometown. The task of creating “Homage to Beethoven” fell upon Markus Lüpertz, one of Germany’s best-known contemporary artists. His sculptures exhibit suggestive power and archaic monumentality, and he “insists on capturing the object of representation with an archetypal statement of his existence.” And that’s certainly the case with the “Two-headed Beethoven.” It features an armless torso with a swollen head looking longingly into the distance, while sitting in front is a blue glowing bust of Beethoven. The sculpture is huge, standing almost 3 meters high and weighing 1,100 kilograms. Lüperz is a free jazz musician, who occasionally plays concerts with professional musicians. He freely admits that he is not a huge fan of Beethoven’s music, but that “the sculpture embodies the personality of the great composer.” Not necessarily wanting to provoke the public, he explains that “this artwork symbolizes Beethoven’s genius triumphing over adversity.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: String Quartet, Op. 132 “Heiliger Dankgesang”

Thomas Hardy

The English novelist and poet Thomas Hardy (1840-1928) was a Victorian realist in the tradition of George Eliot, and he was particularly fond of music. A number of poems have music and musicians as their theme, but one of his texts is closely matched to a specific piece of classical music. “Lines to a Movement in Mozart’s E-flat Symphony” was penned in 1898, and first published in “Moments of Vision” in 1917. Hardy changed the title from “Lines to a Minuet,” so the question of movement seems settled. However, since Mozart wrote a total of 4 symphonies in E-flat, there has been substantial debate which composition Hardy actually might have had in mind? Generally, it is taken to be Mozart’s Symphony No. 39, K. 543, but distinguished scholars have suggested, “The stanza form does not finally fit either minuet or trio of Mozart’s composition.” Maybe Hardy had a different movement in mind altogether, I let you be the judge.

Show me again the time

When in the Junetide’s prime

We flew by meads and mountains northerly! –

Yea, to such freshness, fairness, fullness, fineness, freeness,

Love lures life on.

Show me again the day

When from the sandy bay

We looked together upon the pestered sea! –

Yea, to such surging, swaying, sighing, swelling, shrinking,

Love lures life on.

Show me again the hour

When by the pinnacled tower

We eyed each other and feared futurity! –

Yea, to such bodings, broodings, beatings, blanchings, blessings,

Love lures life on.

Show me again just this:

The moment of that kiss

Away from the prancing folk, by the strawberry-tree!

-Yea, to such rashness, ratheness, rareness, ripeness, richness,

Love lures life on.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Symphony No. 39, K. 543