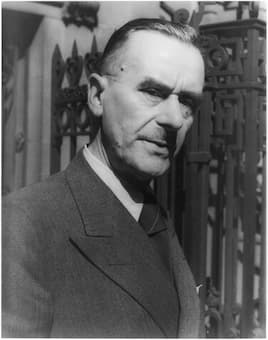

Thomas Mann

Thomas Mann (1875-1955) won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1929 for his highly symbolic, ironic and epic novels and novellas. A determined social critic, his writings provide biting insights into the psychology of the artist and the intellectual within the context of the tragic turmoil in the first half of the 20th century. His novel “Doktor Faustus” was published in 1947 and carries the subtitle, “The Life of the German Composer Adrian Leverkühn, told by a Friend.” Highly intelligent and creative, the young composer strikes a Faustian bargain for creative genius. He intentionally contracts syphilis, which deepens his artistic inspiration through madness.

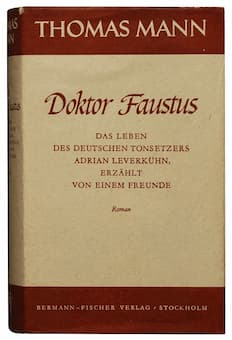

Thomas Mann: Doktor Faustus

Leverkühn becomes obsessed with the Apocalypse and the Last Judgment and with medieval legends, and he invents a completely new musical language, paralleling the 12-tone innovations of Arnold Schoenberg. Schoenberg, in fact was very annoyed that Mann had appropriated his technique and demanded an explanatory note acknowledging his invention. Leverkühn’s greatest work is the cantata “The Lamentation of Doctor Faust,” and after a chamber performance he collapses into incoherent madness. In preparation for the work, Mann studied musicology and communicated with living composers, including Igor Stravinsky, Arnold Schoenberg and Hanns Eisler. As such it is not surprising that Leverkühn’s cantata echoes the oratorio “Lamentatio Jeremiae prophetae,” composed in 1941 by Ernst Krenek. It combines Schoenberg’s 12-tone technique with modal/medieval counterpoint.

Ernst Krenek: Lamentatio Jeremiae Prophetae (Excerpt)

Nguyen Tuan’s statue in Greenville

The Vietnamese sculptor Nguyen Tuan is internationally known for his seemingly “weightless” figurative sculpture that merge Western techniques with traditional Eastern values. He coined the term “Existential Balance” to emphasis the importance of balance to human existence. As he writes, “once we embrace the true meaning of balance, we can come to terms with our own existence.” Every single one of his sculptures is the visual and tactile embodiment of his philosophy. Tuan’s father was a respected architect in Saigon, but after the fall of that city in 1975, freedom was replaced by oppression. Overnight, Tuan’s life was turned upside-down and his father instilled in him the love of sculpting. As Tuan explained, “Art is vital for me. It is almost a religion. It means to believe in people, in life, in love. It is a response to what is beautiful and simple. As an artist I do what I do for no other purpose than to express my feelings.”

Nguyen Tuan’s statue in Greenville

Music became an important aspect of his craft, and the sculpture of a male and female holding a violin and bow stands in downtown Greenville, South Carolina. “Reminiscence” presents human form in fluid motion and features the counterpoint and interaction of elements “that highlight the balance between darkness and light, masculine and feminine, rough and smooth, and often heaven and earth.” Tuan writes, “My sincere hope is that my art will successfully stimulate others to see the beauty of this world and to accept its balance. Balance is central to existence and is a basic human need; to lead a balanced life is to find its center.”

Claude Debussy: Clair de lune (arr. violin and piano) (Kyoko Yoshida, violin; Mitsutaka Shiraishi, piano)

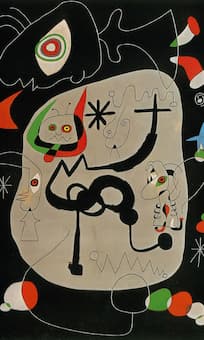

Joan Miró: Dancer Hearing an Organ

Playing in a Gothic Cathedral

The Spanish painter and sculptor Joan Miró (1893-1983) gained international renown by peering into the subconscious mind, creating artworks that appear almost childlike. He also became famous for his contempt of conventional painting methods, which he believed “was used as a way to promote propaganda and cultural identity among the wealthy.” Miró was particularly hostile towards Cubism, famously stating, “I will break their guitar” in reference to Picasso’s painting. The content found in many of his paintings are recognizable objects, but arranged in a surrealist and bizarre manner. Miró never considered himself a surrealist, but the viewer could easily be looking at the painting within a dream. “In my pictures,” Miró writes, “I place tiny forms in huge empty spaces. Empty spaces, empty horizons, and empty plains – everything which is bare has always greatly impressed me.” His canvases are marvels of randomness, as he wanted to express inspiration from the deepest part of his mind. His “Dancer hearing an organ playing in a Gothic cathedral” was possibly inspired by the sounds of the great organ in the Gothic Roman Catholic cathedral located in his adopted home of Palma, Mallorca.

José Cabanilles: Batalla Imperial

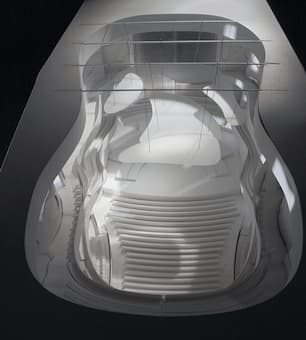

Wolf Prix: House of Music

The architect Wolf D. Prix is counted among the originators of the deconstructivist architecture movement. “Architecture,” he explains, “is art which reflects and gives a mirror image of the variety and vivacity, tension and complexity of our cities.” Prix is searching for extreme contrasts, and for him “architecture isn’t frozen music—Music is the driving force behind.” And such is certainly the case with The House of Music, designed in 2008 for the city of Aalborg, Denmark. Wolf Prix is considered one of the masters of the architectural solid, a concept he took over from music, and specifically from Beethoven. In his concertos the soloist is set against the entire orchestra, and in Beethoven’s signature trope, a loud flourish is often followed by absolute silence.

Wolf Prix: House of Music

That absolute silence becomes an emphatic void that is translated into an architectural solid. The positive figural void is part of most Prix designs, as his large public spaces have a “highly sculptured figure absorbed into and yet contrasted with a background massing.” In the “House of Music,” the central swoosh, like a Beethoven flourish contrasts with a counterpoint of the flat lines above. “I want to build string sound,” Prix explains, “and the rhetorical flourish recurs in his work in the form of a sliding glissando. It sweeps over every material and form, blending them to keep a unified experience, while counter themes erupt here and there.” Shapes, geometries and materials morph together and in essence amount to chord progressions in space.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 3, Op. 37