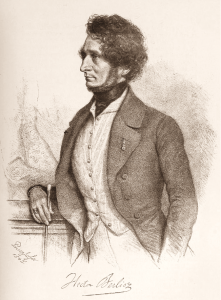

Hector Berlioz by August Prinzhofer (1845)

Harriet Smithson by Claude-Marie Dubufe (1830)

In 1831, he wrote a review of Bellini’s opera I Capuleti e I Montecchi, based on Shakespeare’s play, and in the review, outlined how he would approach the music: “it would feature the sword fight, a concert of love, Mercutio’s piquant buffooning, the terrible catastrophe, and the solemn oath of the two rival families.”

Harriet Smithson as Juliet

As Berlioz was usually torn between his reviewing and his composition, the former funding the latter, time was difficult to set aside on the work. The virtuoso violinist Niccolò Paganini gave an extraordinary gift of 20,000 francs (approx. US$100,000 in today’s money) to Berlioz after hearing Berlioz’ Harold en Italie in 1838. With this money, Berlioz could pay his debts and set to work on Romeo and Juliet. Paganini died before the work was finished and Berlioz dedicated the work to his memory.

Niccolò Paganini by Ingres

Berlioz: Romeo and Juliet, Op. 17: I. Introduction (South West German Radio Symphony Orchestra, Baden-Baden; Sylvain Cambreling, cond.)

The Prologue introduces the choir and soloists, who tell the backstory of the Montagues and the Capulets. As Shakespeare put it:

Two households, both alike in dignity,

In fair Verona, where we lay our scene,

From ancient grudge break to new mutiny…

The French text used by Berlioz was written by Émile Deschamps, a noted French poet who also wrote, with Eugene Scribe, the librettos for Meyerbeer’s Les Huguenots (1836) and Le prophète (1849).

Berlioz: Romeo and Juliet, Op. 17: II. Prologue: Choral Recitative (Europe Choir Academy, soloists, South West German Radio Symphony Orchestra, Baden-Baden; Sylvain Cambreling, cond.)

And so the symphonie dramatique continues, dramatic moments supplied by the orchestra and explanations by the chorus. In a rather Mendelssohnian style, Berlioz includes a dream scene:

Berlioz: Romeo and Juliet, Op. 17: II. Queen Mab, or, the Dream Fairy (Scherzo) (South West German Radio Symphony Orchestra, Baden-Baden; Sylvain Cambreling, cond.)

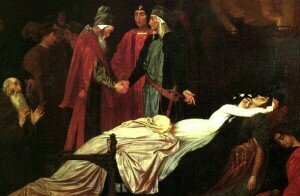

This last night of joy is followed by Juliet’s funeral procession and then the tragedy of Romeo at the vault of the Capulets.

Berlioz: Romeo and Juliet, Op. 17: III. Romeo at the vault of the Capulets (South West German Radio Symphony Orchestra, Baden-Baden; Sylvain Cambreling, cond.)

The musical setting of the dual death scene was very influenced by the version of Romeo and Juliet that Berlioz had seen in 1827: it had been rewritten by David Garrick to have Juliet awaken before Romeo’s death to increase the pathos of the scene.

The finale has also been expanded so that the families’ reconciliation is more than just the few lines in Shakespeare – the chorus makes it into a substantial finale, on a level with Beethoven’s earlier model.

Lord Leighton Frederic: The Reconciliation of the Montagues and Capulets Over the Dead Bodies of Romeo and Juliet (1853-55)

In creating the new symphonie dramtique, Berlioz enabled the composers who followed him a greater freedom in considering the forces of the symphony. Composers of the 20th and 21st century from Gustav Mahler to Tan Dun have taken up Berlioz’ model and made their own contribution to it.