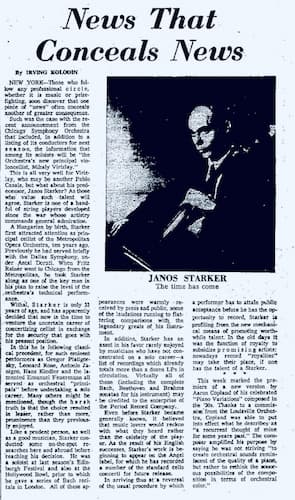

János Starker © CSO archives

Perhaps some of you don’t know that the great cellist and pedagogue János Starker began his illustrious career as an orchestral musician. He played in Broadway orchestras too.

Born in Budapest July 5, 1924, as a wunderkind, Starker performed all over Europe in the 1930s. Caught up in the tumult of World War II and the Holocaust, he was imprisoned by the Nazis in a forced labor camp. His two older brothers lost their lives. After the war Starker worked briefly as an electrician and sulfur miner to make a living, while also trying to re-establish himself as a giant of cello playing. By 1948 he’d won the Grand Prix du Disque for his recording of the Kodály Solo Sonata Op. 8, which he’d recorded in Paris in 1947.

Zoltán Kodály: Sonata for Solo Cello, Op. 8 – I. Allegro maestoso ma appassionato (János Starker, cello)

Starker immigrated to the United States with the help of Antal Dorati then the conductor of the Dallas Symphony. Starker became principal cello of the Dallas Symphony 1948-49, followed by the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, (The MET) from 1949-53, and then the great maestro Fritz Reiner lured him to the Chicago Symphony where Starker played as principal from 1953-58.

Johannes Brahms: Piano Concerto No. 2 in B-Flat Major, Op. 83 – III. Andante (Emil Gilels, piano; Chicago Symphony Orchestra; Fritz Reiner, cond.)

© CSO archives

When Starker decided to leave his position, he recommended fellow Hungarian Mihály Virizláy as his replacement. Unbeknownst to Reiner, Virizláy had been a student of Starker and a child prodigy in Hungary somewhat like himself. Virizlay also gained wide recognition but he was forced to flee during the 1956 Hungarian revolution with only a few hundred dollars in his pocket. He became a refugee and was interned at Camp Kilmer, NJ with other Hungarian refugees. Starker helped Virizláy out of the internment camp and found him a job at the Dallas Symphony. Reiner voiced his doubts. He asked Starker if Virizláy was good enough for the CSO. Starker replied that Virizláy was a terrific cellist but perhaps not experienced as an orchestral player as Reiner might like.

Reiner, incensed that Starker was leaving the orchestra, telephoned Starker to tell him that Virizláy had been engaged. Reiner followed up with a devious question, “Why did you say he wasn’t very good?” Which of course is not what Starker had said. The Chicago audience members found out in a more covert way. Hidden in a newspaper article entitled “News that Conceals News” which announced the soloists for the following CSO season, Virizláy’s name appeared in print as the new principal cello. As you can hear in the William Tell Overture by Rossini he was a great cellist.

Gioachino Rossini: Guillaume Tell (William Tell): Overture (Chicago Symphony Orchestra; Fritz Reiner, cond.)

János Starker, Fritz Reiner and new musicians © CSO archives

Virizláy must have had a very harsh probationary period. Starker after all, was a tough act to follow! Sure enough, Virizláy stayed only one year with the Chicago Symphony (1958-59) Virizláy’s tenure with the Baltimore Symphony as principal cello began in 1962, after serving as Pittsburgh assistant principal. He performed with the BSO for four decades and became a noted composer. Frank Miller succeeded Virizláy and remained for 25 seasons.

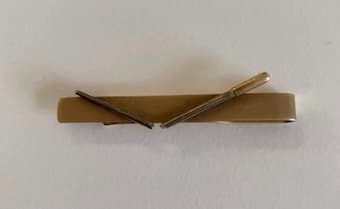

During one of Starker’s last rehearsals with the Chicago Symphony his mind unexpectedly drifted off during a passage for unaccompanied sopranos in a choral work—one of the several sections of rests of more than 30 bars. We all can sympathize. Starker abruptly woke up and he came in, really loudly, fff but one bar too soon, all by himself! Everyone else counted the measures of silence. His colleagues burst out laughing but Reiner glared furiously at Starker. Throwing his baton to the floor with vehemence, he screamed, “Why can’t some people just watch!” The baton landed on the floor and broke in two. Starker responded in his terse, quiet way, after all it was the first mistake of Starker’s CSO tenure, “am I not entitled to one mistake? I am sorry.” Although Starker and Reiner were as close to one another as anyone in the orchestra, quite a bit of time had to pass before the two made up. One never talked back to the great maestro! This story became legendary among the musicians. As a parting gift the CSO cello section gave Starker a gold tie pin shaped like a broken baton.

In 1958, after leaving the CSO, Starker went to Indiana University for one year as artist in residence to see how it might work out. Appointed full professor the following year, in 1962 he became distinguished professor and remained at IU (now the Jacobs School of Music) in Bloomington, Indiana until his death in 2013. He is known for an incredible and versatile discography including less often played works such as the lovely Hovhaness Cello Concerto.

Alan Hovhaness: Concerto for Cello and Orchestra, Op. 17 – Andante – Maestoso (János Starker, cello; Seattle Symphony Orchestra; Dennis Russell Davies, cond.)

Starker’s gold tie-clip© Gwen Starker

Starker looked upon his time in Chicago as invaluable. He would often say to his students, “playing with Reiner you learned something new every day.” As an orchestral musician for eleven years Starker encountered some of the greatest conductors, soloists, and opera stars of the 20th century. He emulated the great musicians he heard and from this inspiration he honed his distinctive cello sound, exemplary approach, impeccable musicality, and the simplicity, purity, and balance with which he played.

Starker often wore the souvenir of his CSO days. The gold tie pin given to him reminded Starker of the wonderful experiences playing under Fritz Reiner.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Sometime after I joined the CSO cello section in 1974 Starker came back as a soloist. He was wearing that tie clip at the rehearsals.

One small point: Reiner didn’t exactly lure Starker to Chicago…he took the great cellist with him when he left his post as music director of the Metropolitan to assume the Chicago position.

I remember greeting Janos after a concert and he told me he was dead tired after flying all night and not getting any sleep. I was shocked because he had performed so brilliantly during the recital.