If Joao Carlos Martins’s life has been pretty eventful, as I mentioned in my last article, the same can be said of his music, and the hallmark of his piano playing as well as of his conducting work is his genius originality. From the beginning of his career, Martins has imprinted his personal style on music of the compositions (often played ad nauseam) by great masters such as Bach, Schumann or Mozart. Despite having been sometimes criticised by his inventive approach to these well-known composers, Martins has remained true to his vision that great pianists are those that let their real selves come to the surface in music. In another excellent documentary about his life, Reverie (Johan Kennive and Tim Heirman: 2006), he says that “surely the point of interpretation is playing like yourself (….) somebody who played the notes exactly as they are written would be a computer!”. Furthermore, he mentions that even composers like Benjamin Britten, who obsessively annotated their scores leave a lot out, that must be intuited by the player. This feeling for the music is the mark of a great player.

If Joao Carlos Martins’s life has been pretty eventful, as I mentioned in my last article, the same can be said of his music, and the hallmark of his piano playing as well as of his conducting work is his genius originality. From the beginning of his career, Martins has imprinted his personal style on music of the compositions (often played ad nauseam) by great masters such as Bach, Schumann or Mozart. Despite having been sometimes criticised by his inventive approach to these well-known composers, Martins has remained true to his vision that great pianists are those that let their real selves come to the surface in music. In another excellent documentary about his life, Reverie (Johan Kennive and Tim Heirman: 2006), he says that “surely the point of interpretation is playing like yourself (….) somebody who played the notes exactly as they are written would be a computer!”. Furthermore, he mentions that even composers like Benjamin Britten, who obsessively annotated their scores leave a lot out, that must be intuited by the player. This feeling for the music is the mark of a great player.

In a recent article (‘Virtuoso young pianist? Get in line’ 13/8/2011), Anthony Tommasini, the chief musical critic of The New York Times, comments that with so many outstanding young musicians with perfect technique emerging, it is hard to tell the truly inspired ones from the “mere” technical geniuses. He suggests dividing pianists – even the truly inspired ones – into two basic groups: “those who have the technique to play anything and those who have all the technique they need, thank you, to play the music that is meaningful to them”. In the former group he would include pianists such as Lang Lang, Garrick Ohlsson and Martha Argerich; in the latter, Andras Schiff, Mitsuko Uchida, Richard Goode.

There is no doubt that Martins would include himself in the second group. His relationship with the music he plays is almost mystical. From the belief that Bach has saved him during the many low points of his life to his wholehearted devotion to his Bachian Orchestra Foundation, through which he sponsors scholarships for poor students, Martins sees playing not only as a technical job, but as a means of personal expression. It would not make sense, therefore, to play music that is not meaningful to him. One could counter-argue, of course, that this attitude can only be adopted by an established artist, who can afford to just express himself, who no longer needs to prove himself with virtuoso demonstrations. But is it not the personal link that makes one particular concert so special? The understanding of how much of the artist is being laid bare in front of our eyes and ears on that stage? This is what I felt in a concert by Trevor Pinnock in July, which I wrote about a few weeks ago.

In The Concept of Anxiety, Kierkegaard writes that “the originality of the self (“Gemuth”)… when it is acquired and cultivated, leads to the successive and to repetition, but when there is no originality in the repetition, it is nothing more than habit. The serious man is serious precisely because of the originality with which he repeats himself in repetition”. Although this idea that repetition is not habit, but rather an exercise in originality, may seem paradoxical, but what he means is that true Repetition can only be the repetition of oneself. It is only when one becomes truly oneself that one can be that same person day after day. If one is not repeating oneself, he says, “it is mere pedantry”. With originality, one remains in love, interested and animated.

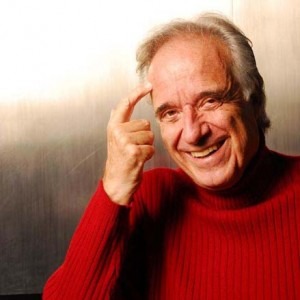

Martins is anything but a pedant. He expresses himself through music in a profound sense. If before I have covered his Life, there is no doubt that music is his Passion.

Ps. A wonderful example of Martins’s thoughts on music (from an interview with Raymond Tuttle in Fanfare);

“Consider the relationship between Bach’s brain and his heart. In my opinion, his brain was polyphonic and his heart monophonic. Why do I say that? When you hear Bach’s many emotional states – pain, love, romanticism, lyricism, virtuosity, a pastoral kind of attitude – you hear a monophonic soprano voice singing over a basso continuo. His most

important melodies came from the heart. When you get to Bach the scholar – the man who wrote the fugues – then you hear Bach’s brain. But even in his fugues, his subconscious was still monophonic; his heart was still occupied with a soprano line and a continuo. So, when I am playing one of Bach’s fugues, what statement am I trying to make? I try to show all the polyphonic intricacy of the subjects and the countersubjects, but I never play the subject exactly the same way every time that it occurs. Instead, I try to play it differently; I vary it, because its context within the piece is always changing. Everything I do, I do with purpose, although it may be disturbing to some people.”

Martins talking about The Well-Tempered Clavier, with his amazing playing: