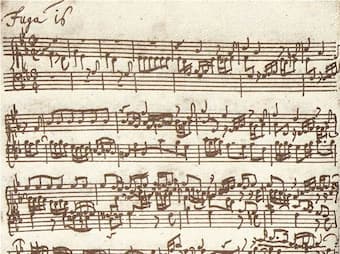

Schübler Chorales

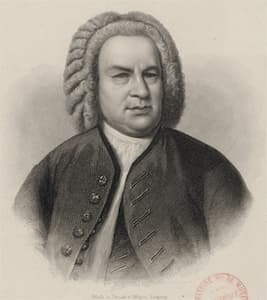

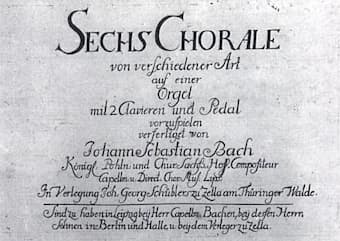

Johann Georg Schübler (1720-1755?) was an engraver and organist, and a private student of J.S. Bach. “He learned the music in Leipzig with the famous Bach,” but Schübler’s name is more notably connected with the publication of a set of chorale preludes composed by Bach. Commonly known as the “Schübler Chorales” BWV 645-650, the engraver issued the compilation between 1747 and 1748. At least five preludes are transcriptions from movements in Bach’s church cantatas, and the composer might have hoped to provide an approachable version of the music through the marketable medium of keyboard transcriptions. Since virtually all Bach cantatas were unpublished in his lifetime, Bach was possibly looking to make a significant public statement. It almost seems that Bach himself issued his “Greatest Hits.” Be that as it may, the fact that Bach had gone to the trouble and expense of securing the services of a master engraver to produce this collection clearly indicates that he did regard the “Schübler Chorales” as a significant publication.

Johann Sebastian Bach: “Schübler Chorales” BWV 645-650 (Norbert Pétry, Organ)

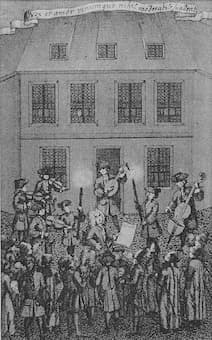

Collegium Musicum in Leipzig

Georg Balthasar Schott (1686-1736) took over the direction of the Collegium Musicum in Leipzig in 1718. G.P. Telemann had founded the collegium in 1702 as a voluntary association of professional musicians and university students. Focusing on performances of instrumental music, they met twice weekly to provide music for church, state and academic occasions. Schott worked closely with Bach, who frequently featured as guest-conductor and soloist. When Schott was appointed Kantor at Gotha in March 1729, Bach was quickly appointed his successor. Since the society played an important part in the flowering of bourgeois musical culture, Bach took full advantage of this new opportunity. For six year, Bach had practically written nothing but sacred music; now he was able to provide the ensemble with a steady stream of original instrumental compositions. Unfortunately, the official programmes of these weekly concerts did not survive, but we do have original performing parts for such works as the glorious Orchestral Suites, BWV 1066-1068.

Johann Sebastian Bach: Orchestral Suite No. 2 in B minor, BWV 1067

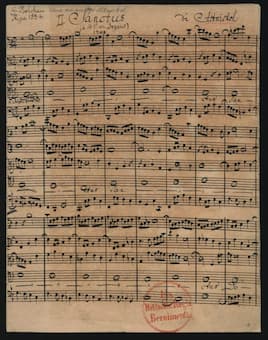

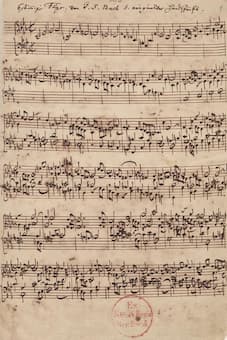

Johann Christoph Altnickol’s handwriting

Today we barely remember the name of the organist and composer Johann Christoph Altnickol (1720-1759). His compositions did not attract much attention, but his music was highly praised by J.S. Bach. There might be a couple of reasons for that. For one, Altnikol was Bach’s son in law, as he married Elisabeth Juliana Friederica Bach in January 1749. Altnickol had been employed as a singer and assistant organist in Breslau, before studying theology at the University of Leipzig from March 1744. He quickly became a private student of Bach in composition and keyboard instruments, and he sang as a bass in Bach’s choirs.

Bach: Well-Tempered Clavier Part 2

Altnickol also worked as a copyist for his soon to be father-in-law, and in 1744 he produced a fair copy of the newly completed and revised Well-Tempered Clavier Part 2 (BWV 870-893). Other important Bach copies in Altnickol’s hand include the Violin Sonatas (BWV 1014-1019), the French Suites (BWV 812-817), and the St Matthew Passion (BWV 244). According to an important eyewitness biographer, Bach dictated his last chorale prelude to Altnickol on his deathbed, but that manuscript did not survive.

Johann Sebastian Bach: The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 2 (BWV 870-893) (Evgeni Koroliov, piano)

Bach concert hall at the castle at Köthen

The scientist and poet Salomo Franck (1659-1725) was working at Weimar at the same time as Johann Sebastian Bach. A native of Weimar, Franck studied law and theology and eventually was in charge of the library records for the court of William Ernest, Duke of Saxe-Weimar. Franck had written a number of secular cantata texts before his association with Bach, and in his sacred texts he preferred to alternate verses from the Bible with strophic songs. His poetry was of sufficiently high standards, and Franck gradually started to adopt new poetic principles for his cantata texts by integrating da capo arias and recitatives into his poetry. When Bach was promoted to the post of Konzertmeister at Weimar in 1714, he was responsible for the composition and performance of cantatas for the court chapel on a regular monthly basis. Bach and Franck collaborated on a number of projects, and although Bach would eventually depart Weimar, he still continued to engage with Franck’s poetry. During his time in Leipzig, Bach partly enlarged existing cantatas, as for example BWV 70 and BWV 80, or he composed new ones, including BWV 168.

Johann Sebastian Bach: Tue Rechnung, Donnerwort, BWV 168

Dietrich Buxtehude

In 1705, a young and ambitious composer set out from the city of Arnstadt to walk to the city of Lübeck, a journey of almost 400 kilometers. That ambitious young composer was Johann Sebastian Bach, who had just landed his first professional post as church organist in Arnstadt in 1703. The reason for his long walk was to hear one of the most famous composers and organists, Dietrich Buxtehude. Buxtehude was organist at St Mary’s Church, one of the most coveted musical positions in the land. In addition, Lübeck was a free imperial city and enjoyed a culturally liberal atmosphere that afforded a number of important freedoms to musicians. Buxtehude traveled frequently; he had a private studio and was able to develop his skills as a keyboard virtuoso while juggling his official duties as town organist. Bach had applied for permission to leave his post for a month to hear Buxtehude. In the event he ended up staying four months, and Buxtehude may even have offered Bach his daughter’s hand in marriage. History tells us that Bach did not marry Buxtehude’s daughter—neither did Handel by the way—but he carried back a substantial number of manuscript copies of Buxtehude’s work.

Johann Sebastian Bach: Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor, BWV 582

Prince Leopold of Cöthen

During his professional career, Bach was probably happiest in the service of Prince Leopold of Cöthen. Bach met the Prince in 1716, and Leopold lost no time in offering him the job of Kapellmeister. Bach was overjoyed and signed his contract on 7 August 1717, but there was trouble with his current employer Duke William Ernest of Saxe-Weimar. He accused Bach of not following correct procedures in requesting his release, and he imprisoned the composer from 6 November to 2 December 1717. Prince Leopold was a young man who loved and understood music. His father had died early on, and young Leopold persuaded his mother to engage a small musical ensemble and establish a court orchestra. Leopold was a capable singing bass, and he also played the violin, viola da gamba and harpsichord. Bach received a substantial salary, only one court official was paid more, and there is other evidence that Bach was held in high esteem. They also enjoyed a good personal relationship, as Prince Leopold became godfather for Bach’s son Leopold Augustus. That happy relationship did not last, however, as Prince Leopold married his cousin Friederica, Princess of Anhalt-Bernburg. The princess was not interested in music at all, and increasingly jealous of the happy friendship between her husband and Bach. Eventually, Bach departed for Leipzig, but during his time in Cöthen he composed a substantial number of his most famous secular and instrumental works.

Johann Sebastian Bach: Cello Suite No. 1

Erdmann Neumeister

The theologian and librettist Erdmann Neumeister (1671-1756) was highly influential in the development of church cantata texts. In his first cantata texts, he combined biblical verses, strophic arias, and the occasional chorale strophes. In his later cycles published in 1711 and 1714, Neumeister inserted biblical texts—recitative and arias—and chorales into his cantatas, thus mixing the forms of traditional German church music with those of contemporary Italian opera. Scholars generally agree that Neumeister was not the inventor of “this type of cantata text, but highly important in the further development of Protestant church music.” Neumeister was in Hamburg when Bach applied for a position as organist at St. James. He strongly supported Bach’s appointment, but ultimately, the position was given to a man who gave a large donation to the church. Neumeister commented with outrage that the church would reject even “one of the angels of Bethlehem … who played divinely,” if that angel could not produce enough money. Ultimately, Bach composed music for at least five of Neumeister’s libretti, and “the two men continued to share a Lutheran understanding of piety as the natural fruit of the proclamation of the gospel.”

Johann Sebastian Bach: Wer mich liebet, der wird mein Wort halten,” BWV 59

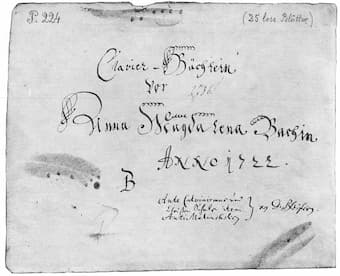

Title page of a collection of strophic songs by Johann Sebastian and Anna Magdalena Bach

We know that Johann Sebastian Bach was married twice. His first wife Maria Barbara died tragically in 1720, after thirteen years of marriage. We are still unsure when Bach first met the singer Anna Magdalena Wilken, but in September 1721 she was at Köthen and well acquainted with Bach. She was just 20 years of age and Bach was 36, but they were ready to be married. Bach paid two visits to the city cellars to buy small barrels of Rhine wine, and the happy marriage took place on 3 December 1721.

Anna Magdalena Bach notebook

Over the years, Anna Magdalena Bach fulfilled many different roles. Above all, she mothered a large and steadily increasing family. When she married the widower Bach, she took on four small children, and subsequently gave birth to thirteen children over nineteen years, averaging one a year for most of that span. Their shared interest in music surely contributed to their happy marriage. Anna Magdalena continued to sing professionally after her marriage, and she organized regular musical evening featuring the entire family playing and singing together with friends. And while she was an invaluable aid in coping and transcribing her husband’s music, she almost certainly did not compose any of it.

Johann Sebastian Bach: Clavierbüchlein for Anna Magdalena Bach, Book 2, BWV Anh. 113-132 (excerpts) (Nicholas McGegan, harpsichord)

Johann Sebastian Bach: Clavierbüchlein for Anna Magdalena Bach, Book 2, BWV Anh. 113-132 (excerpts) (Nicholas McGegan, harpsichord)

Johann Nikolaus Forkel

In the wider sense of the term, Johann Nikolaus Forkel (1749-1818) was a definite friend of J.S. Bach. Forkel was a musicologist and music theorist, and an enthusiastic admirer of Bach and his music. He wrote his first biography of Bach in 1802, and it became a most valuable document since he was still able to correspond directly with Bach’s sons C.P.E. Bach and Wilhelm Friedemann Bach. Most importantly, however, Forkel elevated the study of music history and theory to an academic discipline, which adhered to the rigorous standards of scholarship. Of particular interest is Forkel’s discussion of Bach’s success as a teacher. Forkel writes, “Bach was a good teacher because he took great pains to learn and develop his own knowledge and talent, and he was unafraid to drill excessively.” Furthermore, “he led by example; rather than throwing a student into the deep end and letting him figure things out on his own, Bach took time to demonstrate superior musicianship.” And finally, Bach introduced students to good material. “As long as his pupils were under his instruction Bach did not allow them to study any but his own works and the classics. The critical sense, which permits a student to distinguish good from bad, develops later than the aesthetic faculty and may be blunted and even destroyed by frequent contact with bad music. The best way to instruct youth is to accustom it early to consort with the best models.”

Johann Sebastian Bach: Trio Sonata No. 3 in D minor, BWV 527

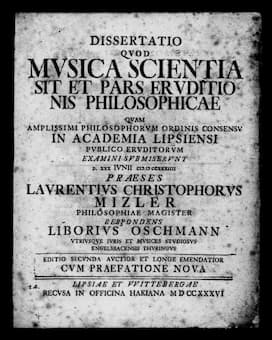

Lorenz Christoph Mizler’s dissertation

Lorenz Christoph Mizler (1711-1778) founded the “Corresponding Society of the Musical Sciences” in 1738. The aim of the society was to enable musical scholar to circulate theoretical papers in order to further musical science by “encouraging discussion of the papers via correspondence.” Membership in this society was limited to twenty members, and it involved the submission of “a scientific work.” Mizler counted J.S. Bach among his “teachers” and he reports that he learned composition “among other things by dealing with the conductor Bach.” His 1734 dissertation was dedicated to Bach and he described him “as a friend and a patron.”

Bach: Musical Offering

Mizler urged Bach to join his society, and although Bach was initially hesitant, he did submit his canonic composition “Vom Himmel hoch,” BWV 769 in 1747. Once he had been accepted, Bach took no further interest in the society’s affairs. According to his son C.P.E. Bach, “he thought nothing of the dry, mathematical stuff Mizler wanted to discuss.” Regardless, in 1748, Bach sent the society his “Musical Offering” BWV 1079, and probably planned to submit “The Art of the Fugue” in lieu of a scientific dissertation in the year thereafter.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Johann Sebastian Bach: Musical Offering, BWV 1079 (Konstantin Lifschitz, piano)