Johannes Brahms

Johannes Brahms was well connected. He befriended and collaborated with hundreds of people during his career, including fellow musicians and composers, publishers and artists, poets whose texts he set to music, and even rulers of certain German states with whom he had significant contact. Since Brahms was a prolific writer of letters, and generally not shy in expressing his opinion, we are able to gain significant insight into his character, life and career.

Adolf Schubring (1817-1893) was a learned man who mastered a number of languages including Sanskrit, Greek, Latin, and Hebrew. But he was also a competent pianist and an eager music critic. He was the first critic to give his assessment of Brahms’s early compositions, and the one he valued most highly was the String Sextet Op. 18. Schubring described it as “the loveliest, most beautiful, and most mature.” Schubring and Brahms engaged in an extended correspondence, which assumed a personal and friendly tone from the onset. For one reason or another contact between the two men ceased after 1886, and Richard Schubring wrote “For my father, the sun of his life set when he lost contact with Brahms.”

Johannes Brahms: String Sextet No. 1, Op. 18 (Berlin Philharmonic Octet)

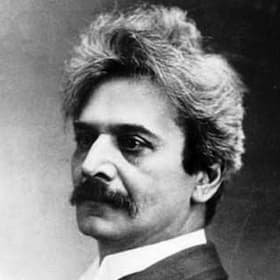

Paul Heyse

Paul Heyse (1830-1914) was a poet, dramatist and novelist and awarded the Nobel Prize for literature in 1910. Brahms set 12 of his texts to music, with the dates of their composition ranging from 1852 to 1886. Brahms discovered Heyse early in life, and he was certainly eager to meet him in Munich. He presented himself at Heyse’s house in 1864, 1869, and 1870, but Heyse was away each time. Finally, in May 1873 the two men met and Brahms was immediately charmed by his personality. He writes to Max Kalbeck, “Heyse knew how to animate and liven up the atmosphere in a room—as soon as he entered it, one felt that the sun was suddenly shining into it.” The contact between Heyse and Brahms remained steady, and interestingly, Heyse discussed with Brahms the possibility of an opera. Heyse even produced the outline of a libretto on a celebrated medieval French knight “Ritter Bayard,” but Brahms was not really interested.

Johannes Brahms: 5 Lieder, Op. 107, No 5 “Mädchenlied” (Erika Köth, soprano; Peter Backhaus, piano)

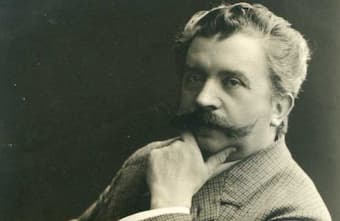

Julius Röntgen

The composer and pianist Julius Röntgen (1855-1932) did not immediately warm to the music of Brahms. They properly met in Leipzig in 1877 as Brahms was conducting his First Symphony. At a musical soiree at that time, Röntgen played Brahms chamber music in the presence of the composer. Brahms immediately took a great liking to him, but it was during Brahms’s visits to Holland that they get to know each other well. Röntgen played the Second Piano Concerto under Brahms’ direction, and the pianist started to feel increasing admiration for both the man and his music. In fact, Röntgen became a fervent admirer of Brahms’s music. They continued to meet repeatedly, and while Röntgen’s attitude towards Brahms was “solely one of passive reverence,” Brahms expressed his feeling with unusual warmth. As he writes to Clara, “Röntgen is a quite exceptional and most lovable man. He has remained a child, so innocent, pure, frank, and enthusiastic. Not for a long time have I taken such great pleasure in anyone.” Brahms even thought favorably of Röntgen’s compositions, characterizing his talents as “light and pleasing.”

Johannes Brahms: Piano Concerto No. 2, Op. 83 (Konstantin Lifschitz, piano; Konzerthausorchester Berlin; Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, cond.)

Hans Richter

The conductor Hans Richter (1843-1916) was a devoted follower of Richard Wagner. In fact, he had conducted the first full Ring cycle at Bayreuth in 1876. In addition, he was a stout champion of the music of Anton Brucker. However, he also directed many performances of Brahms’s orchestral and choral works, including a number of world premieres. Richter and Brahms collaborated on the first Viennese performance of the Second Piano Concerto, and he was responsible for the acceptance and growing popularity of Brahms’s music in England. He conducted numerous concerts in London and was music director for the Birmingham Festival. A reviewer wrote, “The fact that Brahms’s symphonies are listened to and loved by the few, and tolerated at all by the many is due, like so much else of what is good in English musical taste, very largely to the efforts of Hans Richter.” And it was Richter who directed the first English performance of Gesang der Parzen on 5 May 1885.

Johannes Brahms: Gesang der Parzen, Op. 89 (Berlin Radio Choir; Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra; Claudio Abbado, cond.)

David Popper

The cellist and composer David Popper (1843-1913) initially studied at the Prague conservatory and made highly successful concert appearances in Germany and subsequently Holland, Switzerland and England. He first appeared in Vienna in 1867, and he occupied the post of principal cellist at the Vienna opera. He continued to travel the world but eventually settled in Budapest and became a founding member of the Hubay Quartet. As a member of that quartet, he predictably played in numerous performances of Brahms’ music. And that included first public performances of the Piano Trio op. 101, and the new and revised version of the Piano Trio op. 8. Brahms took part in both performances, and complimented Popper’s playing. Popper also composed a number of works for cello, including several concertos and shorter compositions for cello and piano. Apparently, he liked to show his compositions to Brahms, who was regrettably not greatly impressed.

Johannes Brahms: Piano Trio No. 1, Op. 8 (1890 version) (The Kalichstein-Laredo-Robinson Trio)

Gottfried Keller

The Swiss poet, novelist and short story writer Gottfried Keller (1819-1890) first met Brahms in 1866, and then got to know him much better during the composer’s stay on Lake Zurich in the summer of 1874. On one occasion, Keller sent Brahms a humorous text he had written for a friend’s wedding, and asked him to set it as a wedding cantata. Brahms obliged with little enthusiasm, as he “did not consider the words very suitable for a setting to music, nor indeed for the occasion.” However, Brahms greatly admired Keller as a writer and poet, and he did set three of his poems to music. Upon Keller’s death, Brahms was given access to letters Keller had written to family and friends, and he found them so entertaining that he copied many passages for his personal pleasure. It has been reported that he even spent an entire afternoon reading many of them to his biographer Max Kalbeck.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Johannes Brahms: 4 Gesänge, Op. 70, No. 4 “Abendregen” (Janina Baechle, mezzo-soprano; Markus Hadulla, piano)

Excellent overview. The last word on Brahms has still not been told