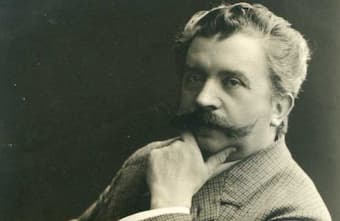

Fritz Steinbach

Fritz Steinbach (1855-1916), none withstanding Hans von Bülow, was regarded as the foremost conductor of Brahms’ music. We know that they first met when Steinbach attempted to persuade Brahms to take him on as a student in 1875. Brahms declined, and advised him to study with Nottebohm and Door in Vienna. In the event, Brahms had a high opinion of Steinbach’s musicianship, and he recommended Steinbach to Duke Georg II for the position of music director at Meiningen. Steinbach immediately made Brahms the center of his musical activities, and conducted all symphonies in the presence of the composer. Apparently, Brahms was so moved by his interpretation of the First Symphony that he asked for a repeat performance. Steinbach also organized the famous “three B’s” festival in Meiningen, and Brahms reports, “You can’t imagine how wonderful it is to do music here. The chorus, the orchestra and that incomparable Steinbach; everything is perfection.” Steinbach continued to strongly promote Brahms’ music, and he made a special trip to Vienna to see his dying friend in 1897.

Johannes Brahms: Symphony No. 1, Op. 68 (London Philharmonic Orchestra; Marin Alsop, cond.)

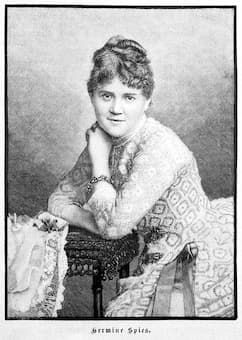

Hermine Spies

Hermine Spies (1857-1893) was a high-spirited woman, “whose pleasing manner and attractive looks greatly enhanced her beguiling effect produced by her voice.” She first met Brahms in 1883 under dramatic circumstances. Hermine, so it is told in an anecdote, fled from the hall in tears during a public rehearsal after being reprimanded for a mistake by the conductor Ferdinand Hiller. It was reported that Brahms consoled her, and led her back to the podium. In the event, she sang in a performance of the Alto Rhapsody in Koblenz, and wrote, “To sing under Brahms is marvelous. He has such a calming effect on the singer.” In turn, Brahms formed a high opinion of her as an artist, and he would see much more of Hermine in the coming years. This prompting some gossip that he was intending to marry her. When Hermine heard the news, she was filled with dismay. “You are mistaken,” she writes to Maria Fellinger, “in what you write about Brahms in relation to myself… No doubt he quite likes me, for I sing his songs no worse than other and I am also, after all, a creature equipped with five healthy senses. But that he belongs to me, I absolutely refuse to accept that responsibility.”

Johannes Brahms: Alto Rhapsody, Op. 53 (Stephanie Blythe, mezzo-soprano; Ensemble Orchestral de Paris; John Nelson, cond.)

Richard Mühlfeld

Richard Wagner personally recruited Richard Mühlfeld (1856-1907) for his Bayreuth Festival in 1875. But surprisingly, Mühlfeld at that time was a violinist, and only switched to the clarinet in 1876. He made his first appearance as a clarinet soloist at the Meiningen Orchestra, and he quickly gained an international reputation. A London critic wrote, “Herr Mühlfeld is a superlatively fine artist, and not only his tone, but the perfect of his phrasing, the depth of this musical expression, and his absolute ease and finish mark him as a player altogether without parallel.” Brahms heard Mühlfeld in concert on numerous occasions, but it took him until 1891 before he truly appreciated the exceptional quality of Mühlfeld’s playing and composed four of his last works for him. Brahms write, “Mühlfeld is the greatest master of the instrument, and I cannot imagine a performance of these compositions by anybody else.”

Johannes Brahms: Clarinet Sonata, Op. 120, No. 2 (Karl Leister, clarinet; Gerhard Oppitz, piano)

Robert Hausmann and Brahms

The cellist Robert Hausmann (1852-1909) had a distinguished career, both as a soloist and as a chamber musician. Max Kalbeck wrote about him in his Brahms biography, “Whoever saw him was bound to trust him unconditionally, and whoever heard him play fell completely under his spell.” He was first introduced to Brahms in 1872 and remarked, “I greatly prefer the music to the man.” Over the years Hausmann gradually came to appreciate Brahms the man, and he inspired the composer to craft at least two major works, the Cello Sonata op. 99 and the Double Concerto. They performed together on numerous occasions, and Brahms wrote to Eduard Hanslick, “If Herr Hausmann from Berlin should pay you a visit in the near future, do receive him. You will derive pleasure from the young man in every respect, even without his excellent cello playing.

Johannes Brahms: Double Concerto for Violin and Cello, Op. 102 (Itzhak Perlman, violin; Mstislav Rostropovich, cello; Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra; Bernard Haitink, cond.)

Bettina von Arnim

An early feminist and advocate of social reforms, Bettina von Arnim (1785-1859) was a friend of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and of Beethoven. One of the most celebrated and flamboyant figures of the German Romantic movement, Bettina was the wife of the poet Achim von Arnim and sister of poet and novelist Clemens Brentano. Brahms met her and her daughter Gisela through Robert and Clara Schumann in October 1853. His friend Joseph Joachim was greatly attracted to Gisela, and Bettina clearly made an impression on the young Brahms, who much late in life, around 1895, wrote, “Ah yes, Bettina von Arnim, whom I still knew, now there was a woman one had to take seriously! What a brilliant mind she had.” In fact, he decided to dedicate the 6 Gesänge op. 3 to her, and Bettina returned the favor by presenting Brahms with a volume of poems by the early Romantic writer Novalis. Shortly thereafter she also send him the complete edition of her own and Achim’s works.

Johannes Brahms: 6 Gesänge, Op. 3 (Juliane Banse, soprano; Andreas Schmidt, baritone; Helmut Deutsch, piano)

Gustav Walter

According to a Brahms biographer, Gustav Walter (1834-1910) was Brahms’ favorite tenor. Walter had received instruction from Franz Vogl in Prague and made his operatic debut as Edgardo in Lucia di Lammermoor at Brünn in 1855. Shorty thereafter he was engaged at the Vienna opera and became the leading lyric tenor of the company. Contemporaries celebrated his beautiful singing of Mozart roles, but he also excelled in selected Verdi productions. In addition to his distinguished career on the operatic stage, he also shone on the concert platform and was greatly admired as an interpreter of Lieder. Brahms saw Walter in various performances, and he frequently accompanied him in public and private concerts. On one occasion, Brahms even took Walter to Budapest and performed some of his most recent songs at a concert of the Hubay Quartet. Walter also took part in the first performance of Rinaldo, and he gave the first public performances of a considerable number of Brahms songs.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Johannes Brahms: Rinaldo, Op. 50 (René Kollo, tenor; Prague Philharmonic Chorus; Czech Philharmonic Orchestra; Giuseppe Sinopoli, cond.)