“Pepi (Josef) is the more gifted of us two; I am merely the more popular…”

Josef Strauss

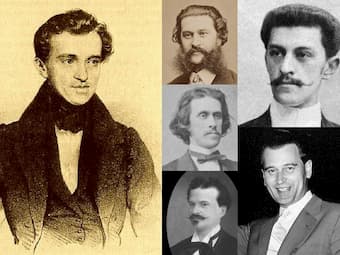

When it comes to dynasties in classical music, it’s difficult to upstage the Viennese Strauss family. They were musical megastars of international reputation whose dance music conquered much of Europe and indeed much of the world. They combined incredible musical prowess with acute business savvy that earned them astronomical amounts of money. The musical dynasty got started in earnest with Johann Strauss I, who sired three superbly talented sons; Johann II, the future waltz king was born in 1825, Eduard in 1835, and probably the all-around most talented Josef Strauss (1827-1870) was born 1827. Even the waltz king had to concede, “Josef is the more gifted, and I am simply more popular.” In fact, the world-famous “Pizzicato Polka,” was co-written by Johann II and Josef Strauss.

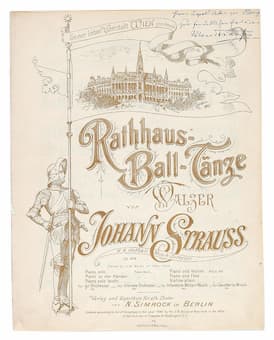

Rathaus-Ball-Tänze Waltz by Johann Strauss

Johann Strauss I was determined that his sons would not become professional musicians, but he nevertheless provided them with a rudimentary musical education. Josef was destined for a career in the Austrian military, but he defied his father’s wishes and completed courses in technical drawing and mathematics at Vienna’s Polytechnic Institute. Simultaneously he studied landscaping and ornament drawing at the Academy of Fine Arts. Josef worked happily for the city of Vienna as an engineer, architect and designer, and simultaneously he entertained his hobbies as painter, poet, dramatist, singer, composer and inventor. His mother jokingly suggested that Josef should take a position in his brother’s orchestra, but Josef simply laughed at the idea, suggesting that “he was too ugly for a career on stage.” However, when the waltz king collapsed in December 1852, with physicians suggesting that his exhaustion was life threatening, Josef was told to interrupt his technical career and join the family waltz business. Reluctantly he agreed, and he made his first appearance as an “interim director” with the Strauss Orchestra in 1853.

Josef Strauss: Die Ersten und Letzten, Walzer (The First and the Last) Op. 1 (Slovak State Philharmonic Orchestra, Košice; Christian Pollack, cond.)

The Strauss dynasty

On that premiere occasion, Josef composed a waltz in the style of a Ländler, and gave the work the title “The First and Last,” which basically means “Once and never again.” The audience and music critics were ecstatic, and a renowned local newspaper wrote, “Josef Strauss is a definite musical talent. It would be a pity if he were to retire so soon from public appearances. His waltzes are full of freshness and vitality, of that electricity which seems to be the sole property of the Strauss family. The thunderous applause and the never-ending encores will hopefully encourage Mr. Josef Strauss to write a new composition.” When Johann II was able to return to work, Josef intensified his musical education, took violin lessons and studied composition. Overwhelmed by the unexpected success, Josef agreed to act as an assistant at the Strauss Orchestra and he wrote another work, this time titled “The First Waltz after the Last.” However, Josef constantly fought with persistent headaches and eye problems that were diagnosed as congenital brain damage by physicians. Nevertheless, Josef undertook an extended Russian tour in 1863 and 1864, and once again in 1869, with his brother Eduard joining in the leadership of the Strauss orchestra.

Josef Strauss: Hesperus-Bahnen, Op. 279 (Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra; Franz Welser-Möst, cond.)

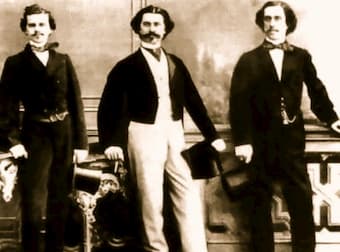

Johann Strauss II, Josef Strauss and Eduard Strauss

Josef systematically enriched the repertoire of the Strauss Orchestra by including music by Richard Wagner—including arrangements of music from Tannhäuser, Lohengrin and Tristan and Isolde, and previewing Rheingold and Die Meistersinger even before these works received their world premieres. In his own compositions, Josef evidenced superior craftsmanship, and many of his melodies sound a melancholic charm that differentiates them from the music of his father and his brothers. In April 1870, Josef gave his final concert in Vienna before travelling to Warsaw for a series of concerts. Josef collapsed on the conductor’s podium, and severely struck his head during the fall. Never regaining consciousness, Josef was returned home to Vienna where he died five days later. His wife refused an autopsy, and he was originally buried in the St Marx Cemetery. Josef’s legacy includes roughly 300 original dances and marches, and more than 500 unpublished arrangements of music by other composers. Eduard Strauss subsequently burned the vast majority of these arrangements.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter