How did Josef Strauss incorporate his life passions in his compositions?

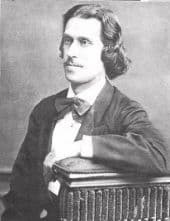

Josef Strauss

Born into one of the most famous Viennese musical families, Josef Strauss (1827-1870) really had no intention of becoming a musician. Even his father, the world-famous Johann Strauss Senior envisioned a career in the army for his son. But Josef Strauss had other plans, as he studied poetry, art, and engineering. In fact, he was universally talented and published two textbooks on mathematical subjects. He even invented a mechanical street-sweeper that was adopted by the city of Vienna. A shy, sickly and sensitive individual, Josef penned an anthology of poems, and “a five-act drama, for which he wrote the text, visualized the settings, and provided sketches of the characters, costumes and scenery.” According to his brothers, Josef possessed a fine bass voice and he was a virtuoso pianist. He even composed a few unpublished songs and piano pieces, but never planned for a musical career. All that changed when his brother Johann Strauss II—the waltz king—was unexpectedly taken seriously ill in 1853. Coerced by his mother to join the family waltz business, Josef became an assistant conductor of the Strauss Orchestra on a strictly interim basis. As he wrote to his fiancée Caroline, “The inevitable happened, I play for the first time. I regret with all my heart that this has happened so suddenly…” And in the exceptional compositions of Josef Strauss, art started to imitate life.

Josef Strauss’ Music of the Spheres

Pepi Strauss, as he was lovingly known by his adoring public, appeared to have had a wicked sense of humor. And he certainly proved that fact at the medical association ball of 1868. Josef Strauss was the official ball director, and according to a long-standing tradition, the music director composed and dedicated a new composition to the ball committee. Pepi Strauss did compose the waltz expected of him, but he did not take the title of the work from the ball sponsors, but instead called it “Music of the Spheres.”

Viennese Aquarelle

As a local newspaper reported disapprovingly, “the melodies of this waltz were better than their title since it gave the odd impression of being reminded of the hereafter at the medical society ball, of all places.” Be that as it may, Josef Strauss composed “one of the most impressive tone poems in all of Viennese music.” Josef Strauss was constantly looking to encode his personal experiences and his various artistic talents into music. An exceptional landscape painter, his musical “Watercolors” paints lyrical scenes offering a wide range of artistic expressions.

Josef Strauss: Aquarellen, Op. 258 (Watercolors) (Vienna Johann Strauss Orchestra; Jack Rothstein, cond.)

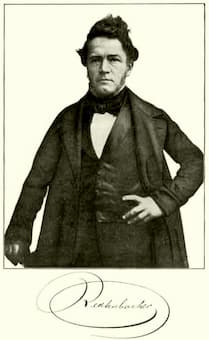

Ferdinand Redtenbacher, Mechanical engineer

First and foremost, Josef Strauss was a highly qualified engineer employed by the city of Vienna. He was constantly in touch with innovations in the world of science, and he certainly knew the theories of Ferdinand Redtenbacher. Considered the founder of science-based mechanical engineering, Redtenbacher added a mathematical foundation to previous empirical teaching. His students included the car pioneers Karl Benz and Emil Skoda.

Josef Strauss’ Waltz Dynamiden

In 1857, Redtenbacher coined the term “Dynamiden,” by which he meant the basis for the molecular forces responsible for attracting substances to each other. Basically, Redtenbacher defining magnetism, and for the Industrial Companies ball of 1865 Josef Strauss composed his waltz “Mysterious Powers of Attraction—Dynamiden,” Op. 173. The mysterious powers of this waltz subsequently attracted Richard Strauss, who quotes the opening waltz theme with only minor alterations in his opera Der Rosenkavalier.

Josef Strauss: Geheime Anziehungskrafte, Waltz, Op. 173, “Dynamiden” (Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra; Riccardo Muti, cond.)

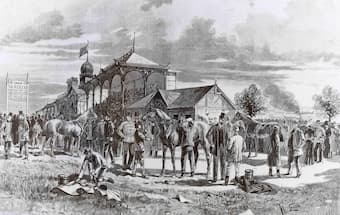

Austrian Derby at the “Freudenau” racecourse, 1896

The engineer, painter, designer, conductor and composer Josef Strauss had one more passion—horse racing. Racing started in the Viennese amusement park “Prater” in 1778, and became hugely popular in the first half of the 19th century. The “Freudenau” racecourse officially opened in 1839 in the presence of Emperor Franz Josef I. The first “Austrian Derby” was run in 1868, and it soon became an important sporting and society event. An additional horseracing track opened at the Krieau in 1878, and we know from letters that Josef Strauss placed an occasional bet or two. Officially, Josef Strauss was never seen at the racecourse, but he does make references to horse racing in a whole series of compositions, including the delightful “Jockey-Polka.” His “Steeplechase Polka,” op. 43 dates from 1857 and was premiered at the church festival at the district of Hernals. The local newspaper reports, “The Polka found such resounding acceptance that it had to be repeated several times.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Josef Strauss: Steeple chease, Op. 43 (Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra; Michael Dittrich, cond.)