In its attempts to be ever more spectacular and outrageous, French theatre began to explore the realm of the fairy (féerie) on its stages. Adding elements of the supernatural to any plot expanded its possibilities – flying through the air! Magical appearances and disappearances! Escaping from evil! – this, and more, could be accomplished with fairy assistance.

After féerie took over the French theatrical stage, a certain kind of set story developed. The storylines were basic: the action focuses on a quest, usually for love, or a struggle between opposing sides. Either storyline provided the excuse for a fantastical journey, and inspiration for the set designers to work their own magic – enchanted forests, pearl-lined caves deep in the sea, the land of the birds, and other planets were all places that could be visited.

Romantic féerie stories also involved characters from the side of darkness: the Devil and ghosts had roles, as was also reflected in the literature by Sir Walter Scott, Goethe, and E.T.A. Hoffmann. Although the first féerie stories involve all kinds of moralizing, this quickly fell away as the scene designers came to the fore. As féerie plays became more spectacular, they began to compete with the spectacle already provided by opera and so elements of féerie began to intrude onto the French operatic stage. The difference was the féerie plays only had music incidentally whereas opera was always focused on the music and the composer.

The organization of féerie plays was based on tableaux (more excuses for scene changes!) and this carried through the decline of féerie in the late–19th century and into the new genres of the musical arising in America. For example, Jerome Kern’s Show Boat of 1927 is closer to the tableaux-driven féerie genre than it is to plays with music or opera.

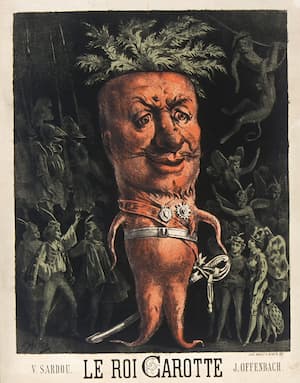

Le Roi Carotte

Jacques Offenbach composed 5 feerie operas, starting with Le Roi Carotte in 1872.

Henri Meyer: Poster for Le Roi Carotte, 1872

Jacques Offenbach: Le Roi Carotte – Overture (Philharmonia Orchestra; Antonio de Almeida, cond.)

King Carotte, magician leader of the underground kingdom, arrives with his vegetable court, deposes King Fridolin, and steals Cunégonde, his intended bride.

Design for the costume of Le Roi Carotte

King Carrot (Christophe Mortagne) and his rooted entourage appear at the royal court, 2019

(Opéra Lyon) (Photo by Blandine Soulage)

Part of the overthrow involved the animation of all the antique armor in the castle. To find a rival magician to defeat Carotte, the exiled court first finds a magician who has to be killed so he can be reanimated as a young man. He sends them off to ancient Pompeii to get a magic ring. They travel via a magic lamp, arriving in Pompeii just as the eruption of Vesuvius is imminent. They manage to get the ring and return to the modern age. Cunégonde steals the magic ring so that Fridolin cannot defeat Carotte and a witch sends him to the land of insects, which he handily defeats.

Costume design for the insects

When Fridolin and his court return home, the country is in an uproar against King Carotte due to rising prices and injustice. Carotte is defeated and is carried off by the witch. Fridolin marries, not the unfaithful Cunégonde, but the faithful Rosée du soir, who has accompanied him on his quest.

Le voyage dans la lune

Offenbach’s next opéra bouffe féerie was Whittington (1874) and then Le voyage dans la lune (1875). He took two earlier works, Orphée aux Enfers (1874) and Geneviève de Brabant (1875), and revised them to be more in the féerie mode, which was easy because their underlying stories were clearly in the fantasy genre. Other Offenbach operas, although they were staged outside the time period for féerie operas, clearly have féerie elements – we just have to remember the world of Les Contes d’Hoffmann, with its animated dolls, magical glasses, lost reflections, and devilish adversary to see how féerie lived on in opera.

Offenbach’s contribution was not to write féerie with a touch of opera, but to write operas with féerie elements. Mozart’s Don Giovanni (1787) and Die Zauberflöte (18791) were both models for this – stone guests and magical instruments are clearly predecessors – and both operas were revived in Paris in the late 19th century.

Le voyage dans la lune could not have existed without the inspiration of Jules Verne. His new line of ‘scientific fiction’, which included Voyage to the Center of the Earth (1864), From the Earth to the Moon (1865), 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1869), and many others, was the inspiration for Albert Vanloo, Eugène Leterrier and Arnold Mortier to create the libretto. When they first took it to Offenbach, he refused the project. As director of the Théâtre de la Gaîté, he declined it because of the costs to stage it. When he stepped down from the directorship, however, he took up the project with alacrity. Verne, on the other hand, was alarmed by what he regarded as plagiarism and registered a complaint with SACEM (Société des auteurs, compositeurs et éditeurs de musique) about Offenbach and his librettists’ plans. In the end, Verne let the project continue, perhaps seeing more to his advantage in letting it go.

Jacques Offenbach: Le voyage dans la lune – Act I: Ouverture (Orchestre National Montpellier Languedoc-Roussillon; Orchestre National Montpellier Occitanie; Opéra Orchestre national Montpellier; Pierre Dumoussaud, cond.)

The storyline is of the feerie style: King V’lan wants to abdicate in favour of his son, Prince Caprice. The Prince declines the honour because it would interfere with his love of traveling. He wants to travel to the moon, and the King tells Caprice’s tutor, Microscope, to make it possible. Microscope creates a cannon (as in Verne) to propel them on his way. At the last minute, the king joins the prince in the cannon and orders Microscope to come with them.

They arrive at the moon, but the Selenites are angry at the invasion and threaten to imprison all of them.

Jacques Offenbach: Le voyage dans la lune – Act II Tableau 5: La Lune: Ah! (Choeur National Montpellier Occitanie; Opera National de Montpellier Chorus; Orchestre National Montpellier Languedoc-Roussillon; Orchestre National Montpellier Occitanie; Opéra Orchestre national Montpellier; Pierre Dumoussaud, cond.)

They are saved by King Cosmos of the Moon’s daughter, Fantasia. When King Cosmos learns that he nearly imprisoned a fellow King, he releases him. V’Lan learns that there is no love on the moon and that women are merely art objects, and are traded on the market like the Earthlings trade stocks and shares.

The travellers visit various exotic locales on the moon: King Cosmos lives in a glass palace, with mother-of-pearl galleries. A local park at night has roaming shadows and phantom-like creatures with transparent heads. Cosmos’ garden has a scene with dancing stars and chimères.

Caprice loves Fantasia but she doesn’t love him (no Selenite knows love), so he eats an apple. She tastes the apple and love blossoms. King Cosmos tries the apple only to find out that his wife Popotte only has eyes for Microscope.

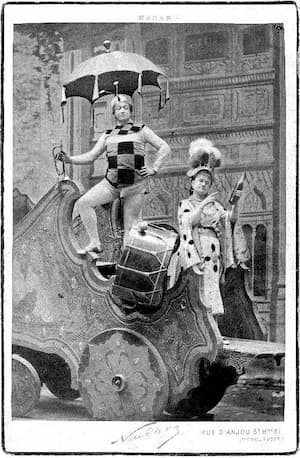

Christian (V’lan) and Zulma Bouffar (Prince Caprice) in Le voyage dans la Lune, in the charlatans scene, 1875 (Photo by Nadar)

King Cosmos, angry, throws our heroes into a volcano with no food but as he’s leaving them, Queen Popotte removes the basket in which he descended into the volcano and abandons him. Cosmos promises to free the travellers if they can find a way out. The lunar volcano erupts. The 20th tableaux merely says:

TWENTIETH TABLEAU:

THE ERUPTION

The whole stage is filled with fire and smoke. Microscope has taken refuge on the ramp at the rear stage, which he climbs with difficulty. No sooner has he reached the middle than an explosion is heard. The rock on which he is perched is thrown into space with him. V’lan and Cosmos run around the stage in panic, looking for a way out. Lava invades the stage.

Now that everyone is back on the surface, King Cosmos keeps his promise and all is well again. The opera closes with the 23rd Tableau, where the earth has risen above the lunar horizon, and all sing in salute to the rising planet.

Jacques Offenbach: Le voyage dans la lune – Act IV Tableau 23: Clair de Terre: Terre! Ah! Nous te saluons, ô terre! (Choeur National Montpellier Occitanie; Opera National de Montpellier Chorus; Orchestre National Montpellier, Orchestre National Montpellier Occitanie, Pierre Sumoussaud, cond.)

The important difference between Verne’s novel and the opera is that in the novel, the adventurers only circle the moon – Offenbach’s travellers land there and interact with the lunar inhabitants.

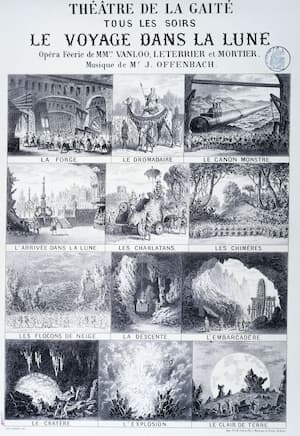

Poster for the production

As you can see in the poster for the production, every effort was made to make this a spectacle of the highest order – the cannon, the lunar civilization, the descent into the volcano, and the final Earthrise are all depicted.

The volcano set was the highlight of the show – created by Chéret, it involved seven different transformations: ‘In addition to presenting the crater and the interior of the mountain, the stage engineers depicted, in succession, the descent into the depths of the cavity, an eruption with a shower of ash, and a superb final ‘earthlight’ effect’. 676 costumes were designed for the players.

The opera continued to have an effect in French media: we can look to Georges Méliès’ ground-breaking 1902 film, Le voyage dans la lune, to see how the story carried into the 20th century.

Méliès: Le voyage dans la lune, Arrival on the moon, 1902

Operas are fantastical enough: love at first sight, sopranos and tenors’ ability to sing long arias as they are dying, long-lost children who are found in the most obvious places, and so on, that the addition of féerie elements was just one more thing to increase the excitement for the audience.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter