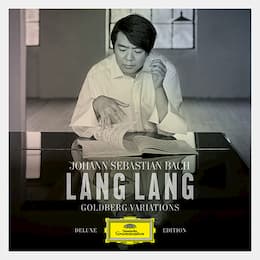

© Deutsche Grammophon

Bach’s Goldberg Variations have long been regarded as “a musical Everest”. As soon as Lang Lang’s recording was issued by Deutsche Grammophon, it instantly attracted attention from classical music aficionados worldwide and very polarised reviews from music critics – from “Lavish Lang Lang recording suffocates the magic”, “Lang Lang: The Pianist Who Plays Too Muchly” to “bridging musical objectivity and strong personality”. Some may say his interpretation is personal or original, while some may claim it’s a sacrilege. Is there actually a fine line between the two?

To me, whether an interpretation is original or sacrilegious is mostly determined by its faithfulness to the composer’s intentions while injecting one’s own insights. This may sound ambiguous and, again, very subjective. We can only get closer to the composer’s intentions by studying the history of not just the composer, but also the socio-cultural context, the style of playing at that time and the score itself. However, this is particularly difficult for Bach’s music, since Bach, just like every other Baroque composer, left little indication on his manuscripts and offered much interpretive freedom for the performers. That being said, it doesn’t mean that the performer can do whatever he or she wants to.

J.S. Bach: Goldberg Variations, BWV 988 (2020 Berlin Studio Recording) – Variatio 5. a 1 ô vero 2 Clav. (Lang Lang, piano)

© Roman Pilipey/EPA, via Shutterstock

Although Lang Lang’s formidable pianistic techniques served the music well in the faster variations (despite some harshly attacked accents), his recording was permeated with mannerism and affectation, together with over-indulgence and a tendency to over-stretch phrases, in particular in the slower sections.

Take Variation 15 (canon at the fifth) as an example, Bach himself marked Andante, which means at a walking pace. Yet, Lang Lang’s playing here was so painfully slow to the extent that the music had become static, not to mention the puzzling lingering at the end. I’m not suggesting that musicians have to strictly follow every notation on the score, but every deviation from the score should be meaningful. One couldn’t help but wonder if this was really what Bach intended.

J.S. Bach: Goldberg Variations, BWV 988 (2020 Berlin Studio Recording) – Variatio 15. Canone alla Quinta. a 1 Clav. (Lang Lang, piano)

That’s how this Variation would sound at a more reasonable tempo with a sense of flow:

J.S. Bach: Goldberg Variations, BWV 988 – Variatio 15. Canone alla Quinta. a 1 Clav. (András Schiff, piano)

In an interview, Lang Lang said the 26th Variation for him was like an aircraft taking off. I was indeed amazed to learn that airplane was invented in the 18th century!

J.S. Bach: Goldberg Variations, BWV 988 (2020 Berlin Studio Recording) – Variatio 26. a 2 Clav. (Lang Lang, piano)

Jokes aside, Glenn Gould also played this variation at lightning speed, but with much greater clarity and evenness:

J.S. Bach: Goldberg Variations, BWV 988 – Variatio 26. a 2 Clav. (Glenn Gould, piano)

The 30th variation (Quodlibet. a 1 Clav.) is a humorous mashup of German folk songs, including “Ich bin so lang nicht bei dir g’west” (I’ve been away from you so long) and “Kraut und Rüben haben mich vertrieben” (Cabbage and turnips have driven me away). It’s actually a tradition of Bach’s family to mix different tunes (sometimes even indecent ones!) and improvise during gatherings. I’m very sure that Lang Lang was aware of this as well, so why did he choose to play it in such a matter-of-fact manner?

J.S. Bach: Goldberg Variations, BWV 988 (2020 Berlin Studio Recording) – Variatio 26. a 2 Clav. (Lang Lang, piano)

Here’s a lively rendition by Wanda Landowska – full of energy and humour:

J.S. Bach: Goldberg Variations, BWV 988 – Variatio 30. Quodlibet. a 1 Clav. (Wanda Landowska, harpsichord)

There’s nothing intrinsically wrong with idiosyncrasies, but they should never override the essence of the music per se. Being peculiar doesn’t necessarily mean being original. Originality stems from true understanding of the music, which ultimately comes from scholarship, daily inspirations and a good taste.

Note:

As an extension of the discussion above, I’d like to refer to Sokolov’s performance of Bach’s French Overture.

This is so different from any other recordings of this piece, as Sokolov infused such unparalleled rhythmic vitality into the music. Listen to how he intentionally sped up when the fugue was repeated at 4:48. Does the score ask for that? No. But it makes perfect sense to create a different effect in the repeat and this indeed adds brilliance to the music, which is particularly befitting of an overture written in French Baroque style. This is what I consider to be true originality – a product of intellect and musicality.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Listen to Irina Zahharenkova’s recording of Goldberg Variations. Her interpretation and subtle innovation breathes welcomed new life into this important Bach standard.

I so enjoyed this post, Anson. (I found you through your Youtube post on Yunchan Lim’s Amsterdam performance.) I have to admit one major problem I have with Lang Lang is watching him. So smug. But I’ll further admit that the Variation 15 that you post here was rather intriguing. Bach’s music has been so intriguengly been open to any kind of fiddling about (haven’t yet done on cowbells, but somebody somewhere must have done it!) that I think I’ve been weaned from nearly any expectation of how his music will be transformed. Glenn Gould brought me to Bach way back when as I listened to the amazing beauty of the whole overarching Goldberg suite. (Of course, I AM Canadian, so….) And to me, his performance(s) of it are still my benchmark for listening to other interpretations. While I’m hear, let me say how much I admire your care in posting, and so I’ll now explore further. And if you haven’t come across Mark Ainley’s posts on Facebook, you will undoubtedly appreciate hi loving research and posts on pianists. Thanks, Anson!