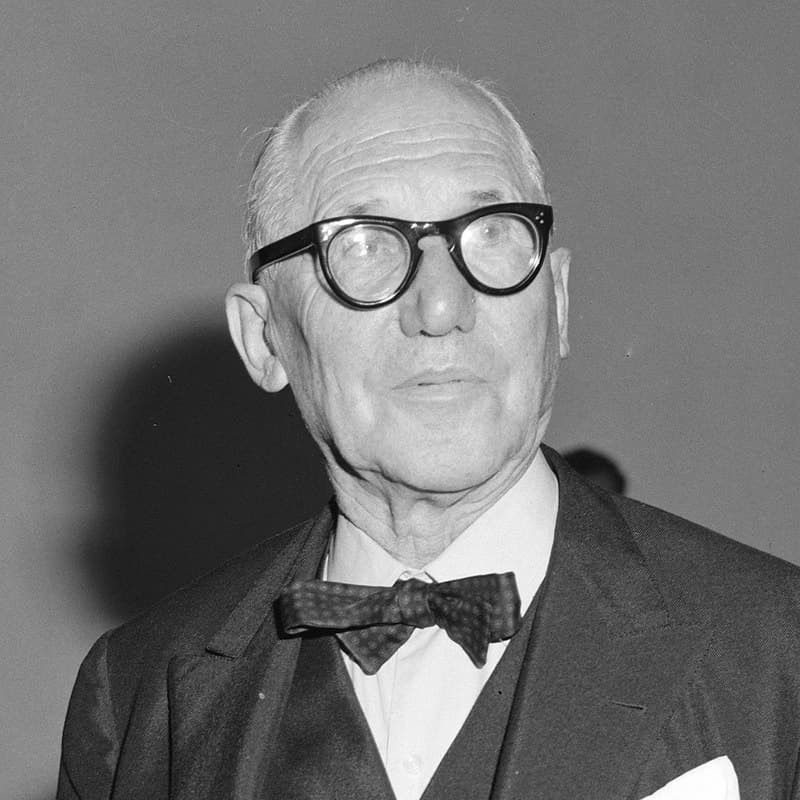

Le Corbusier

Born in a small town in the Swiss Jura region famous for precision watchmaking on 6 October 1887, Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, later known as Le Corbusier, was one of the great pioneers of Modernism in architecture. His designs, buildings, and urban planning “combine the functionalism of the modern movement with a bold sculptural expressionism.” Largely self-taught, he created celebrated buildings including the Villa Savoye outside Paris, Notre Dame du Haut in Ronchamp, France, and the Unité d’Habitation in Marseille. Dedicated to providing better living conditions for residents of crowded cities, he prepared the master plan for the city of Chandigarh, India, and contributed specific designs for several government buildings. His career spanned five decades, and seventeen projects in seven countries are inscribed in the list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites. In addition, Le Corbusier was a painter, sculptor, writer and furniture designer. He belonged to the first generation of the so-called “International School of Architecture” and he consigned the functional aspirations of his generation into concrete forms.

Iannis Xenakis: Metastasis

Le Corbusier: Villa Savoye

Young Jeanneret left school at the age of 13 to learn his father’s trade and became an engraver and enamel decorator of watch faces. To that effect, he studied drawing at the La-Chaux-de-Fonds Art School under the influential Charles L’Eplattenier. Le Corbusier later wrote that L’Eplattenier “taught him about painting from nature.” And it was L’Eplattenier who decided that Le Corbusier should become an architect. Le Corbusier wrote, “I had a horror of architecture and architects… I was sixteen, I accepted the verdict and I obeyed. I moved into architecture.” His architecture teacher in Art School was architect René Chapallaz, and Le Corbusier supplemented his education by visiting museums and libraries, and reading about architecture and philosophy. He designed and built his first houses under the supervision of his teacher, and he took a number of trips around Europe. Le Corbusier discovered the classical proportions of Greece and Renaissance monasteries in Florence. As he later wrote, “It was the solution for a unique kind of worker’s housing, or rather for a terrestrial paradise.” Le Corbusier worked in several different architectural offices: in Paris (1907) under Auguste Perret, an expert in reinforced concrete; in Vienna (1908) under Josef Hoffmann, and in Berlin (1910-11) under Peter Behrens.

Edgar Varèse: Ionisation

Le Corbusier: Philips Pavilion

At the end of World War I, Le Corbusier started an intense study of the use of reinforced concrete as a building material. “Reinforced concrete provided me with incredible resources,” he later wrote, “and variety, and a passionate plasticity in which by themselves my structures will be the rhythm of a palace, and a Pompeian tranquility.” Reinforced concrete provided “Le Corbusier with the grammar for a new, purified architecture. It provided him with construction means capable of revolutionizing the elements and the syntax of the discipline.” Reinforced concrete was offering Le Corbusier as an artificial material, homogeneous and tested in the laboratory, “which can be strictly determined by means of calculation and offer an accurate execution through the use of metal formwork, which, reinforced by the homogenizing action of roughcast, can obliterate any reference to the hand of man.” Le Corbusier was looking for purism in formal terms, and purity associated with geometry and the smooth surfaces typical of industrial production, “leaving behind any traces of craftsmanship or of the heterogeneity of the natural material.” For Le Corbusier, it was a system of construction that provided utmost freedom with regard to ground and interior arrangement. “It is a matrix that boosts architectonic events for the rich and for the poor, for the working-class house and for villas.”

Iannis Xenakis: Concret PH

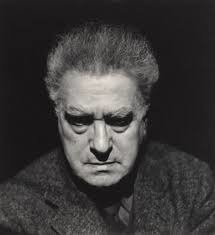

Iannis Xenakis

Le Corbusier had actually grown up in a music family, as his mother was a piano teacher and his elder brother Albert an amateur violinist. As such, he considered himself a “musician at heart,” and he was fascinated by the idea that music was able to generate infinite solutions from a scarcity of means. In addition, he believed that “music was governed by simple, clear and economic rules.” According to Le Corbusier “music had gone further than architecture and was an example to be followed.”

Edgar Varèse

As he wrote, “how many of us know that in the visual sphere, in the matter of lengths, our civilizations have not yet come to the stage they have reached in music? Nothing that is built, constructed, divided into lengths, widths, volumes, has yet enjoyed the advantage of a measure equivalent to that possessed in music, a working tool in the service of musical thought.” A symbiotic relationship between architecture and music was firmly established between 1947 and 1959, a period of close collaboration between Le Corbusier and his assistant, the composer Iannis Xenakis, and also with Edgar Varèse. Xenakis started to integrate music with architecture, “designing music for pre-existing spaces, and designing spaces to be integrated with specific music compositions and performances.”

Le Corbusier: Convent of Sainte Marie de la Tourette

Xenakis was involved in several Le Corbusier designs, including the Convent of Sainte Marie de la Tourette, the Maison de la Culture at Firminy, and probably most famously, the Philips Pavilion at the Brussels World Fair in 1958. In contrast to Modernism in architecture, however, Modernism in music “failed to alter fundamentally the tastes and practices of 20th-century mass culture. Film music and commercial advertising music did not come to reflect whatsoever architectural Modernist innovations.” Le Corbusier is a controversial architectural figure with links to fascism and anti-Semitism, but he left a visible mark on the world, “in the form of buildings he designed and the influence of his architectural theories on others.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Edgar Varèse: Poème électronique