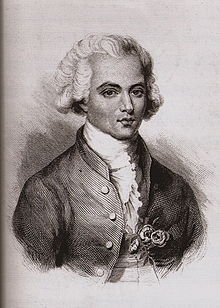

The Young Saint-Georges , 1768

Joseph Boulogne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges (1748-1799) was the darling of French Society, and he was one of the most accomplished men of his age. Born in St. Dominique—now Haiti—to a wealthy plantation owner and his black Senegalese slave Nanon, “said to be the most beautiful woman in the French West Indies,” he was considered the finest swordsman in Europe. A superb all-around athlete and military commander during the Revolutionary period, he was also among the most important musicians in Paris in his days.

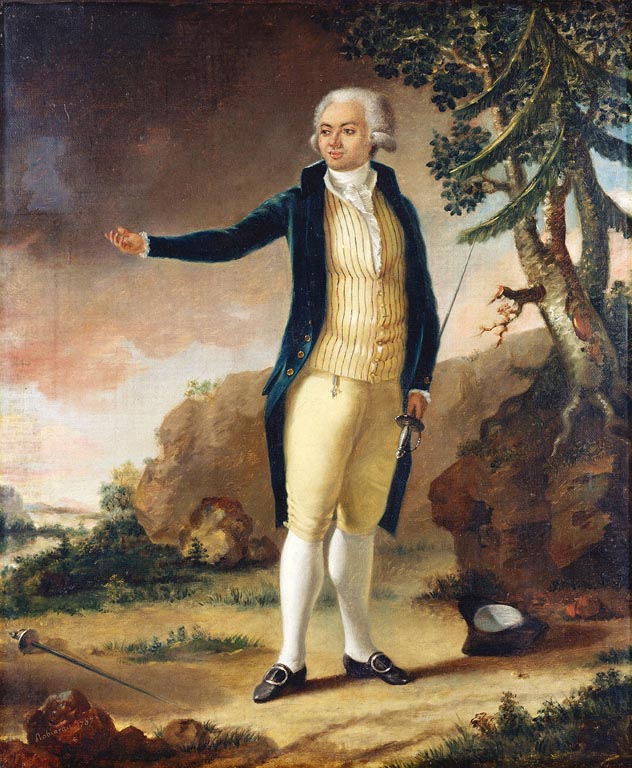

Greatly admired and dubbed “Le Mozart Noir,” the Chevalier de Saint-Georges is “unique in the history of music and the man himself scarcely less extraordinary than the phenomenal range of his talents.” His company was highly sought after, and a fellow swordsman wrote, “Saint-Georges combined in his person his mother’s grace and good looks and his father’s vigour and assurance. He was tall, handsome, and gifted: a fashionable and welcome guest in the salons, where his musical talent eventually came to the fore.” In addition, rumours about the romantic conquests of the “Black Don Juan” spread just as quickly.

Greatly admired and dubbed “Le Mozart Noir,” the Chevalier de Saint-Georges is “unique in the history of music and the man himself scarcely less extraordinary than the phenomenal range of his talents.” His company was highly sought after, and a fellow swordsman wrote, “Saint-Georges combined in his person his mother’s grace and good looks and his father’s vigour and assurance. He was tall, handsome, and gifted: a fashionable and welcome guest in the salons, where his musical talent eventually came to the fore.” In addition, rumours about the romantic conquests of the “Black Don Juan” spread just as quickly.

Joseph Boulogne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges: Violin Concerto No. 10 in G Major (Zhou Qian, violin; Toronto Chamber Orchestra; Kevin Mallon, cond.)

Chevalier de Saint-Georges

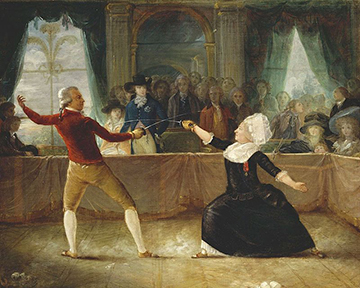

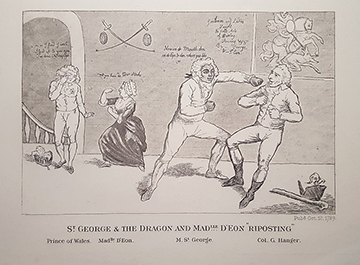

His father was a minor nobleman who took his unconventional family—his legal wife Elizabeth, his slave mistress Nanon and his illegitimate son Joseph—to Paris in 1759. Joseph enjoyed a good many of the privileges of upper-class French society. He had a good education, dressed very well and very gentlemanly, and he lived in St. Germain—still a nice part of Paris. Joseph received his education at the Royal Academy of Arms, and astounded his teachers with his talents for fencing, riding, boxing, skating, swimming, running, target shooting, and dancing. Under the guidance of the master swordsman Nicolas Texier de la Boëssière, Joseph became an expert fencer and began to compete against the best swordsmen of Europe.

When the fencing master Alexandre Picard publically hurled racial abuse at Joseph, Joseph challenged him to a fencing duel and won the match. It was reported that Joseph could “swim across the Seine with one arm tied behind his back,” and the future US president John Adams reported on his skills as a marksman. He wrote in his diary, “He will hit the Button, any Button on the Coat or Waistcoat of the greatest Masters. He will hit a Crown Piece in the Air with a Pistol Ball.” Seemingly destined for a military career, Joseph graduated in 1766 and was made an officer in the court of King Louis XV. And that’s how Joseph Boulogne became “Le Chevalier de Saint-Georges.”

When the fencing master Alexandre Picard publically hurled racial abuse at Joseph, Joseph challenged him to a fencing duel and won the match. It was reported that Joseph could “swim across the Seine with one arm tied behind his back,” and the future US president John Adams reported on his skills as a marksman. He wrote in his diary, “He will hit the Button, any Button on the Coat or Waistcoat of the greatest Masters. He will hit a Crown Piece in the Air with a Pistol Ball.” Seemingly destined for a military career, Joseph graduated in 1766 and was made an officer in the court of King Louis XV. And that’s how Joseph Boulogne became “Le Chevalier de Saint-Georges.”

Joseph Boulogne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges: Symphonie Concertante, Op. 13 (Jaime Laredo, violin; Miriam Fried, violin; London Symphony Orchestra; Paul Freeman, cond.)

Chevalier de Saint-Georges, 1787

Nobody knows for sure when Joseph took up music. Since his father was a notable patron of music who had received dedications from among others Antonio Lolli and Carl Stamitz, it is possible that Joseph studied with the violinist Jean-Marie Leclair and the composer François-Joseph Gossec. Saint-Georges became an orchestral violinist under Gossec in the newly established “Concert des Amateurs.” He made his solo debut with that orchestra in 1772, performing his two Violin Concertos Op. 2. When Gossec left a year later, Saint-Georges was put in charge of the orchestra, considered one of the best in Europe. He even commissioned six symphonies by Joseph Haydn, which he conducted himself, and he composed string quartets, concertos and symphonies. For a while he was Marie Antoinette’s music teacher, and popular theory suggests, “that even Mozart was jealous of his popularity.” When the Paris Opera needed a new director, the Queen put forth his name, and Louis XVI agreed with Saint-Georges’ appointment. However, some leading ladies of the opera company presented a petition to the Queen stating, “their honour and the delicate nature of their conscience made it impossible for them to be subjected to the orders of a mulatto.” As the result of this blatant discrimination, Saint-Georges’ nomination was withdrawn and the job left vacant.

Joseph Boulogne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges: String Quartet, Op. 1, No. 5 (Jean-Nöel Molard String Quartet)

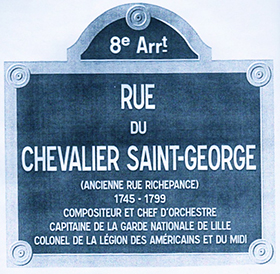

Saint-George was hugely successful as a violinist, conductor and composer. With the coming of the Revolution, however, his musical career came to a sudden halt. Although a good many of his friends were from the aristocracy, when the Revolution proclaimed the equality of all men in 1789, Saint-George joined the National Guard against them. He led the “Légion Saint-Georges”—a troop of 1,000 black soldiers—against all enemies of France. At some point he spent eighteen months in prison and subsequently made a living relying on his abilities as a swordsman and athlete. A good many of his compositions were lost during the Revolution, and what survived was quickly forgotten. Cultural critiques have suggested, “The chains of race behind him were pulling him back.” However, a couple of decades ago, the Chevalier was once again made visible, not simply for the colour of his skin but for the quality of his music. And contemporary composers, including George Walker, are recognizing Saint-Georges today. He brought “Le Mozart Noir” to our attention in 2010 with his Foils for Orchestra (Homage à Saint George). The title suggests swords used in a fencing match, musically encoded in the opening octave. After various thrusts and parrying, “the victor emerges scarred, but triumphant.”

Saint-George was hugely successful as a violinist, conductor and composer. With the coming of the Revolution, however, his musical career came to a sudden halt. Although a good many of his friends were from the aristocracy, when the Revolution proclaimed the equality of all men in 1789, Saint-George joined the National Guard against them. He led the “Légion Saint-Georges”—a troop of 1,000 black soldiers—against all enemies of France. At some point he spent eighteen months in prison and subsequently made a living relying on his abilities as a swordsman and athlete. A good many of his compositions were lost during the Revolution, and what survived was quickly forgotten. Cultural critiques have suggested, “The chains of race behind him were pulling him back.” However, a couple of decades ago, the Chevalier was once again made visible, not simply for the colour of his skin but for the quality of his music. And contemporary composers, including George Walker, are recognizing Saint-Georges today. He brought “Le Mozart Noir” to our attention in 2010 with his Foils for Orchestra (Homage à Saint George). The title suggests swords used in a fencing match, musically encoded in the opening octave. After various thrusts and parrying, “the victor emerges scarred, but triumphant.”

George Walker: Foils for Orchestra, “Homage à Saint George” (Sinfonia Varsovia; Ian Hobson, cond.)