The romance and its successor the mélodie was one of the main genres cultivated by Les Femmes “Compositeurs.” A mélodie is a form of French art song that is somewhat comparable to the German Lied. Claude Debussy wrote as follows, “clarity of expression, precision and concentration of form are qualities peculiar to the French genius. These qualities are indeed most noticeable when again compared with the German genius, excelling as it does in long, uninhibited outpourings, directly opposed to the French taste, which abhors overstatement and venerates concision and diversity.” Primarily scored for piano and voice, the mélodie is noted for its deliberate and close relationship between text and melody. However, as Debussy suggested, the mélodie “is an art that is more objective, more intellectual than that of the lied, an art of suggestion in which feelings and emotions are refined and purified, an art that deals much more with sensitive impressions and perceptions than with direct emotions.”

Henri de Bréval: The concert in the salon

The great French singer Pierre Bernac has written that “the Lied is essentially a Romantic phenomenon, whereas the French mélodie is post-Romantic and often reacts against sentimental effusion.” And a scholar adds, “it combines precision with lyricism to achieve a controlled profundity that does not preclude sensuousness of sound, beauty of sonority or subtle harmony. We find that profundity is mitigated by a lightness of spirit and wit that are characteristically French.” To compose or interpret mélodies, one must have a sensitive knowledge of the French language, French poetry, and French poetic diction.” The music anthology released by the Palazetto Bru Zane includes a good number of mélodie composed by Les Femmes “Compositeurs.” It’s very clear that one of the so-called secondary genres “did not only produce works of negligible stature.” So let’s get started with beautifully crafted mélodies by Hedwige Chrétien.

Hedwige Chrétien: Petits Poèmes au bord de l’eau

Hedwige Chrétien

Hedwige Chrétien: Petits Poèmes au bord de l’eau (Cyrille Dubois, tenor; Tristan Raës, piano)

Hedwige Chrétien (1859-1944) was born in Compiègne and her maternal grandfather, Jules Ternizien, was a professional violinist. She entered the Paris Conservatoire in November 1872 and attended classes in solfège (Lebel), keyboard and piano (Massart), harmony, and subsequently counterpoint and fugue (Guiraud). She also took organ lessons from César Franck, who called her “a remarkable student, and very hard-working.” Chrétien competed in countless composition competitions, winning a prize from the Société des Compositeurs de Musique in 1886 for the poème lyrique “L’Année.” Her marriage to the flautist Paolo Gennaro was a tumultuous affair, and the custody battle ended up in court. Chrétien joined the staff of the Paris Conservatoire to teach music theory in 1890, but she quickly resigned to concentrate on her compositions.

Over the years, Chrétien composed roughly 250 works, ranging from chamber music, orchestral music, ballets, pedagogical pieces, to works for piano or organ. She wrote an operetta in 1904 (Le Petit Lunch, 1904) and composed the music for a musical comedy, Bécassine aux bains de mer, thirty years later. She also wrote over 70 mélodies, including Petits Poèmes au bord de l’eau of 1910 on poems by Ludovic Fortolis. Chrétien settings disclose clarity of writing, and “purity and richness of harmony with melodic charm joined to a very noble spiritual expression.” Remaining a faithful disciple of the classical masters, her favorite texts reference France’s medieval past.

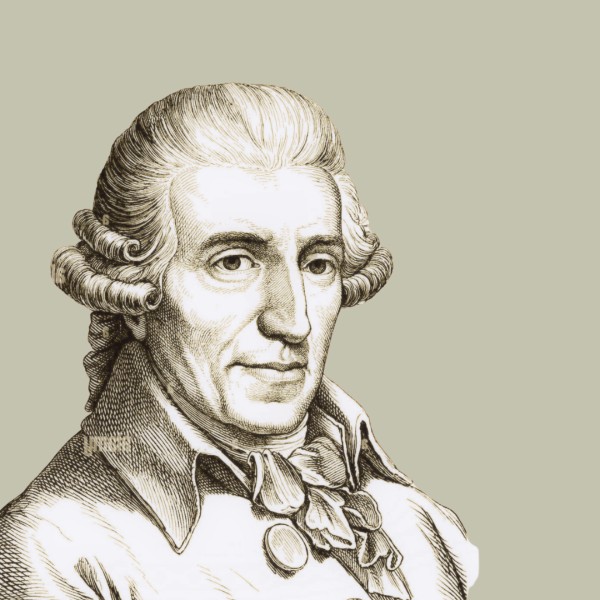

Pauline Garcia-Viardot: 12 Mélodies sur les poésies russes

Pauline Viardot

Pauline Garcia-Viardot: 12 Mélodies sur les poésies russes (excerpts) (Aude Extremo, mezzo-soprano; Étienne Manchon, piano)

Pauline Viardot (1821-1910) was the daughter of the highly esteemed tenor, composer, and singing teacher Manuel del Pópulo García and his longtime companion Maria Joaquina Sitches. Viardot was one of the most celebrated mezzo-sopranos of her time. “During a remarkable career spanning almost a quarter of a century, she performed on the most prestigious stages around the world, and her distinguished interpretations decisively shaped the history of opera in France.” Viardot purchased a summer home, the “Château de Cortavenel,” located in the Seine-et Marne region of France. She converted the attic into a small theater, and she invited the Russian poet Ivan Turgenev, with whom she had an increasingly intimate relationship, to remain in France. Turgenev encouraged her to explore Russian literature, most notably the poetry of Alexandr Pushkin.

During 1862-3 Viardot-García composed her 12 Mélodies after poems by Pushkin, Fet and Turgenev. A musicologist writes, “Pauline Viardot possessed the ability to infuse her songs with the cultural idioms respective to the language and origin of the piece. Her Russian settings exhibit her sensitivity to text, dialect, drama, and idiomatic writing. And, they reflect the early National Russian style present in the romansí of Dargomyzhsky and Tchaikovsky.”

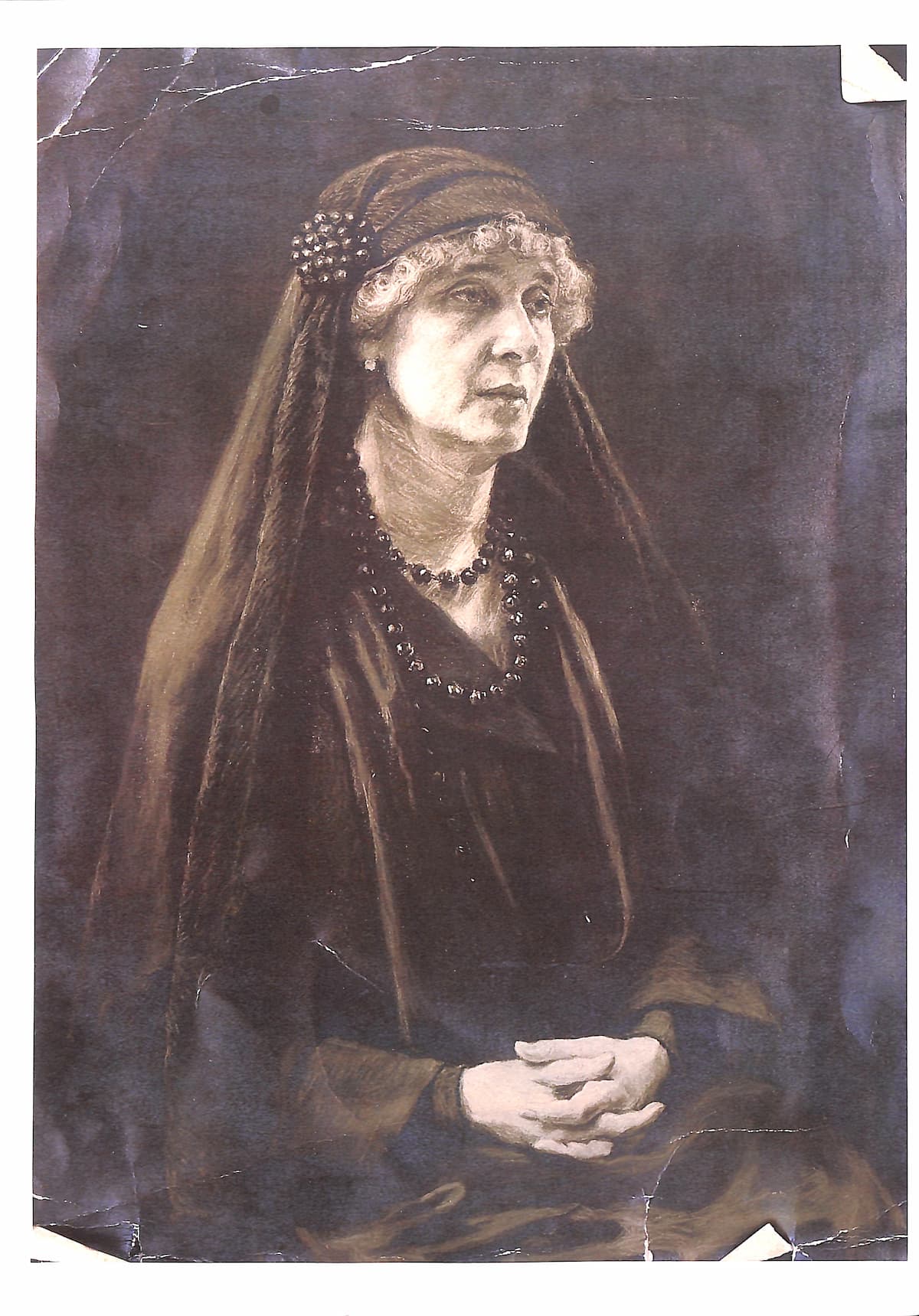

Marthe Bracquemond: 3 Mélodies

Marthe Bracquemond: 3 Mélodies (excerpts) (Cyrille Dubois, tenor; Tristan Raës, piano)

We sadly have very little available information on the organist and composer Marthe Bracquemond (1898-1973). We do know that she was the daughter of the designer and painter Pierre Bracquemond and Aline Barbedette, and that she studied with Widor, Vierne, Büsser, Dupré, and Nadia Boulanger. Bracquemond became a reputable organist and harpsichordist, performing as soloist with the Concerts Pasdeloup and holding the position of titular organist at the Reformed Church in the rue Cortambert in Paris between 1937 and 1962. Her cycle of Trois Mélodies dates from the 1920s, and it is a setting of poetry by Judith Gautier (1845-1917).

Judith Gautier, circa 1880

A distinguished Sinologist who translated Chinese and Japanese texts, Gautier was at the center of French literary and artistic circles. Gautier’s prolific output, which included novels, short stories, poetry, plays, translations, and criticism, was recognized in 1910 by her election as the first female member of the Académie Goncourt. A critic called the appointment “a proof of the good feminist feelings which move this literary company, and the just reward for a life completely devoted to the pure cult of literature and the arts.” Bracquemond’s declamatory settings are acutely sensitive to Gautier’s text, infusing the poetry with a dash of modal exoticism.

Madeleine Lemariey: 6 Mélodies

Madeleine Lemariey: 6 Mélodies (excerpts) (Cyrille Dubois, tenor; Tristan Raës, piano)

The name Madeleine Lemariey appears on only nine pieces published in 1904, but nobody seems to know anything about her. It might well be a pseudonym or a maiden or married name, but we simply don’t know. Scholars have speculated, “that the name likely originated in Normandy, where this kind of spelling is common.” But they also caution that there was no student of that name at the Paris Conservatoire, and that the “newspapers of the Belle Époque never mention this woman composer or disguised male composer.” Her compositions date from two specific periods of time. In 1904 she published five piano pieces in a set entitled Échos poudrés. These short pieces all carry titles associated with the Parisian salon. Nine years later, in 1913, she turned her attention to the genre of the mélodie with piano accompaniment. The pastoral romance entitled “Ma Bergère” is set to her own verse, but she also set poems by Paul Verlaine, Sagasse, and Édouard Pailleron. Almost fittingly, the famous “Sonnet of Félix d’Arvers” carries the famous first line, “My soul has its secret, my life has its mystery.”

Madeleine Jaeger: “Mélodies”

Madeleine Jaeger: La chanson du rouet (Cyrille Dubois, tenor; Tristan Raës, piano)

Madeleine Jaeger: Les Étoiles mortelles (Cyrille Dubois, tenor; Tristan Raës, piano)

Madeleine Jaeger (1868-1905), also known under her married name Madeleine Jossic or Madame Henry Jossic, was born in Mennecy. She entered the Paris Conservatoire at a very young age in 1876 and remained at the institution for fifteen years. It seems that during that time, “she collected the largest number of Premiers Prix ever awarded to a woman in that institution by that time.” She was described as an “excellent musician,” and after her marriage to composer Henry Jossic, she returned to the Conservatoire to take up an appointment as professor of music theory. In 1891, Jaeger published two mélodies on poems by Leconte de Lisle, “Les Étoiles mortelles” and “La Chanson du rouet.” The poet played a leading role in the Parnassian poetic movements, “bridging the Romantic and Symbolist periods.”

The song of the spinning wheel

O my dear spinning wheel, my white spool,

I love you better than gold and silver!

You give me everything, milk, butter and flour,

And the cheerful lodgings, and the clothing.

I love you better than gold and silver,

O my dear spinning wheel, my white spool!

O my dear spinning wheel, my white spool,

You sing at dawn with the birds;

Summer like winter, hemp or fine wool,

By you, until evening, load the spindles

You sing from dawn with the birds,

O my dear spinning wheel, my white bobbin.

O my dear spinning wheel, my white spool,

You will spin my narrow shroud for me,

When, close to dying and hunching over.

I will make my bed eternal and cold.

You will spin my narrow shroud for me,

O my dear spinning wheel, my white spool!

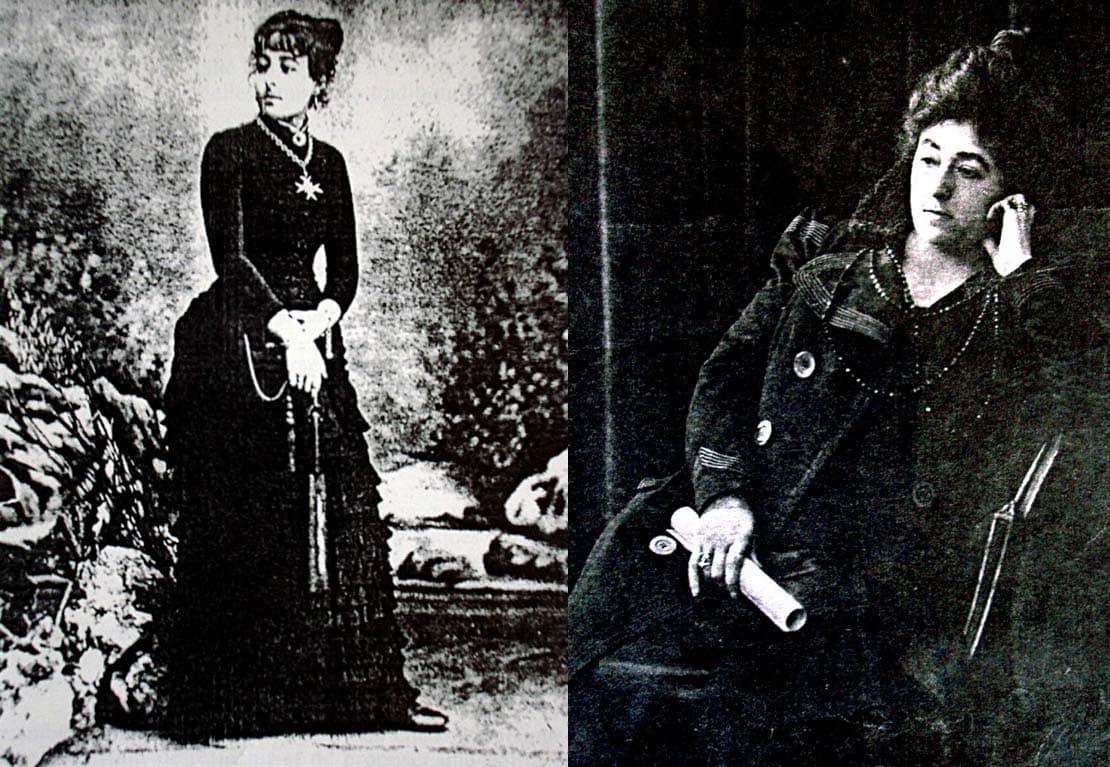

Mélanie Bonis: “Mélodies”

Mélanie Bonis in 1918

Mélanie Bonis: Invocation, Op. 5 (Laetitia Grimaldi, soprano; Ammiel Bushakevitz, piano)

Influenced by Franck, Fauré, and Saint-Saëns, Mel Bonis (1858-1937) composed roughly 40 mélodies. 28 of them are scored for baritone or mezzo-soprano, 7 for high voice, and 5 for female voice. Bonis mainly relied on poetry by Amedee Hettich, Maurice Bouchor, Edouard Guinand, Victor Hugo, Rivollet, Leconte de L’Isle, Andre Godard, Edmond Ducostal, Anne Osmond, and Madeleine Pape-Carpantier. Not to be outdone, Bonis also wrote and musically set her own poetry. As a scholar writes, “Her songs reveal a great diversity of style, ranging from the light to the very romantic, from the religious to the impressionistic. All have in common a careful scoring and are firmly anchored in the traditions of the time. The chosen texts have a charm that goes beyond time and place.” Her musical settings are at once descriptive and impressionistic, and require sophisticated interpretation on the part of both singer and pianist. Just listen to the intricate harmony in “Invocation,” a setting of poetic simplicity, charm, and sincerity. Despite her accomplishments, Bonis struggled to have her pieces published. As a publisher wrote, “I’ve had plenty of time to read the music that you sent me. In truth, I found it excellent. But, as you ask me to be completely frank, I must tell you that I find it difficult to see how to expose this very pleasant, often moving music.”

Charlotte Sohy: Les Méditations, Op. 18

Charlotte Sohy

Charlotte Sohy: Les Méditations, Op. 18 (Cyrille Dubois, tenor; Tristan Raës, piano)

Charlotte Sohy (1887-1955) composed roughly thirty-five works, including twenty mélodies. In addition, she was a highly accomplished author, writing plays and a novel. In fact, she wrote the libretto Bérengère, a drame lyrique set to music by her husband. As such, it is probably not surprising that her Les Méditations, Op. 18, dating from 1922, are settings of her own poetry. The songs were originally composed for soprano and piano and were premiered in January 1923 by Louise Matha with the composer at the piano. The mélodies are striking, as Sohy combines her great lyrical and dramatic power with flawless word settings thanks to her literary and declamatory talents. As a critic writes, “the purity of these mélodies are marked by the strong personal faith of the composer, and require a performance that constantly pays attention to the colours of the poetry and music.”

Marie Jaëll: Les orientales, No. 3 “Rêverie”

Marie Jaëll

Marie Jaëll: Les orientales, No. 3 “Rêverie” (Cyrille Dubois, tenor; Tristan Raës, piano)

Marie Jaëll (1846-1925) composed a number of mélodies, and she worked at the center of French thought and dispute on the subject. Saint-Saëns wrote to Marie Jaëll in 1876, “If you want to have your Lieder with orchestra, don’t think twice, the Lied with orchestra is a social necessity; if there were such a thing, singers in concerts would not always be performing operatic arias, which often create such a mediocre impression.” Saint-Saëns was fighting against the predominance of opera arias on concerto programs, “an artistic endeavor that also became a political fight.” The primary aim was to overhaul the “Ars gallica,” designating music by French composers, at a time when German art was taking Europe by storm. According to Saint-Saëns, “the orchestral colour should be placed in the service of the poem, which is regarded as superior to the music.” As a critic writes, “the composer should fit the lines of verse over the melody like a jeweler sets a gem.”

Rita Strohl: Douze Chants de Bilitis

Rita Strohl

Rita Strohl: Douze Chants de Bilitis

Let me conclude this little survey on Les Femmes “Compositeurs” by presenting Rita Strohl’s (1865-1941) Douze Chants de Bilitis composed in 1898. Her setting of the erotic poetry by Pierre Louÿs, although published at the same time, completely ignores Debussy’s famous setting. For Debussy, the Bilitis setting marked the beginning of a new stylistic direction. As she writes, “a mystical exaltation dominated all my feelings, making me sister to these beings who give themselves without sharing to the object of their worship, ignoring the scalpels of criticism, the speculations of the future and the preoccupations of fashion… They owe nothing but to the thought that they translated; they knew nothing of the nascent Debussysme.” Strohl apparently got the idea of setting Les Bilitis to music from her first husband. We do know that the settings were performed, probably in Brussels and Paris, but they have since been forgotten. Recorded only recently, “the music is deeply filled with humanity and celebrating femininity, and the musical nuances range from extreme intimacy to the sweetest mischief.” I have learned so much from this series on Les Femmes “Compositeurs,” but there is still so much that needs to be done to bring this wonderful repertoire to listeners today.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter