We’re so familiar with the images of Beethoven in his mature years – the glower, the intense look, the solitary figure – but when we go back in time, we can see just how his contemporaries viewed him.

The very first image we have of Beethoven dates from 1783, when he was only 13. It’s an interesting picture: he looks us straight in the eye, he has a delicate lace collar, and a decorated waistcoat with gold buttons. His blue jacket has more gold buttons. What’s most catching, however, are his big brown eyes.

Beethoven: Piano Sonata in E-Flat Major, WoO 47, No. 1, “Kurfürstensonaten” – I. Allegro cantabile (Jenő Jandó, piano)

Anonymous: Beethoven (1783)

Three years later, we have a silhouette. The elaborate lace fichu at the throat and his short but bristly hair tied back with a ribbon. He’s grown up in the past 3 years and is much more the man of fashion.

Beethoven Silhouette (1786)

The same year, Joseph Neeson captured Beethoven, again with the lace at the throat. The head is out of proportion to the body, the mouth and nose are over-sized, the eyes a bit too far apart – the throat is so wrapped that he scarcely seems to have shoulders. But, it’s his hair that seems to be in its own windstorm.

Beethoven: Piano Trio in G Major, WoO 37 – I. Allegro (Oslo Philharmonic Chamber Group)

Neeson: Beethoven (1786)

Ten years later, the 26-year-old Beethoven seems to have a real presence. He’s watching us closely, but with his head turned. His build is slight. This three-quarter’s pose is better at capturing his quiet potential. Again, his hair, although held in a queue, still waves wildly about his head.

Stainhauser: Beethoven (1796)

A similar portrait done in 1803 by Carl Riedel shows him with an even higher neck cloth and the same wild hair.

Beethoven: Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 36 – III. Scherzo: Allegro (Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra; Roger Norrington, cond.)

Riedel: Beethoven (1801)

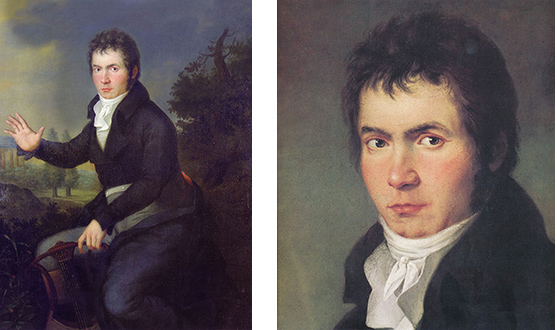

Christian Horneman’s 1803 portrait of the 33-year-old Beethoven starts to capture the face that we’re more familiar with. The face has broadened, the lips are more defined, his cleft chin is more prominent, and still, the hair goes everywhere.

Horneman: Beethoven (1803)

Joseph Willibrord Mähler shows us a less controlled Beethoven – the previously prominent chin is tucked down, the eyebrows are unbrushed as is his hair. He’s shown in a classical background – temple columns and poplar trees behind him while he holds a lyre, speaking to his occupation as a composer.

Left: Mähler: Beethoven (1804)

Right: Portrait in details

Ludwig Schnorr von Carolsfeld drew a quick sketch of Beethoven around 1808 or 1809 – the sideburns are long and the hair is wild.

Carolsfeld: Beethoven (1808-09)

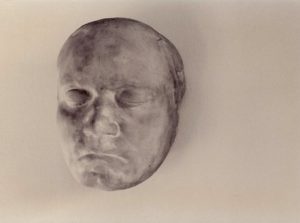

Painting, of course, is an interpretation. How did the great man really look when the painter wasn’t putting in his own style? One way of capturing a likeness was to do a life mask. The subject would have his face covered with a cloth, cotton pads placed over his eyes, two straws inserted in his nose so he could breathe, and then plaster piled on top. This was done to Beethoven in 1812 by Franz Klein, at the request of the Streicher family. The Streichers were a famous piano-making company in Vienna and they wanted a bust of Beethoven for their new fortepiano warehouse. The Streicher family tells the story that to get the mask, it was necessary to do the process two times because Beethoven was afraid of suffocating under the heavy plaster and it took two tries to accomplish this. In fact, there was never a second attempt made because Beethoven ran away from the whole process. Klein took the smashed mask (Beethoven had torn it from his face and thrown it across the room) and was able to put it back together as it had already partially set. The mask held by the Beethoven Haus, Bonn, called the “Bodmer” mask is thought to be the original cast taken from the Klein process.

Beethoven: Die Ruinen von Athen, Op. 113 – Overture (Turku Philharmonic Orchestra; Leif Segerstam, cond.)

Klein: Beethoven Life Mask (1812) (“Bodmer,” Beethoven-Haus, Bonn)

Over time, as more casts were made and romanticism set in, the face was smoothed out, sometimes hair was added, sometimes a laurel-wreath circled the hair, open eyes might be added – a whole range of versions can be seen on the Beethoven-Haus Bonn website. In the original mask, however, you can see his facial scars and enlarged pores – these are missing from later versions. What you also see is determination and a strong will.

Klein: Beethoven Life Mask (1812) (smoothed)

In 1814, Louis Rene Letronne depicted Beethoven with a high collar, simple neckcloth, and still that hair.

Letronne: Beethoven (1814)

He appears slightly differently in a pencil drawing Letronne did that same year – the face is broader and shorter, the lower lip fuller, the chin smaller, the side burns more prominent and the hair somewhat pushed back.

Letronne: Beethoven pencil sketch (1814)

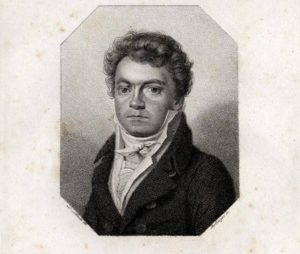

In a later engraving of the Letronne image, the hair is made into more standard curls, the eyebrows are filled out, and the eyes made much larger.

Bollinger: Beethoven (1820) (Engraving by Friedrich Wilhelm Bollinger after the engraving by Blasius Höfel based on the drawing by Louis René Letronne)

In 1815, Mähler did another portrait of Beethoven, but this time less mythic. Gone are the classical elements of columns and lyres, here the focus is on Beethoven alone.

Mähler: Beethoven (1815)

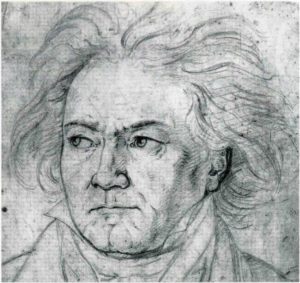

In his 1818 drawing of the 48-year-old Beethoven, August von Kloeber overemphasized the cleft chin and the hair is wilder than ever, but he was complimented by Beethoven as having captured his hair better than other painters had.

Kloeber: Beethoven (1818)

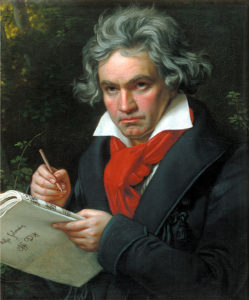

Joseph Karl Stieler’s 1820 portrait of the 50-year-old Beethoven is probably the best-known image of the composer. Beethoven is shown writing the Missa Solemnis, which he began in 1819 and finished in 1823. We notice the anomalies: why would the title of the work be written on the inside cover, why are the clefs and visible notes in ink when he has a pencil in his hand? We’ll leave all that to artistic license. One of the understood things about Beethoven was that he liked to take walks in the woods and was inspired by what he saw there – here, too, Beethoven is shown against a wooded background and he is, presumably, looking at something that’s inspiring him.

Beethoven: Missa Solemnis, op. 123 – Kyrie Eleison (Nashville Symphony Chorus; Nashville Symphony Orchestra; Kenneth Schermerhorn, cond.)

Stieler: Beethoven (1820)

That same year, Adolph Kunike did an engraving of Beethoven – but the face is different than we’ve seen before: there’s more definition around the eyes, the mouth is fuller, and the hair has been smoothed.

Kunike: Beethoven (1820)

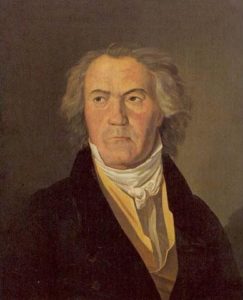

Finally in 1823, we have an image of Beethoven where we feel his years. His hair, though still wild, no longer flies away so boldly, his lips are thin, his face seems to have fallen, and now there are bags under his eyes. The artist, Ferdinand Waldmüller, was a noted Viennese painter and portraitist.

Waldmüller: Beethoven (1823)

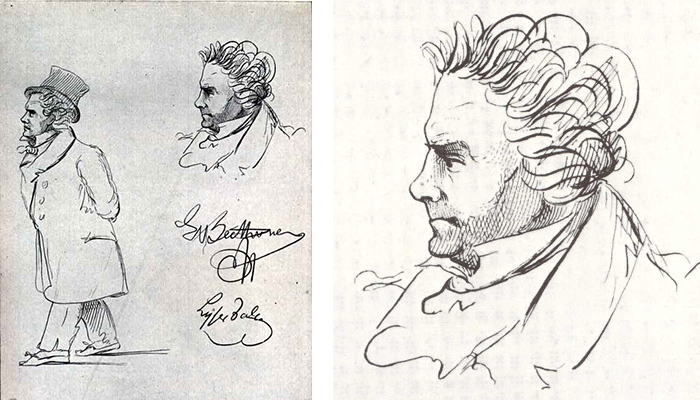

Some of the most modern-looking images of Beethoven were the caricatures done by Johann Lyser in 1825.

Left: Lyser: Beethoven caricatures (1825)

Right: Caricatures in details

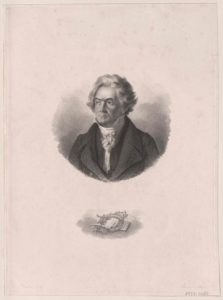

Joseph Steinmüller’s engraving of Beethoven in 1827 is a throw-back to the more familiar image, since it’s based on a drawing by Stefan Decker done in 1823, three days after Beethoven had conducted his Ninth Symphony. While Steinmüller was doing his engraving, Beethoven died and so Steinmüller added a little vignette below to symbolise that: a broken lyre crowned by a laurel wreath. Anton Schindler, Beethoven’s assistant for his last years, thought that showing Beethoven “with short hair is like painting a lion with its mane cut off.”

Beethoven: 3 Equali, WoO 30 – No. 1 Andante (Philip Jones Brass Ensemble)

Steinmüller: Beethoven (1827)

These images were all done of Beethoven in his lifetime – next, we’ll look at how he changes after his death.

Note: These are by no means all the images of Beethoven! Each music example here has been matched with the date of an image, for example, the first picture of Beethoven at 13 is matched with a work he wrote that year. The last work, 3 Equali, was performed at Beethoven’s funeral in an arrangement for voices.