Anon: François Couperin (Château de Versailles)

How does a composer look at himself? In these works, covering some 400 years, we’ll see composers’ self-portraits in music and try to discern how they saw themselves.

Seeing himself in an allemande rhythm, the French composer François Couperin (1668-1733) wrote himself into his Pieces de Clavecin, Book 4 (1730), one of his final publications before his death in 1733. In this work, we see the composer aiming for affect: he wrote once that he preferred something that touched him to something that surprised him. Consequently, starting from the harmonic writing, he also changes timbre with his alternations between melodic and lute-like passages, the juxtaposition of different registers, the harmonic steps mixed with chromaticism, and so on, giving us the image of a composer who was aware of history (the harpsichord had replaced the lute as the court instrument in France under his influence) and of his own power of composition.

François Couperin: Pieces de clavecin, Book 4: 21st Ordre in E Minor: La Couperin (Olivier Baumont, harpsichord)

The young Francis Poulenc

Francis Poulenc (1899-1963) wrote his 1921 piece Promenades about a very confused world of travel, starting on foot, to a car, on horse, in a boat, an airplane, a bus driven by a crazed driver, etc., until the final part where we are returning home in the post diligence, ‘manned by two very tired postal carriers, who are either singing or playing their post-horns in different keys.’ The work is supposed to be a self-portrait of the composer in music and what sounds like a very complicated day.

Francis Poulenc: Promenades – I. A pied (Nonchalant) (Olivier Cazal, piano)

The young Virgil Thomson with Gertrude Stein

Virgil Thomson (1896-1989) is known for his musical depictions of people he knew. His Portraits series was begun in the 1930s in Paris and continued until his death in the 1980s. Some people are still famous today, such as Alice Toklas and the writer Jane Bowles, the artist and poet Dora Maar, the Dadaist Tristan Tzara, and the conductor Eugene Ormandy, while others were of a more limited fame or known because they were part of his personal circle of friends. Thomson’s Second Piano Sonata, written in 1929, just after he completed his Gertrude Stein opera, Four Saints in Three Acts, was recognized by him some years later as his own self-portrait, to quote James Joyce: ‘a portrait of the artist as a young man.’

The Cantabile first movement is like a small child finding a piano – simple parallel lines.

Virgil Thomson: Piano Sonata No. 2 – I. Cantabile (Anthony Tomassini, piano)

The second movement, Sostenuto, becomes more complex, but it’s only in the last movement, Leggiero brilliante, that he brings in the intensity, the application of the basics, the complexity that was this brilliant critic and composer.

Virgil Thomson: Piano Sonata No. 2 – III. Leggiero brilliante (Anthony Tomassini, piano)

György Ligeti

György Ligeti (1923-2006) created his Selbstportrait mit Reich und Riley (und Chopin ist auch dabei) (Self-Portrait with Reich and Riley (and Chopin is also there)) in 1976, He was inspired by American composers Terry Riley’s In C (1964) and Steve Reich’s It’s Gonna Rain (1965) and Violin Phase (1967). As much as he uses the repetition and change found in Riley’s and Reich’s works, the piece is also about his own music, such as Continuum (1968) and other experiment works from the 1960s. And yet, at the same time, there’s a bit of the romantic side of the piano with Chopin. We’re asked to think of this as a photography of Riley, Reich, and Ligeti, while in the background Chopin is a ghostly image. The work uses the technique of “mobile blocking of the keys” where one hand holds keys down without their hammers hitting the strings, and the other hands plays on the live keys. This technique produces sounds and rhythmic patterns that are not written and which can ‘appear’ only to the listener’s ear.

György Ligeti: 3 Pieces for 2 pianos: No. 2. Selbstportrait mit Reich und Riley (und Chopin ist auch dabei) (Paola Biondi, piano; Debora Brunialti, piano)

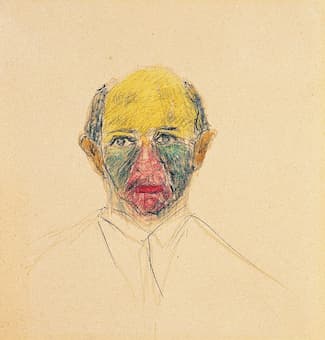

Arnold Schoenberg: Self-Portrait (1921-22)

These four self-portraits are all indicative of the composer’s art, if not exactly indicative of a living picture of the composer – we see in Couperin the changes he saw in the musical art around him. In Poulenc, it was the changes in the world around him as transportation changed and he found himself a hapless pedestrian in a world of dangerous drivers and dangerous vehicles. Thomson presents a simplified picture of his music world, without the real details that would give us more of an indication of his character. Ligeti is probably the most musically true but uses the general world of experimental music of the 1960s to create and reflect his image.

When the composer is also an artist, we can have another kind of self-portrait.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter