Lucas Debargue

© Xiomara Bender / Sony Classical

Four years have passed since the music world discovered Lucas Debargue at the 15th Tchaikovsky Competition. His peculiar path to music has created a new, different perspective on piano art. The conversation took place at the Riga Jurmala Music Festival, where Debargue ended the festival with his recital.

On October 4, it was the release of your fourth solo album, a four-disc box with 52 Domenico Scarlatti sonatas. Is Scarlatti one of your favourite composers?

When I discovered this music, it opened new world for me and this music quickly became central in my thoughts. I have a very personal contact with Scarlatti’s music.

When my passion for this music started, I wasn’t sure if I would play it in concerts. Scarlatti sonatas are used more often to open a concert or for encores. So, I did that at first. Later I met some harpsichord players and I discovered that, for them, it is normal to do recitals only with Scarlatti. When I looked more closely, I saw that Christian Zacharias played programs with only Scarlatti works and Pogorelich has done it too. For one half of his recital, he played only Scarlatti and so did Horowitz. So, I’m not the first to do that. Scarlatti sonatas are one-movement works and I usually play 10 or 11 of them in the first half of my recital program. I group them by tonalities to make associations between sonatas and create contrasts as if they were different parts of a bigger work.

Domenico Scarlatti is a somewhat enigmatic composer and not much is known about him.

That’s it. What we know is that he was composer Alessandro Scarlatti’s son and that he spent most of his life in Portugal and Spain. He was a music teacher of the Portuguese princess Maria Barbara who later became Queen of Spain. Maria Barbara was obviously a very good harpsichord player, so I imagine that she was able to play even the most difficult sonatas Scarlatti wrote for her. They were probably very close and, strangely enough, they even died almost at the same time.

The other mystery is that the manuscripts of his sonatas were not written in his own hand. We have no sketches of these sonatas. One theory is that it was Padre Soler, Farinelli, or some Scarlatti student who wrote them down from his improvisations. The scholar Ralph Kirkpatrick’s book on Domenico Scarlatti collects all the biographical elements he could find and provides an analysis of the sonatas. Information on Scarlatti came mostly from the writings of the English music historian, composer, and musician, Charles Burney, who was friends with Thomas Roseingrave, a composer and organist in London. Roseingrave knew Handel very well and when he went to Italy, he discovered the talent of Scarlatti. He was the one who took care of the first publication of some Essercizi in London.

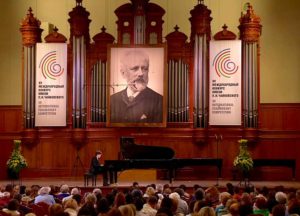

Lucas Debargue at the Tchaikovsky Competition

© www.tutti-magazine.fr

It has always seemed to me that these sonatas were written in the Baroque era, but they don’t connect well with what was written at that time.

Scarlatti lived in an environment where he was completely free to do anything. He didn’t need to please anyone. He lived in his little nest at the Spanish court, surrounded by a few friends, Farinelli among them, and he could do what he really wanted. The court was fond of him too. It is known that the queen even paid his gaming debts because Scarlatti was a gambler and he played a lot.

In the case of sonatas, there is room for experimentation. They always begin with a “bow” for the presentation. Then, in the middle part, there are strange events with some Spanish or even Arabic scales and then you have the conclusion. Scarlatti sonatas are always built like that: a presentation, harmonic, rhythmical, melodic strange events, and then a return home. The form is A-B-A, A-B-A.

Scarlatti: Keyboard Sonata in C Minor, K.115/L.407/P.100

What do you see in this music, why is it so close to you?

What I admire here is the artistic achievement what Scarlatti is able to get. These sonatas are like little mathematical problems and he has his own way of solving them, unique ways of putting things together. Sometimes he stretches time, then another time he compresses it. It is very moody music and that’s why I feel at home here because I am very moody myself.

This music never stays for long in the same place and at times becomes obsessional. The same motif is spinning around, repeating, repeating, repeating…

It is very psychological music. It plays with people’s minds. This can already be seen from how he uses repetitions. We are waiting for, say, four repetitions. Scarlatti, however, repeats five times. Instead of two times, he repeats three times. You cannot predict what is going to happen. That’s why it is to me very important to do all the repeats in Scarlatti sonatas. I also do this because when people hear these sonatas for the first time, they can’t figure everything out right away. But then they can hear it again.

The harmonies and modulations that Scarlatti uses were very unusual for his time.

Everyone talks about Scarlatti’s weird harmonies, but they’re not so weird at all, he just uses some effects such as acciaccaturas. His modulations are not unprecedented, either. We must not forget that in the Baroque era, as well as in the Renaissance, weird and special things were loved. Gesualdo, for instance did much crazier things in his harmonies. We have simply lost touch with this time.

It’s not like Romantic music where you always must pull something out of yourself. Of course, there are heart-breaking moments, some personal, tragic reflections. But mostly Scarlatti is playing with all this.

Scarlatti: Keyboard Sonata in A Major, K.212/L.135/P.155

This music needs background knowledge to be appreciated, but nowadays people expect mostly an emotional experience in music.

Scarlatti’s music is indeed harder for the audience to understand than some other music. For me, for instance, Chopin is a very complex and ambiguous composer and it is complicated to understand the nature of his music. But everyone is confident in their understanding of Chopin. People have heard something in the movies and commercials, and they’re used to it. And they don’t want to hear anything different there.

It is the same with literature. Even the most famous writers aren’t famous for what they wanted to be. Who, for instance, among Mozart music lovers knows that he only considered his 14th piano concerto worthy of being his opus 1? He wrote to his father in a letter: Today I really composed my first work! This, of course, mocks the myth of the wondrous Mozart who composed his first symphony at the age of six. Who cares now about the symphony he wrote when he was six years old? Of course, he already had technical skills and great musical experience. But Mozart was not the composer we know him by the age of six.

Now the music of Mozart, Bach and Chopin is everywhere, even at funerals and weddings. But these composers didn’t write for that. When they were dreaming of success, they were dreaming of the approval of connoisseurs and they were not writing for the world. The highest reward was the title of nobleman and for Scarlatti – as he is portrayed in his best-known preserved picture – the royal order. It was more than any artistic success.

If I’m interested in Scarlatti’s music, I’m interested in the mentality of the time and what the world was like when he composed his music. In that epoch, people had time. Especially when they were wealthy and privileged people in the court. Most of the time they had nothing to do. They just rested and felt their own boredom. One can imagine the heat in Madrid and those hours spent on terraces amidst the beautiful gardens seeking coolness. Hours and hours of total emptiness and boredom. For me, this is the landscape of the music of Scarlatti. We are bored – let’s get bored together in music! Nowadays people don’t have that kind of time anymore and that’s why I’m convinced this music is kind of shocking. It doesn’t talk too much about our way of living. If we listen to Tchaikovsky, it is already our world, the notion of industrial time and we hear the rhythm of trains. The music reaches a culmination and listeners feel the satisfaction.

But at that time there was not the same feeling of the climax. The people who listened to music didn’t expect a big crescendo and climax. There is time for silence. It’s theatre. It’s very theatrical.

I love this music because when I play it, I join Scarlatti’s time. Blaise Pascal had the same sense of time. By the way, they had a common interest to science. Scarlatti was fascinated by science and attended a conference in Lisbon about space. At that time, there was time to sit, think and discuss stars, planets, the evolution of the world, and there was no need to watch the clock all the time. Time was time and when you were in it nothing else existed. When I play Scarlatti sonatas, nothing else exists.

It’s radical music. Only few notes, no fortissimo, not even dynamics are written. If you want to enter this world, you must accept the rules. When you hear Rachmaninoff or Tchaikovsky, they don’t ask you to accept any rules. They work on the musical values that every modern citizen knows. But Scarlatti imposes his own rules. It’s like a card game. If you don’t accept the rules, you can’t play.

Scarlatti: Keyboard Sonata in F Minor, K.69/L.382/P.42

What kind of statement do you want to make with your recording?

This recording is for me like a declaration of love to this composer. I didn’t want to make anything special there: just play as clearly as possible so that the listener can form his own ideas. Here I continue my idea to give something back to the main characters on my musical path. One of them is Scarlatti. I made a big selection on purpose: to lose myself in the world of Scarlatti and to give the listeners the chance to lose themselves, too. I wasn’t interested to record once again some of the most famous sonatas – I play famous pieces only when I hear something special there what I want to share like I did with Schubert, Chopin, or Liszt. I think that Scarlatti’s music is an antidote to many issues of our time: by its wit, it can cure most of our neuroses.

In this interview, we cannot cover all the aspects of your multifaceted personality but let’s talk more about important part of your life – it’s composing. You’re actively working on it and you have composed several works that have been played in different places. How did composing come into your life?

My composing began as a natural process, going together with playing by ear and improvising. I started writing music when I decided to give shape to my own “good ideas” that I had noted in my teenage years. First, I note elements: fragments of melody, rhythm, and harmonic sequences. I keep them in a notebook and forget them for a while. Then I come back and pick up the ideas that have remained good. Ideas come like flashes. I get inspiration from anywhere: from movies, books, from melodies that suddenly come to my mind.

I have realized that the main home of my inspiration is tonal, functional music. I follow the trails of the masters I admire. My composer friend Charly Mandon did a lot to encourage me to move on in harmony skills; first I used harmony intuitively, rather unconsciously. Charly also introduced me to Jérôme Ducros and Stéphane Delplace, two living master French composers. These meetings encouraged me to follow my path.

Currently, my project is to achieve a big “opus 1” of a chamber music cycle, where I use the best ideas of my early years. I am working right now on a song cycle on Baudelaire’s poetry.

How do you see the state of new music today? Where it could or should develop?

There is something good and something bad happening today. The good thing is that composers, listeners, and performers feel more and more that musical experiments are leading to a dead end, that music is less and less pre-programmed and more and more people feel that all these “requirements” are not worth the time spent understanding them and value them.

Composers need to go back to simpler forms and tonal harmony; it’s obvious that a big change is coming. After being stuck in atonalism for a century it’s really a good thing! But – if you write tonally and think it’s already a big revolution, then it is not so. Suspended 9th chords and three-note melodies are in my opinion not the resurrection of tonal music. I am mostly frustrated by the lack of polyphony in contemporary music. Too much textures: not enough relevant notes. For the future, it would be good if composers approach the interpreters and vice versa.

Now four years after your success at the Tchaikovsky competition, you already have a decent career. When you look at what you have achieved – where do you think you are now?

It’s even hard for me to say. All these four years I never stopped. I haven’t really had time to reflect. But I am proud of what I have achieved and especially grateful for the collaborations with great musicians like Mikhail Pletnev, Gidon Kremer, Valery Gergiev, Vladimir Spivakov, Janine Jansen, Martin Fröst, Camille Thomas, Joshua Weilerstein, Jérôme Pernoo. It was not easy to deal with all of these offers after the competition, but I am really pleased with the result that I have achieved over these years.

I still have been fulfilling my teenage dreams. Many of them have already been realized, many are yet to come. A long way to go, however, I earned much confidence from these artistic achievements. To be devoted to art is still my only statement: to use it for my own ends is out of the question.

I want to continue with what I have done: to play famous works, but to be loyal to what I see in the score and to not play them in any academic way as intended. And of course, I want to continue playing works that the audience doesn’t know. There are many of these lesser-known works that are worthy of being known by the world.

Ia Remmel was born in Tallinn. She graduated at the Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre with a diploma as a pianist, a piano pedagogue and a chamber musician. Since then she has been active as a piano teacher and a culture journalist. She is currently working in the Estonian music journal as an editor. She regularly writes concert reviews and articles for different newspapers and journals in Estonia and abroad.