In search of an identity for Classical music

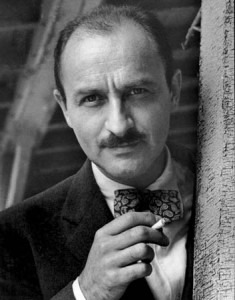

The enormous political and cultural changes that flooded Europe in the first decade of the 20th century led to a dismantling of political, social and artistic structures. As the world inexorably accelerated towards the catastrophes of World War I, composers far and wide attempted to formulate and predict the position of classical music in the modern world. Some steadfastly clung to the past, hoping to preserve the great classical traditions for the intellectual elite. Others rewrote the theoretical aspects of music to create artistic visions appropriate for their own time and culture. A third stream sought to bridge the widening gap between artist and audience and created music that had social and artistic value. At one point or another in his career, American composer Marc Blitzstein (1905-1964) connected with all three aspects of this search for musical identity.

Blitzstein was born in Philadelphia, and by age 7, he already performed a Mozart Piano concerto. He studied piano with Alexander Siloti, a student of Franz Liszt and Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky, and himself the teacher of Sergei Rachmaninoff. Fittingly, he made his professional debut with Liszt’s E-flat Piano concerto. After composition studies at the Curtis Institute of Music, Blitzstein went to Europe to further his studies with Arnold Schoenberg in Berlin. Schoenberg and Blitzstein never connected and the buddying composer went on to Paris to study with Nadia Boulanger. During these early days, Blitzstein firmly believed that true art was only for the intellectual elite. He echoed Schoenberg’s diatribe about the music of Kurt Weill’s Die Dreigroschenoper (Three Penny Opera) in his masterclass in Berlin, calling it “super-bourgeois ditties as real decadence: The dissolution of a one-time genuine article, regurgitated upon an innocent public, ready, perhaps even ripe to learn.”

By the early thirties, however, Blitzstein gradually changed his mind and came to believe that music should broaden its scope “and reach not only the select few but the masses.” In various articles and journals he attacked Igor Stravinsky, and characterized Ravel’s Bolero as “a piece whose vulgarity and cheapness are consummate, this choice opium package was not smuggled in, we got it at the hands of Toscanini and the Philharmonic.” “I have written some harsh things in the past about Kurt Weill and his music,” Blitzstein explains,“ but he hasn’t changed, I have. His almost elementary, uninhibited use of music, seemingly careless, really profoundly sensitive, predicts something new for the theatre.” Of fundamental importance to this new stream of consciousness was his relationship with the novelist and critic Eva Goldbeck. They met in 1928, and although Blitzstein was a dedicated homosexual, the couple married in 1933.

When Eva unexpectedly died in 1936, Blitzstein began work on a leftist political opera entitled The Cradle will Rock. Premiered under the direction of Orson Welles the opera was a resounding success and paved the way for a number of additional political works. He actively fought and composed during World War II, and his opera Regina played to critical acclaim on Broadway in 1949. However, his greatest commercial success came with an adaptation of Weill’s Threepenny Opera. Other theatre projects, including Reuben Reuben, Juno and the orchestral tone poem Lear: A Study have never managed to gain a foothold in the repertory. Given his outspoken leftist political orientation and acknowledged membership of the Communist Party, it was inevitable that Blitzstein was subpoenaed to appear before the “House Committee on Un-American Activities,” chaired by Senator Joseph McCarthy. Blitzstein refused to cooperate and in the end, he was not called to testify. Two final operas, Idiots First and The Magic Barrel remained unfinished as Blitzstein was murdered in Martinique in 1963. His long-time friend Leonard Bernstein wrote, “I cannot even begin to measure our loss of him as a composer. I can only think that I have lost a part of me, but I know also that music has lost an invaluable servant. His special position in music theatre is irreplaceable.”