In a previous article, Maurice Ravel as a Young Man, we followed the story of Ravel’s early life and first forays into the world of professional composition. We left off at the turn of the century, with twenty-five-year-old Ravel poised to cement his legacy.

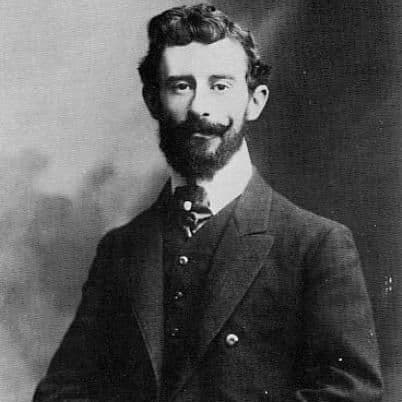

The young Maurice Ravel © debralynnmusic.org

The first few years of the 20th century were eventful and controversial for Ravel, full of genuine highs and lows. Continued institutional conflict came in the form of tensions with the traditionalist director of the Conservatoire, Théodore Dubois, and with the receipt of Ravel’s only Prix de Rome award, where he came third in composition trials for his cantata Myrrha. David Burnett James speculates that Ravel’s lack of Prix de Rome triumph was the result of two factors: firstly, Ravel may have taken certain liberties with Myrrha and failed to dot and cross all of the musical “i’s and t’s” expected by the judges, out of a certain contrarian sardonicism. After all, this was the man described by Cortot as being a “deliberately sarcastic, argumentative, and aloof young man who read Mallarmé and visited Satie.” Indeed, it was Ravel’s reputation that was likely the second factor in the judges’ withholding of the highest honours from the young composer.

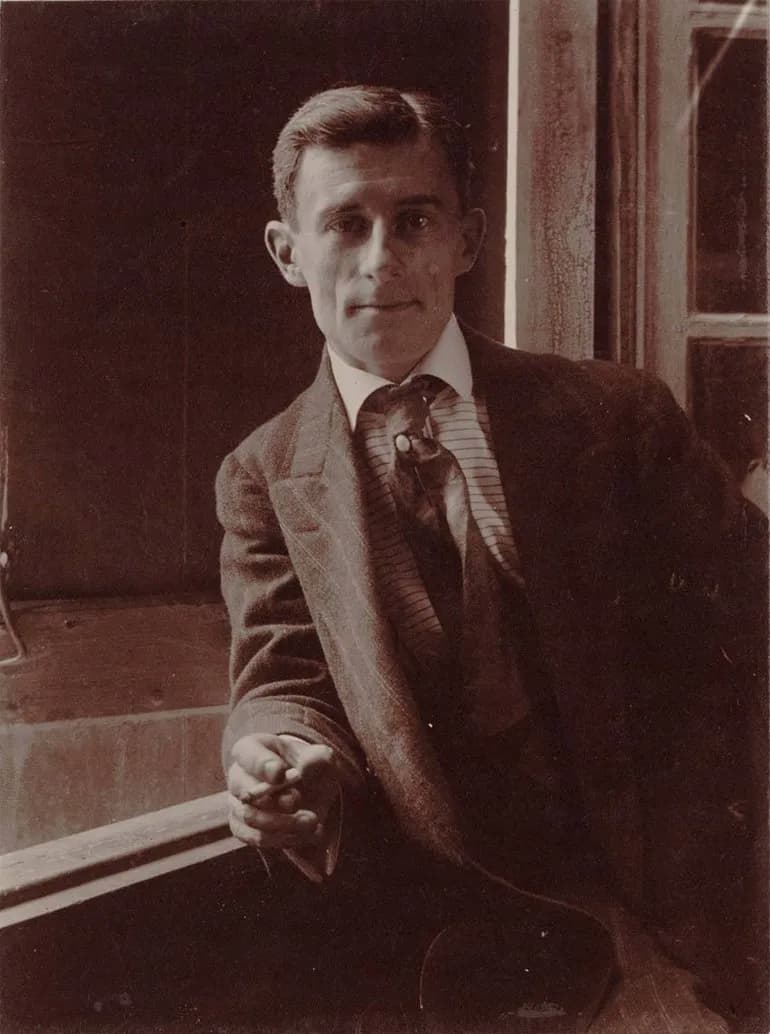

Portrait of Stephane Mallarmé, by Nadar, 1896 © Wikipedia

Elsewhere, journalist Pierre Lalo was stirring up unnecessary trouble in the press, accusing both Ravel and Claude Debussy of committing plagiarism and imitation of each other in various works. Despite the composers’ established mutual respect, Lalo’s commitment to setting the two up as competitors necessitated a certain degree of coolness and reserve in public settings. Nonetheless, Ravel had allies elsewhere, and in particular, he benefitted from a social group called the Société des Apaches, of which he was a key member from its earliest days. A group of sophisticates, artists, and poets, including pianist Ricardo Viñes, writer and critic Michel-Dimitri Calvocoressi, and Manuel de Falla, the young men ranged about the various intellectual arenas of Paris, exploring ideas and causing mischief. In and amongst these various clashes and gaieties, Ravel had moments of withdrawal and solitude, and such moments became a greater part of his personality as he aged. He himself speculated that this tendency to withdraw and hide his true feelings originated in his Basque blood, stating that Basques felt deeply – but crucially, did not show it.

Maurice Ravel: “Pavane pour une infante défunte”

The piano composition Pavane pour une infante défunte had shown Ravel’s promise and garnered him initial public success and attention, but in light of institutional clashes, he needed an undeniable coup, an irrefutable compositional achievement. In 1901, Ravel delivered this with his groundbreaking Jeux d’eau, a piano work in which decorative pianistic virtuosity was treated as an “essential ingredient” rather than “superimposed protrusions,” according to Burnett James. Inspired by Liszt’s pianism, particularly his Les jeux d’eaux à la Villa d’Este from his third suite of his Années de pèlerinage, this work began a new chapter in Ravel’s compositional treatment of the piano.

Maurice Ravel: Jeux d’eau (Andre Laplante, piano)

In the years 1902-3, Ravel began and finished his String Quartet in F major, which was premiered at the Salle de la Schola Cantorum on the 5th of March 1904. While Ravel himself spoke of the work with perfunctory detachment, commenting that the work “reflects a definite preoccupation with musical structure, imperfectly realised, no doubt,” the reception of others was more stringently positive. By some verbal accounts, Debussy himself wrote to Ravel: “In the name of the gods of music and my own, do not change one thing in your quartet.”

Maurice Ravel: String Quartet in F major

Ravel soon set about orchestrating, and in so doing creating what he called the true version of his earlier composition Shéhérazade, the song cycle with poetry by Société des Apaches member Tristan Klingsor. Suffused with the seminal Exposition of 1889 and its showcase of gamelan and other Eastern music, and inspired by the exotic imagery of Klingsor’s poetry, the young composer found a greater sensuousness and spontaneity of style in his orchestration of Shéhérazade.

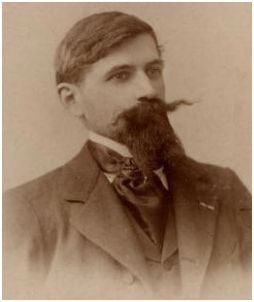

Tristan Klingsor

In 1905, Ravel made the somewhat inscrutable, and arguably unwise, decision to re-apply – for the fifth time – to the Prix de Rome. The result of this decision no individual could have possibly anticipated. Despite his stature as a celebrated composer of the Pavane, Jeux d’eau, the String Quartet, and Shéhérazade, Ravel’s submission for the preliminary round was deemed insufficiently technically accomplished for him to proceed.

With this came a wide-reaching flurry of discourse, often dubbed the “affaire Ravel.” For once, Pierre Lalo used his full journalistic powers in aid of, instead of against, Ravel, with journals such as Le Temps, Le Matin, and Le Mercure de France all expressing outrage at the perceived injustice of Ravel’s inadmission. Novelist Romain Rolland wrote a letter to Paul Léon, the director of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, showing support for Ravel in a restrained and sage manner:

“… justice compels me to say that Ravel is not simply a student of promise, he is already one of the most highly regarded of the young masters of the French school, which does not number many… Ravel submitted himself for the Prix de Rome examination not as a novice but as a composer who had already proved his mettle… it is necessary for everyone to protest a decision which… damages the true interests of justice and art.”

The indirect result of all of this furore was the resignation of the Paris Conservatoire’s conservative director, Dubois, and the hiring as his replacement Gabriel Fauré, Ravel’s former teacher and “cher maître.” This staffing change did much good for the culture and musical output of the Conservatoire. Throughout the ordeal, Ravel was silent, doing nothing to sway public opinion and issuing no statements. With Dubois’ resignation, and Ravel’s acceptance of an invitation to spend a summer travelling around Europe with friends, the affaire Ravel was closed, and he never again applied to the Prix de Rome. With the death of his father in 1908, Ravel became the notional head of the family, and with this began the decade of Ravel’s greatest creative output and activity.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter