“Music is the Language of God”

Max Bruch

Celebrating his 75th birthday in 1906, the legendary violinist Joseph Joachim declared that Germany had four great violin concertos. Among the four—of course including the superb singular efforts in this genre by Beethoven, Mendelssohn and Brahms—Joachim also included the G-minor concerto by Max Bruch (1838-1920). He even suggested that Bruch had written the richest and most seductive violin concerto of them all. Bruch composed this concerto during his time as music director to the court at Koblenz, and as we celebrate the centennial of his death in 2020, his name is still primarily associated with the G-minor concerto. Most of his other compositions, although written in the same highly personal and lyrical Romantic style, have fallen into obscurity. Critics have relegated Bruch to the status of a minor master. To be sure, Bruch was no groundbreaking- revolutionary, as his compositional style never wavered throughout his long career. He emerged on the German music scene dominated by Mendelssohn, lived under the shadow of Wagner and Brahms, and died within a decade of the first performance of Schoenberg’s Pierrot lunaire.

Joseph Joachim

Max Bruch was born in Cologne, son of a police official and a highly talented singer. In fact, he received his first musical education from his mother and started composing at the age of nine. Ignaz Moscheles immediately recognized his extraordinary musical talent, and at the age of 14 Bruch won the coveted Frankfurt Mozart-Stiftung Prize by submitting a string quartet. This enabled him to study with Ferdinand Hiller, Carl Reinecke and Ferdinand Breunung, and his first substantial work was an opera based on a Goethe Singspiel. Encouraged to travel throughout Germany, Bruch visited Leipzig and other cultural centers but decided to base himself in Mannheim. He composed his cantata Fithjof, which audiences received with great enthusiasm, followed in 1863 by his opera Loreley. The opera is based on the Rhine legend and composed to a libretto by Emanuel Geibel. Shortly before his death, even Mendelssohn contemplated a performance. After a few successful performances, brief revivals in Leipzig under the young Mahler (1887) and in Stuttgart under Pfitzner (1916), the opera disappeared from the repertory. It only resurfaced again in the late 20th century.

Max Bruch: Die Loreley Act II: Woher am dunkeln Rhein? (Lenore, Chorus) (Michaela Kaune, soprano; Prague Philharmonic Chorus; Munich Radio Orchestra; Stefan Blunier, cond.)

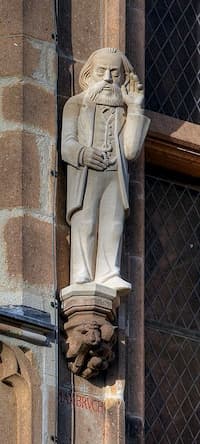

Statue of Max Bruch by Gerd Haas

After leaving his Mannheim post, Bruch visited Paris and Brussels, but eventually accepted the position of music director in Koblenz in 1865. His friendships with the violinists David, Joachim, Sarasate, and Willy Hess, inspired nine concerted works for that instrument. Bruch actually loathed the piano, calling it a “dull rattle-trap.” Instead, as he famously remarked, “the violin can sing a melody much better than a piano, and melody is the soul of music.” Following an appointment in Sonderhausen and a brief conducting engagement in Berlin, Bruch moved to Bonn and enjoyed his reputation as an eminent German composer working independently. In 1879 Bruch successfully conducted his secular oratorios Odysseus and Das Lied von der Glocke for the Philharmonic Society in Liverpool. On the strength of these two performances alongside some financial considerations, Bruch was appointed to succeed Sir Julius Benedict as conductor to the Liverpool Philharmonic Society. His time in England was somewhat turbulent, as he was unable to get along with the players who according to Bruch “had rather lax standards.” In addition, his compositions held limited appeal in the British Isles and the United States because of rising anti-Germany feelings in the buildup to World War I.

Max Bruch: Scottish Fantasy, Op. 46 (Nicola Benedetti, violin; BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra; Rory Macdonald, cond.)

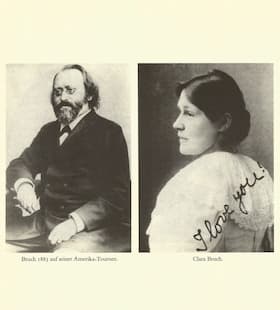

Max Bruch

Bruch left Liverpool in 1883 to become director of the Breslau Orchesterverein, where he stayed through the end of the season in 1890. Bruch spent the last decades of his life in Berlin, working as a professor of composition until his retirement in 1910, and conducting master classes until his death in 1920. He was highly respected as a teacher, with Respighi and Vaughan Williams among his students in his Berlin composition classes. Owning to his extraordinary musical talent Bruch was destined to become one of the great legacy composers. That promise remained unfulfilled, however, because he not only worked in the shadow of Brahms, but also steadfastly retained a compositional track that was based on his deep reverence for the music of Mendelssohn and Schumann. But what is more, his utter distaste and outspoken criticism of the New German School of Wagner and Liszt made him exceedingly unpopular with critics and contemporaries alike. Bruch composed more than 200 works, among them operas, symphonies, large-scale dramatic works for chorus and orchestra, and a variety of concertos. While the vast majority of his works are not currently programed, they nevertheless exude imaginative beauty, high-spirited energy, and fine workmanship.

Max Bruch: Kol nidrei, Op. 47 (Lynn Harrell, cello; Philharmonia Orchestra; Vladimir Ashkenazy, cond.)

Great music. Thanks for this Max Bruch revival.