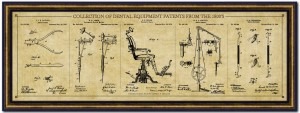

And now for something extremely painful! Imagine waking up with a severe toothache in the middle of the 19th century. In many cases, you might have to wait a couple of month before an itinerant practitioner of the dental trade actually made his way to your local community. And once he got there, his dental instruments would easily have resembled torture instruments from the dark ages. Cavity preparation prior to filling relied on rudimentary rotary excavators. The most basic dental drill was the bur and thimble. The bur was rotated between the thumb and forefinger, and the thimble, worn on the index finger, enabled pressure to be applied without a hole being drilled simultaneously in the operator’s hand. When conservative dentistry failed, dental extraction was the only option. And in the days before anesthetics, numerous variants of forceps—acting like pliers—were used to get the job done. Several types included adjusting screws to regulate the separation of the jaws, in an attempt to prevent the collapse of very carious teeth during the course of extraction. Not entirely pleasant, in any case!

And now for something extremely painful! Imagine waking up with a severe toothache in the middle of the 19th century. In many cases, you might have to wait a couple of month before an itinerant practitioner of the dental trade actually made his way to your local community. And once he got there, his dental instruments would easily have resembled torture instruments from the dark ages. Cavity preparation prior to filling relied on rudimentary rotary excavators. The most basic dental drill was the bur and thimble. The bur was rotated between the thumb and forefinger, and the thimble, worn on the index finger, enabled pressure to be applied without a hole being drilled simultaneously in the operator’s hand. When conservative dentistry failed, dental extraction was the only option. And in the days before anesthetics, numerous variants of forceps—acting like pliers—were used to get the job done. Several types included adjusting screws to regulate the separation of the jaws, in an attempt to prevent the collapse of very carious teeth during the course of extraction. Not entirely pleasant, in any case!

Little importance was attached to prevention, as general oral hygiene was reserved for the most affluent classes. Although the toothbrush had already been invented in the 17th century, very few people could actually afford this basic dental tool. General oral hygiene sets, in the most expensive cases, included toothbrushes, toothpowder boxes and scaling instruments. But the most troubling aspect of the dental trade in the mid-19th century was the fact that there were no official certifications or standards for dental practitioners. As a result, a substantial number of traveling charlatans of varying competence roamed the countryside. And one of these shady dentists, by the name of McTeague made his way into a novel by Frank Norris. Set in San Francisco during the days of the gold rush, the story of jealously, greed, violence and finally murder was published in 1899. This garish tale became the inspiration for at least three films—including Slow Burn released in 2000—and it was also adapted as an opera by William Bolcom in 1992.

McTeague is a dentist of limited intellect running a dental shop in San Francisco. His best friend Marcus brings his cousin Trina for dental work, and while McTeague fixes her teeth, he falls in love with her. Once they have declared their love for each other and are set to marry, it is discovered that Trina has won 5,000 dollars in the lottery. Marcus becomes jealous, as he feels he has been cheated out of a bride and out of the money. The marriage takes place, but Trina refuses to touch the 5,000 dollars, which she invests with her uncle. Meanwhile, the relationship between Marcus and McTeague steadily deteriorates. In one particularly brutal fight McTeague breaks Marcus’s arm, who subsequently intends to become a rancher in southern California. Before leaving San Francisco, Marcus informs the local authorities that McTeague has been practicing dentistry without a license or degree. McTeague loses his practice, and taking all of Trina’s domestic savings, abandons her. When McTeague returns destitute and a full-blown alcoholic, he demands the money from Trina’s lottery winnings. She refuses, and McTeague beats her to death. He takes all her gold and heads south towards Mexico pursued by Marcus who has join the hunt for the rogue dentist. Marcus finally catches McTeague in Death Valley, and in the ensuing struggle, Marcus is killed. As he dies, Marcus handcuffs himself to McTeague, who is now stranded and alone waiting for his own death in the arid waste of Death Valley. Now that’s the stuff for a good opera libretto, and the American composer William Bolcom engaged Arnold Weinstein and Robert Altman to versify the novel. Bolcom, in turn, fashioned an eclectic, post-modern score featuring a kaleidoscope of musical styles. Ragtime, waltzes and barbershop quartets are infused with hints of Expressionism and a whiff of Italian opera. Crossing the boundaries between high and low art, McTeague is grafting together the branches of the American operatic tradition in order to be primarily entertaining. As one critic suggested, “the story should inspire obsession, not entertainment; it demands concentration and continuity, not variety and amusement.” Nevertheless, in the early 1990’s, it was an attempt to forge a new populist direction for American opera, and it is certainly less painful than an actual visit to McTeague’s dental shop!

McTeague is a dentist of limited intellect running a dental shop in San Francisco. His best friend Marcus brings his cousin Trina for dental work, and while McTeague fixes her teeth, he falls in love with her. Once they have declared their love for each other and are set to marry, it is discovered that Trina has won 5,000 dollars in the lottery. Marcus becomes jealous, as he feels he has been cheated out of a bride and out of the money. The marriage takes place, but Trina refuses to touch the 5,000 dollars, which she invests with her uncle. Meanwhile, the relationship between Marcus and McTeague steadily deteriorates. In one particularly brutal fight McTeague breaks Marcus’s arm, who subsequently intends to become a rancher in southern California. Before leaving San Francisco, Marcus informs the local authorities that McTeague has been practicing dentistry without a license or degree. McTeague loses his practice, and taking all of Trina’s domestic savings, abandons her. When McTeague returns destitute and a full-blown alcoholic, he demands the money from Trina’s lottery winnings. She refuses, and McTeague beats her to death. He takes all her gold and heads south towards Mexico pursued by Marcus who has join the hunt for the rogue dentist. Marcus finally catches McTeague in Death Valley, and in the ensuing struggle, Marcus is killed. As he dies, Marcus handcuffs himself to McTeague, who is now stranded and alone waiting for his own death in the arid waste of Death Valley. Now that’s the stuff for a good opera libretto, and the American composer William Bolcom engaged Arnold Weinstein and Robert Altman to versify the novel. Bolcom, in turn, fashioned an eclectic, post-modern score featuring a kaleidoscope of musical styles. Ragtime, waltzes and barbershop quartets are infused with hints of Expressionism and a whiff of Italian opera. Crossing the boundaries between high and low art, McTeague is grafting together the branches of the American operatic tradition in order to be primarily entertaining. As one critic suggested, “the story should inspire obsession, not entertainment; it demands concentration and continuity, not variety and amusement.” Nevertheless, in the early 1990’s, it was an attempt to forge a new populist direction for American opera, and it is certainly less painful than an actual visit to McTeague’s dental shop!

William Bolcom: McTeague

More Anecdotes

- Bach Babies in Music

Regina Susanna Bach (1742-1809) Learn about Bach's youngest surviving child - Bach Babies in Music

Johanna Carolina Bach (1737-81) Discover how family and crisis intersected in Bach's world - Bach Babies in Music

Johann Christian Bach (1735-1782) From Soho to the royal court: Johann Christian Bach's London success story - A Tour of Boston, 1924

Vernon Duke’s Homage to Boston Listen to pianist Scott Dunn bring this musical postcard to life