No one dies at a favourable time, needless to say, but Felix Mendelssohn’s timing was particularly unfortunate. 1847 was one year before revolution would sweep across Europe, and so Mendelssohn would have his legacy formed in a post-revolutionary context. His perceived musical conservatism was distrusted, and the rise of nationalism meant that his ethnic Judaism became a prominent issue. It didn’t matter that Mendelssohn’s family had left Judaism. Nor that he, the reviver of Bach’s Matthew Passion, was a devout Lutheran. (‘Every kind of music ought, in its peculiar way, to tend to the glory of God,’ he once said.) It didn’t matter that Mendelssohn was something of a German nationalist himself. The spirit of the age was against him.

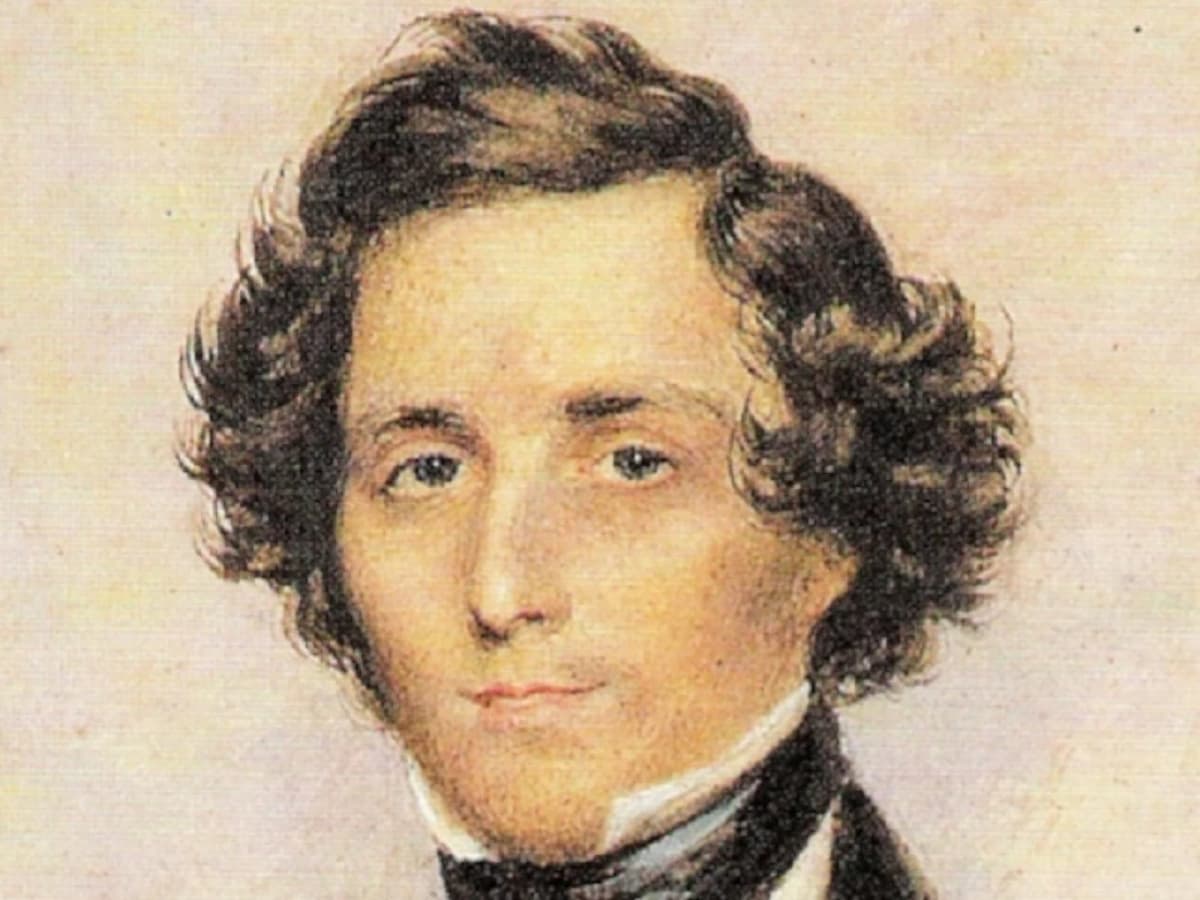

© U.S. Public Domain

Richard Wagner singled him out in his infamous Das Judenthum in der Musik (‘Jewishness in Music’), which was first published in 1850 by Franz Brendel, an influential music journalist who championed this new progressive-nationalist view of music history. Wagner wrote that Mendelssohn:

has shown us that a jew can possess the richest measure of specific talents the most refined and varied culture, the loftiest, most tender sense of honour, without even once through all these advantages being able to bring forth in us that profound, heart-and-soul searching effect we expect from music.

The full ugliness of this prejudice manifested itself in Nazi Germany. The regime literally wrote Mendelssohn out of history and Nazi thugs removed his statue from its honoured place outside St. Thomas Church, Leipzig (the church where Bach was music director). Both the evil and ridiculousness of it all was captured brilliantly in the opening chapter of the novel Mendelssohn is on the Roof by Czech-Jewish writer Jiří Weil. A group of workmen is tasked by Active Reich Protector Reinhard Heydrich with removing a statue of Mendelssohn from atop a concert hall. However, they cannot work out which statue is Mendelssohn, so they decide, in accordance with the education in racial science they have all received, to pull down the statue with the biggest nose. Unfortunately for them, it turns out to be Wagner.

Felix Mendelssohn: Symphony No. 4 in A Major, Op. 90, MWV N16, “Italian” – I. Allegro vivace (Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra; Herbert von Karajan, cond.)

Fanny and Felix Mendelssohn © Bettmann/Corbis

The criticism of Mendelssohn as superficially sentimental was not always directly, or even at all, antisemitic. It could, for example, be found in the backlash against supposed Victorian failings — shallowness, prudishness etc. — with which Mendelssohn, who had a close relationship with Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, could easily be associated. There are echoes of this in George Bernard Shaw’s criticism of Mendelssohn’s ‘kidglove gentility’ and ‘conventional sentimentality’, though Shaw also recognised that Mendelssohn was capable of both an extraordinary fire and a delicacy that deserves our admiration.

A related and perhaps more enduring criticism is that Mendelssohn’s music is insufficiently original. Although fellow composer Hector Berlioz admired Mendelssohn professionally and personally – he called him ‘enormously, extraordinary, superbly, prodigiously talented’ — he nevertheless remarked that Mendelssohn ‘is still rather too keen on composers who are dead’. Which contains some truth: he did more for the promotion of music of the past than the present, and his music is more influenced by the old than the new. Mendelssohn, for his part, had a low opinion of Berlioz’s music, regarding it as mad and messy, and even barbarous; he could be as nasty and wrong about Berlioz’s music as others were about his. Nevertheless, they got on well personally, and Berlioz conducted Mendelssohn’s music to great acclaim.

Felix Mendelssohn: String Quartet No. 6 in F Minor, Op. 80, MWV R37 – I. Allegro vivace assai (Emerson String Quartet)

© Photos.com/Getty Images

Mendelssohn was unquestionably a master of his craft – no one has ever denied him that. The criticism is usually that his music lacks depth or innovation. This has been blamed on his personal life; the musicologist Alfred Einstein wrote that ‘he had no inner forces to curb, for real conflict was lacking in his life as in his art’. Which is not quite true. Yes, Mendelssohn came from an affluent family and enjoyed various material comforts, but he nevertheless had his own personal troubles and flaws. However, he simply didn’t believe that music ought to be violently new. This view is given its fiercest expression in a letter he wrote to a friend:

I deny forthwith that there are new paths to be cleared, for there are no more new artistic territories. All of them have long since been discovered. New ground! Vexatious demon for every artist who submits to it! Never, in fact, did an artist break new ground. In the best case, he did things imperceptibly better than his immediate predecessors. Who should break the new ground? Surely no one but the most sublime geniuses? Well, did Beethoven open up new ground completely different from Mozart? Do Beethoven’s symphonies proceed down completely new paths? No, I say. Between the first symphony of Beethoven and the last of Mozart I find no extraordinary [leap in] artistic value, and no more than ordinary effect. The one pleases me and the other pleases me.

A provocative argument – and one I don’t think I agree with, as it happens – but it shows you how Mendelssohn saw musical history differently from many of his musical contemporaries and successors. I suspect this view partly has to do with his own musical development (rather than his affluence). From a very early age, he was a supreme composer and player – probably the greatest prodigy there has ever been. And so he left himself almost no room to improve, as he was already utterly brilliant, with his own clear style. This is an enviable problem to have, but a problem nonetheless. It meant that the popular narrative of struggle and development just could not be found in Mendelssohn’s life and work. Yet considered with historical distance, this fact almost makes him look radical – or at least radically different. Indeed, the passage of time has, in a long and roundabout way, worked in Mendelssohn’s favour, and since the Second World War he has regained his rightful place among the musical greats.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Steven Watson is a classical guitarist, composer and writer in the United Kingdom.

Wonderful information. THANK YOU!!!

Pleasure, thanks for reading!