Thoughts on listening to Vingt Regards sur l’enfant-Jésus

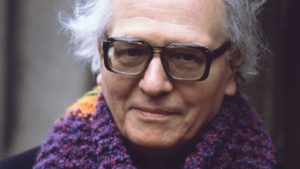

Olivier Messiaen builds cathedrals in sound. From a single candle gently flickering in a quiet side chapel to the glorious fan traceries of the main transept, the private place for solitary prayer and contemplation to the awe-inspiring painted spaces where the many gather to celebrate the glory of God, his music is monumental in its scale and breadth, a hypnotic Sainte-Trinité in sound.

And if Messiaen is the architect, then the pianist who performs his music is the guide, sometimes tenderly, sometimes violently, always colourfully leading us through the aisles and passageways, the arches and niches, past gilded icons and kaleidoscopic stained glass. The entire work takes just over two hours to perform; as a consequence it is rarely performed without an interval, but British pianist Steven Osborne, who has been playing this incredible music for almost 20 years, believes it should be played as a whole, without a break, to create “a deeper sense of engagement with the work as a whole, for both myself and the listener.”

And if Messiaen is the architect, then the pianist who performs his music is the guide, sometimes tenderly, sometimes violently, always colourfully leading us through the aisles and passageways, the arches and niches, past gilded icons and kaleidoscopic stained glass. The entire work takes just over two hours to perform; as a consequence it is rarely performed without an interval, but British pianist Steven Osborne, who has been playing this incredible music for almost 20 years, believes it should be played as a whole, without a break, to create “a deeper sense of engagement with the work as a whole, for both myself and the listener.”

Messiaen’s Vingt Regards sur l’enfant-Jésus is arguably the greatest piano work of the twentieth century. A work of immense scale, it is beautiful, voluptuous, powerful, sometimes brutal, thrilling, awestruck and awe-inspiring, ecstatic, and also intimate and deeply tender. The structure and narrative arc of the Vingt Regards is akin to Bach’s Goldberg Variations – and like Bach, Messiaen uses repeating motifs to unify the individual movements – but its drama and message, its spirituality and sense of something far greater than ourselves, is closer to one of Bach’s Passions.

It begins with a whisper, barely a heartbeat, delicate chords, softly-spoken yet vividly hued (colour is so significant to the synaesthesic Messiaen) and repeated octaves, occasionally interrupted by luminous bell sounds; a profound, introspective contemplation. And then, some 130 minutes later, it ends in a blaze of glory, bells clanging across in the keyboard in ecstasy, “all the passion of our arms around the Invisible One…” At the mid-point, the Regard de l’esprit de joie, the tenth movement, is an exuberant melding of Hindu dance rhythms with Western jazz. Here Messiaen even quotes a fragment of Gershwin’s I Got Rhythm, it’s jazzy grooviness a foretaste of the Turangalila Symphonie which was to come later.

The journey through this music is remarkable, immense, exhilarating and overwhelming. Every note, chord, phrase and gesture is freighted with meaning. Messiaen creates an extraordinary range of colours, timbres and tone, fully utilising both the modern piano’s capabilities and drawing on his own experience and appreciation of the organ, heard in particular in his distinctive chords, which are used for colour rather than strict harmonic progression. The music is replete with translucent filigree arabesques, shimmering, flickering trills, brilliant chirruping birdsong, plangent bass chords, rumbling, rolling Lisztian arpeggios…

The best performances end in silence, the great cathedral now complete, its aisles quiet, as the audience contemplates what it has heard, and experienced, as much a mark of respect to the performer who has delivered this monument to us, as to the composer and his extraordinary vision. The best performances suspend time too, and the cumulative experience of the music is so incredible that you hardly notice that some two hours have elapsed from those first hushed chords. In the Vingt Regards the rapture and ecstasy of Messiaen’s faith is captured in music which reverberates with passion, spirituality, awe and, ultimately, joy.