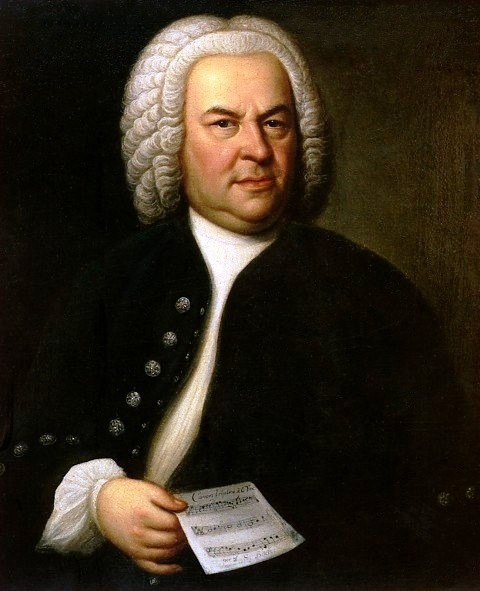

J.S. Bach

The regularized austerity of J.S. Bach’s music, in particular The Art of Fugue, has fascinated many composers. Bach’s work was left unfinished, with the final quadruple fugue (Contrapunctus XIV) started but not completed before Bach’s death.

J.S. Bach: Die Kunst der Fuge: Fuga a 3 Soggetti (Contrapunctus XIV) (Glenn Gould, piano)

The end breaks off abruptly, just as Bach left the manuscript unfinished.

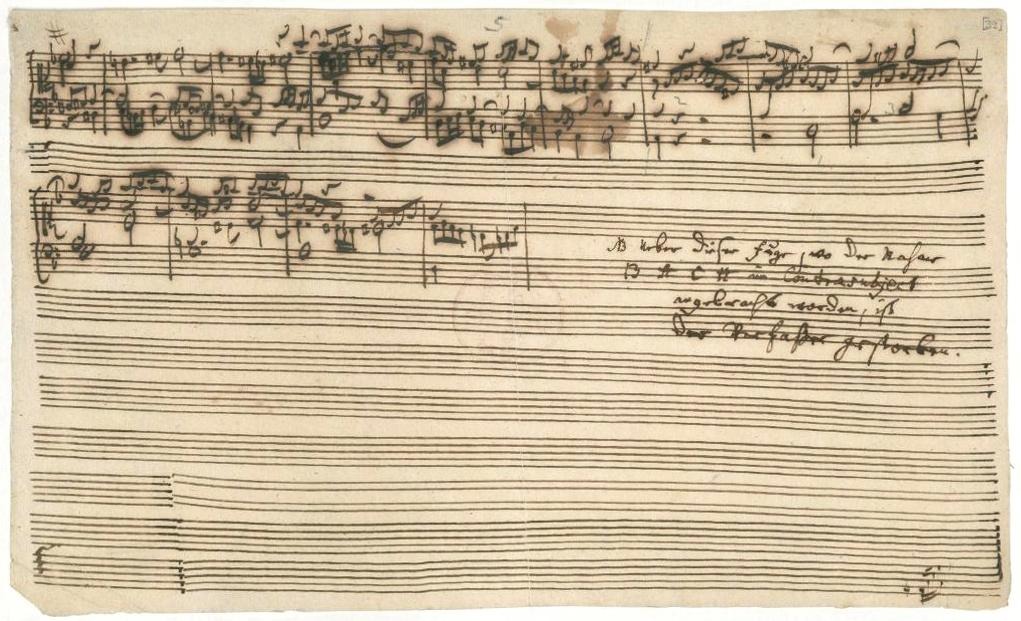

The Unfinished Fugue

The final page of this fugue ends in an incomplete measure. The writing on the page is by Bach’s son C.P.E. Bach and it says “Über dieser Fuge, wo der Name B A C H im Contrasubject angebracht worden, ist der Verfasser gestorben.” (“At the point where the composer introduces the name BACH in the countersubject to this fugue, the composer died.”) C.P.E.’s being a bit dramatic here as it is thought that this manuscript page actually dates from one or two years before his father’s death.

In 1909, Ferrucio Busoni was working on a critical edition of Bach’s great work and in 1910, after some work with the composer and theorist Bernhard Ziehn, he completed the quadruple fugue, which he entitled Grosse Fugue. What’s more important is the subtitle: A contrapuntal fantasy on J.S. Bach’s Last Unfinished Work.

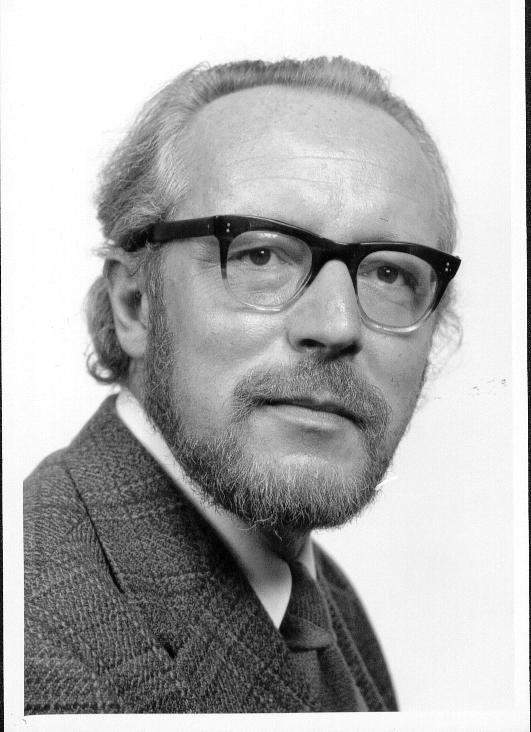

Ferrucio Busoni

Ferrucio Busoni: Grosse Fuge: I. Fuga I – Fuga II – Fuga III (Holger Groschopp, piano)

In June 1910, Busoni expanded and made a ‘definitive’ edition of his completion of Bach’s fugue under the title of Fantasia contrappuntistica, adding a ‘Preludio corale’ to the work. Busoni called this the ‘definitive’ version.

Ferrucio Busoni: Fantasia contrappuntistica – Preludio corale (Wolf Harden, piano)

Immersed as he was in the world of Bach, Busoni was still a consummate pianist and brought to his completion of the Bach work a touch of the 19th century as well – one commentator described the work as having ‘Bachian roots and Lisztian textures,’ thus enabling Busoni to not only pay homage to Bach but also to put the work into the line of history, extending it into the future.

The final fugue is a perfect example of this. The section begins in B flat minor, and the key change to D minor showcases the last subject that Bach was not able to write of his quadruple fugue. This isn’t what you would recognized from the surface as Bach but it really is a bit too austere to be anything 19th century either. The entire structure opens out so that there’s a low bass that sounds the B-A-C-H theme while above it the chorale sounds in the upper voices. The work as a whole closes on unisons Ds.

Ferrucio Busoni: Fantasia contrappuntistica: Fuga IV – Stretta (Wolf Harden, piano)

Kenneth Leighton

It was an amazing work for 1909 and, in 1956, another composer took up Busoni’s idea. Kenneth Leighton’s Fantasia Contrappuntistica, called ‘an homage to Bach,’ won the Busoni Prize for Composition and was given its premiere in Italy by Maurizio Pollini in 1956. In listening to the chorale melody, we can hear how much further Leighton has advanced upon the idea first presented by Bach and then refined by Busoni.

Kenneth Leighton: Fantasia contrappuntistica, Op. 24 – III. Chorale: Lento sostenuto – (Margaret Fingerhut, piano)

From the 1740s to 1909 to 1956, we have a time line of over 200 years where the same idea has been approached by different composers, creating very different pieces as the work passes through their hands.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter