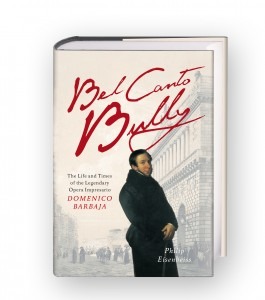

Domenico Barbaja in Naples in the 1820s

Credit: Eisenbeiss, Philip (2013). Bel Canto Bully

And yet these opera house executives are very different from the great impresarios of the late 18th and early 19th century when the term was coined. The original impresarios were not mere employees as they are today, but they were entrepreneurs who personally took on commercial and financial risk. They would assume leadership of an opera house, usually owned by local royalty or nobility, taking on the managerial responsibilities as a concessionaire. In other words, if the house under their supervision prospered, they could personally do well. If the house failed, they would be financially damaged.

Given the enormous financial burden of running an opera house, impresarios frequently went bankrupt, earning themselves a reputation as adventurers and chancers. Much of that changed with one man, who became not only extremely rich himself, but also earned sobriquets such as “King of the impresarios” or “Napoleon of the impresarios”: Domenico Barbaja (1777-1841).

Given the enormous financial burden of running an opera house, impresarios frequently went bankrupt, earning themselves a reputation as adventurers and chancers. Much of that changed with one man, who became not only extremely rich himself, but also earned sobriquets such as “King of the impresarios” or “Napoleon of the impresarios”: Domenico Barbaja (1777-1841).From impoverished background in northern Italy, Barbaja managed to amass a fortune by relying on his entrepreneurial nous, pig-headedness and commercial acumen. Initially attracted to the opera houses because they were the venue where gambling took place, he soon built a gambling empire spanning many Italian and Austrian cities. Only later did he decide to take over the responsibility and concession for the musical side of the theatres as well.

He scored his first financial triumph in 1805 at La Scala of Milan, when he successfully bid for the gambling concession and introduced roulette into the theatre’s foyer. But it was in 1809, when he took over the twin concessions of gambling and opera at the Teatro San Carlo in Naples, that he built not only his second fortune but also established himself as a first-rate talent spotter.

Given the need to constantly provide his expanding audience with new musical works, the great impresario engaged the relatively unknown Gioachino Rossini as his Music Director in Naples. For Barbaja, Rossini wrote his most important opere serie, including Elisabetta, La Donna Del Lago and Otello, laying the cornerstone for his path to becoming the most important opera composer of his time. Barbaja is also credited with discovering Vincenzo Bellini right out of the Naples conservatoire, and promoting and developing dozens of the composers of the bel canto period, including Gaetano Donizetti.

Given the need to constantly provide his expanding audience with new musical works, the great impresario engaged the relatively unknown Gioachino Rossini as his Music Director in Naples. For Barbaja, Rossini wrote his most important opere serie, including Elisabetta, La Donna Del Lago and Otello, laying the cornerstone for his path to becoming the most important opera composer of his time. Barbaja is also credited with discovering Vincenzo Bellini right out of the Naples conservatoire, and promoting and developing dozens of the composers of the bel canto period, including Gaetano Donizetti. When it came to casting singers, Barbaja was keen to keep costs under control by not hiring overpriced superstar singers. Rather, he sought to build his own stable of performers, who he kept on fixed salary under long dated contracts, while he promoted and marketed them and rented them out to other stages. Barbaja launched and represented some of the greatest singers of his generation, including Isabella Colbran, GB Rubini and Luigi Lablache. Barbaja’s unique system of artist management benefited the careers of the singers while enriching himself. An entrepreneur through and through, Barbaja also ran a construction and contracting business, and led the reconstruction of the Teatro San Carlo after it had burned to the ground in 1816.

While Barbaja was largely forgotten after his death in 1841, his legacy lives on in the dozens of bel canto masterpieces he commissioned, several spectacular buildings around Naples including the Teatro San Carlo, and countless stories of the impresario’s larger than life personality and a life of excess that would rival any Hollywood magnate.

Juan Diego Flórez: Rossini – Otello, ‘Che ascolto!’

Mariella Devia – Quel sangue versato – Roberto Devereux – 2016