Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Let’s start this little series on Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and his circle of friends with a look at the supposed relationship between Mozart and Beethoven. Biographer Otto Jahn related the following anecdote: “Beethoven… was introduced to Mozart, and played to him at his request. Mozart, considering the piece he performed to be a showpiece, was somewhat cold in his expression of admiration. Beethoven remarked this, begged for a theme for improvisation, and inspired by the presence of the master he reverenced so highly, played in such a manner as gradually to engross Mozart’s whole attention.

Beethoven Monument at Beethovenplatz, Vienna

Turning quietly to the bystanders, he emphatically said, mark that young man, he will make himself a name in the world!” It certainly is a good story, but unfortunately it is not corroborated in any contemporary documents. It might all just have been wishful thinking, and it is reasonable to assume that Mozart and Beethoven simply never met. There can be no doubt however, that Mozart’s work greatly influenced Beethoven. When Beethoven was working on his 5th symphony, he copied out a passage from Mozart’s 40th Symphony, which he subsequently adapted into his own. Similar links have been found between the C-minor piano Concerto K. 491 and Beethoven’s Third Concerto in the same key, and also the Quintet for Piano and Winds K. 452, which has a fraternal twin in Beethoven’s Op. 16.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Piano Quintet in E-flat Major, K. 452

Joseph Leutgeb

Joseph Leutgeb (1732-1811) was an outstanding horn player, and a reviewer in Paris described him as “a superior talent with the ability to sing an adagio as perfectly as the most mellow, interesting and accurate voice.” Leutgeb had joined the musical establishment in Salzburg in 1763 as a colleague of Leopold Mozart and of Konzertmeister Michael Haydn.

Natural Horn in C

He quickly made friends with the 7-year old Wolfgang, and when Wolfie was away on musical journeys he did sent greetings to Leutgeb in his letters. Once both were situated in Vienna, Leutgeb became Mozart’s favorite horn player. In fact, Mozart wrote a number of concertos for the natural horn specifically for Leutgeb’s phenomenal abilities. Documentary evidence seems to indicate that Mozart and Leutgeb had a “curiously joking relationship.” K. 417, for example, bears the mock dedication, “Wolfgang Amadé Mozart takes pity on Leutgeb, ass, ox, and simpleton, at Vienna, 27 March 1783.” Leutgeb apparently did not mind the teasing, and they enjoyed a good and lasting friendship.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Horn Concerto No. 2 in E-flat Major, K. 417 (Sebastian Weigle, horn; Dresden Philharmonic Orchestra; Jörg-Peter Weigle, cond.)

Coat of Arms of the

Thun und Hohenstein

The Thun-Hohenstein family belonged to the historical Austrian and Bohemian nobility. They were diplomats and ambassadors, statesmen and ministers, and Róża Maria Gräfin von Thun und Hohenstein is currently a member of the European Parliament. The family was always highly supportive of the arts, and they certainly belong at the head of any list of Mozart’s patrons during his last decade. Johann Joseph Anton Thun-Hohenstein, or “Old Count Thun,” as Mozart called him, invited the freshly married Mr. and Mrs. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart to be his honored guests in the city of Linz.

The Thun-Hohenstein Palace

The “Old Count” was a Freemason, and he kept an excellent private orchestra. Mozart excitedly wrote to his father, “on Tuesday November 4 [1783] I shall give an academy in the theater here, and since I have no symphony with me I am writing a new one at breakneck speed, which must be ready then.” Since the Mozarts only arrived on 30 October, that left merely five days to compose and copy-out a full-fledged symphony. Mozart, it has been suggested, may have “exaggerated for effect, as he often did, since they spent an entire month in the city.” Regardless, Mozart used the symphony again for his academy in the Burgtheater in 1784, and it was surely played by the Count’s orchestra when the Mozarts visited him in Prague palace during January 1787. The symphony became a kind of Mozart calling card, and Wolfie writes to his father “you could give it away and have it performed everywhere.”

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Symphony in C major, K. 425 (Linz) (Salzburg Mozarteum Orchestra; Hans Graf, cond.)

Silhouette of Anton Stadler

We don’t know exactly when Mozart first met the clarinet virtuoso Anton Stadler (1753-1812), but indications of their friendship date from the early 1780s. The Mozart biographer Otto Deutsch dates the first performance by Stadler of a Mozart work to 23 March 1784. On that occasion, Stadler was part of a group performing the premier of the Serenade in B-flat for 13 Instruments, K. 361. However, already in October 1781 Mozart had mentioned an exceptional clarinetist who took part in the first performance of the Serenade in E-flat, K. 375 for pairs of clarinets, horns and bassoons. “The six gentlemen who executed it,” he writes, “are poor beggars, who however, play quite well together, particularly the first clarinet and two horns.” Both Stadler and Mozart belonged to the same Masonic lodge in Vienna, and Mozart had a number of choice nicknames for him, including the “Miracle of Bohemia,” and “Nàtschibinitschibi,” a combination of “poor miser” and “man of folly.

Constanze Mozart

Constanze Mozart didn’t like Stadler at all, and she even claimed that he stole money from Mozart. She was certainly distressed to see “to what extent Mozart involved Stadler in his personal life and finances.” Regardless, Mozart was very fond of Stadler, and he was certainly impressed by his playing. He writes in 1785, “I have never heard the like of what you contrived with your instrument. Never should I have thought that a clarinet could be capable of imitating the human voice as it was imitated by you. Indeed, your instrument has so soft and lovely a tone that no one can resist it…” Stadler’s flaky personality none withstanding, his friendship with Mozart has given us some of the most sublime music imaginable.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Clarinet Quintet in A Major, K. 581 (Sabine Meyer, clarinet; Hagen Quartet)

Joseph Haydn

I don’t think that there is any doubt that Mozart and Haydn were friends. Although the relationship is not well documented, there is plenty of evidence that they enjoyed each other’s company and greatly respected each other’s work. They probably first met around 1783/84 in Vienna, and it has been suggested that they played chamber music together. Haydn did not have a shred of jealousy in his body, and he freely praised Mozart. “If only I could impress Mozart’s inimitable works on the soul of every friend of music,” he writes, “and the souls of high personages in particular, as deeply, with the same musical understanding and with the same deep feeling, as I understand and feel them, the nations would vie with each other to possess such a jewel.” Mozart in turn, had the highest admiration for Haydn.

Mozart statue at Burggarten, Vienna

An early biographer related the following anecdote: “At a private party a new work of Haydn was being performed. A number of musicians were present, and the one standing next to Mozart found fault with one thing after another. Mozart listened patiently for a while, and when the faultfinder conceitedly declared ‘I would not have done that,’ Mozart retorted: Neither would I, because neither of us could have thought of anything so appropriate.” Most famously and stylistically was influenced by Haydn’s Opus 33 string quartets, Mozart wrote his six “Haydn” quartets during the early years of their friendship. Haydn’s response to Leopold Mozart upon hearing the works for the first time is legendary. “Before God and as an honest man I tell you that your son is the greatest composer known to me either in person or by name.”

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: String Quartet No. 18 in A Major, K. 464 (Esterhazy Quartet)

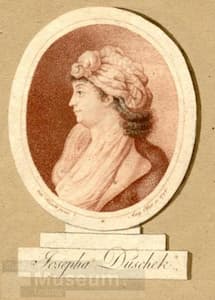

Josepha Dušek

She was born Josepha Hambacher in Prague on 6 March 1754. After marrying her music teacher František Xaver Dušek, she embarked on a long and highly successful career as a freelance singer. Her voice was praised for its range and flexibility, and “she was also appreciated for her musicianship, and superb execution of both bravura arias and recitatives.” Josepha Dušek gave the first performance of the dramatic aria Ah, perfido! Op. 65 by Beethoven in 1796, and since her mother Maria Domenica Colomba hailed from Salzburg, she visited the city in 1777. She met Mozart at that time, and he was suitably impressed to compose for her the recitative and aria Ah, lo previdi, K. 272. That relationship seems to have gotten a lot closer after Mozart’s success with The Marriage of Figaro in 1786. During his 1787 visit in Prague, Mozart wrote the concert aria “Bella mia fiamma, addio,” K. 528. Mozart’s son Karl Thomas relates the following anecdote: “One day, Frau Duschek slyly imprisoned Mozart, after having provided ink, pen, and notepaper, and told him that he was not to regain his freedom until he had written an aria for her… Mozart submitted himself, but to avenge himself for the trick Frau Duschek had played on him, he used various difficult to sing passages in the aria, and threatened to destroy the aria if she could not succeed in performing it at sight without mistakes.” It seems that Josepha succeeded in that particular task; maybe she even succeeded in seducing Mozart as well?

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: “Bella mia fiamma, addio,” K. 528 (Christiane Oelze, soprano; Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach Chamber Orchestra; Hartmut Haenchen, cond.)

Mannheim Palace

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart first met the oboist Friedrich Ramm (1744-1813) in Mannheim in 1777. Suitably impressed by Ramm’s playing, Mozart apparently couldn’t remember the oboist’s name. As he relates to his father “the oboist whose name I have forgotten but who plays very well and has a delightfully pure tone. I have made him a present of my oboe concerto and the fellow is quite crazy with delight.” Ramm was indeed delighted as he performed the concerto no less than five times in two weeks. The work caused a veritable sensation, and Mozart, finally remembering the soloist’s name, described it as “Ramm’s cheval de bataille.” Ramm’s abilities were truly impressive, as he had been appointed to the court orchestra when he was only 14 years of age. And he took full advantage of the new and improved oboe, which had extended range and permitted performers to play the upper register with greater clarity and robust intensity. Mozart met up with Ramm again 4 years later, and specifically wrote the Oboe Quartet, K. 370 for him during his work on Idomeneo.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Oboe Concerto in C Major, K. 314 (Lucas Macias Navarro, oboe; Orchestra Mozart; Claudio Abbado, cond.)

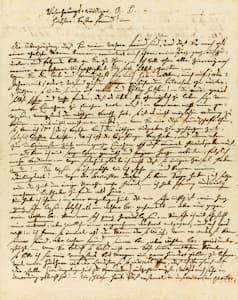

Johann Michael von Puchberg

The textile merchant Johann Michael von Puchberg (1741-1822) is remembered as a friend of Mozart who lent him considerable sums of money. Both Mozart and Puchberg were Freemasons, and when Mozart found himself in dire straits in 1788, he wrote a series of “begging letters,” of increasing desperate tone. In all, 21 letters from Mozart to Puchberg asking for loans have survived. In June 1788 Mozart wrote, “I have now opened my whole heart to you in a matter which is of the utmost importance to me; that is, I have acted as a true brother. But it is only with a true brother that one can be perfectly frank. And now I look forward eagerly to your reply, which I do hope will be favorable… I take you to be a man who will like myself certainly assist a friend, if he be a true friend, or his brother, if he be indeed a brother.”

Mozart’s letter to Puchberg

Mozart’s tone changed to desperation the following year: “Good God! I would not wish my worst enemy to be in my present position. And if you, most beloved friend and brother forsake me, we are altogether lost, both my unfortunate and blameless self and my poor sick wife and child.” Mozart apparently thanked his sponsor by composing, amongst other works, the String Trio in E-flat, K. 563. Finally, in 1791 Mozart’s financial situation had slightly improved and he began to repay his loans. Following his death, Constance who made money from memorial concerts and publications was finally able to pay the loan in full.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Divertimento in E-flat Major, K. 563 (Trio Oreade)

Antonio Salieri

First things first, Antonio Salieri (1750-1825) did not cause Mozart’s death. He was a serious and steady man, but there is also mention of him as friendly and cheerful. The Irish singer Michael Kelly assures us that Salieri “would make a joke of anything.” One thing for sure, when the 25-year old Mozart established his base in Vienna, Salieri was already a well-respected star. In fact, Salieri was one of the most important musical personalities in the city. Leopold Mozart, however, highly resented the special place Salieri held in the courts, and he openly spoke of several “cabals” of Italians led by Salieri who were actively putting roadblock into the way of Wolfie obtaining certain posts or staging his operas.” Wolfgang writes to his father in 1783, “You know those Italian gentlemen; they are very nice to your face! Enough, we all know about them. And if Da Ponte is in league with Salieri, I’ll never get a text from him, and I would love to show what I can really do with an Italian opera.”

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

In 1781 Mozart applied for the position of music teacher to the Princess of Württemberg, but Salieri got the job instead. “Salieri and his tribe will move heaven and earth to put it down,” Leopold Mozart wrote to his daughter. Then and now, Salieri has gotten some seriously bad press, but there is no real evidence of a contentious relationship between the two composers. For one, they even composed a cantata for voice and piano together, and Salieri was instrumental in leading a number of Mozart works to their successful premier, including the Symphony No. 40 in G minor. Mozart was ambitious and suspicious, and he certainly wanted Salieri out of the way, and not the other way around.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Symphony No. 40 in G minor, K. 550 (Orchestra of the 18th Century; Frans Brüggen, cond.)

Johann Christian Bach by Thomas Gainsborough, 1776

Young Wolfie Mozart would certainly have qualified for some serious frequent flier miles. Leopold immediately knew that his son represented a unique talent and opportunity, and they busily visited the courts and musical centers of Western Europe. Already in 1764, we find them first in Paris and subsequently in London. The British capital was under the spell of Johann Christian Bach, the youngest son of Johann Sebastian.

Mozart as a child, 1763

Wolfgang received musical instructions from Bach, and Nannerl Mozart reports. “Herr Johann Christian Bach, the Queen’s teacher, took Wolfie between his legs, the former played a few bars, and the other continued, and in this way they played a whole sonata, and someone not seeing it would have thought that only one man was playing.” After a mere four weeks under Bach’s mentorship Wolfie showed remarkable progress and growth as a composer. Leopold wrote, “what he had known when he left Salzburg is nothing compared with what he knows now; it defies the imagination … right now, Wolfgang is sitting at the harpsichord playing Bach’s trios.” When Mozart said farewell to his friend Johann Christian and England, he carried with him a substantial parcel containing music by the “London Bach.” In 1772, at Leopold’s urging, Mozart transcribed some of these compositions into the “Pasticcio” piano concertos, K. 107.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Piano Concerto in D-major, K. 107/1 “after J.C. Bach” (Gerrit Zitterbart, piano; Schlierbacher Chamber Orchestra; Thomas Fey, cond.)