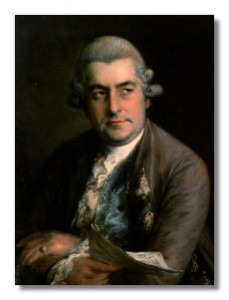

CPE Bach

credit: http://www.naxos.com/

After a mere four weeks in England, Wolfi showed remarkable progress and growth as a composer. Leopold wrote, ”what he had known when he left Salzburg is nothing compared with what he knows now; it defies the imagination … right now, Wolfgang is sitting at the harpsichord playing Bach’s trios.” Much of this progress is rightfully attributed to Johann Christian’s musical instruction, an activity that was wholeheartedly supported by Daddy Leopold. However, Johann Christian also functioned as Wolfi’s mentor. Nannerl reports, “Herr Johann Christian Bach, the Queen’s teacher, took Wolfi between his legs, the former played a few bars, and the other continued, and in this way they played a whole sonata, and someone not seeing it would have thought that only one man was playing.” This mentoring relationship took on special importance during the period Leopold fell ill. And it has been rightfully suggested that J.C. Bach played a crucial role in Wolfi’s pivotal transition from childhood to adulthood. In fact, J.C. Bach received the same kind of mentorship from his own half-brother, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach. When J.S. Bach passed away in 1750, J.C. was a mere teenager. It was quickly decided that he should live with his brother C.P.E. in Berlin, and taking along three harpsichords he had inherited from his father, J.C. arrived in 1750. C.P.E. had already been in the service of Frederick the Great for an extended period of time and was universally acknowledged as one of Europe’s leading performers and composers. What is more, his keyboard treatise “Versuch über die wahre Art das Clavier zu spielen (An Essay on the True Art of Playing Keyboard Instruments) revolutionized didactic instruction and laid the foundation for the keyboard methods of Muzio Clementi and Johann Baptist Cramer. His compositional oeuvre includes, among numerous others, hundreds of Keyboard Sonatas and Keyboard Concertos. Under C.P.E. Bach’s guidance, J.C. became an accomplished performer and interpreter. He certainly would have performed a number of C.P.E. Bach’s Keyboard works, among them the E-Major Concerto, H. 417.

Carl Phillipp Emanuel Bach: Keyboard Concerto in E Major, Wq. 14, H. 417

JC Bach

credit: http://www.classical.net/

Yet J.C. was not content to become a mere performer but also showed some promise as a composer. Under C.P.E. Bach’s guidance, he fashioned a number of early piano concertos and several sets of keyboard Sonatas. Although of a predominantly light character, Leopold Mozart wrote in a letter to his son, “The small thing is great, when it is written in a naturally fluent and light style and when it is efficiently put in a composition. To compose in this way is more difficult than to write all the artificial and incomprehensible harmonic progressions and hardly performable melodies…This distinguishes the master from the bungler.” Of particular importance to Mozart’s musical development, and simultaneously disclosing the indebtedness to his brother C.P.E, was a set of keyboard Sonatas J.C. published under his Op. 5.

Johann Christian Bach: “Piano Sonata in D-major, Op. 5, No. 2”

When Mozart said farewell to England, he carried with him a substantial parcel containing music by J.C. Bach, including the three Opus 5 sonatas. In 1772, Mozart transcribed these sonatas into the “Pasticcio” piano concertos, K. 107. In all probability, these transcriptions served an education purpose that was encouraged by this father. This supposition is substantiated by the autograph manuscripts as they feature “Wolfi’s handwriting in the string parts and Leopold’s notation in the figured bass and keyboard parts.” Wolfi basically retained all aspects of rhythm, melody, harmony and accompaniment, however, he did insert four tutti sections that repeat or introduce Bach’s melodic motives.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: “Piano Concerto in D-major, K. 107/1 after J.C. Bach”

Mozart

credit: http://en.wikipedia.org/

A couple years earlier, Mozart had already arranged a couple of “Pasticcio” Concertos, most famously his K. 40, which combines three solo piano pieces by Leontzi Honauer, Johann Gottfried Eckard and Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach. Mozart had met the first two composers between 1763 and 1766 during his visits to Paris, and used the first movement from Honauer’s 1763 “Six Sonates pour le Clavecin,” and the slow movement from Eckard’s 1764 collection “Six Sonates pour le Clavecin”, respectively. The concluding “Prestissimo” originates in C.P.E.’s collection “Musikalische Mancherley”, published in 1762. Wolfi held C.P.E. in the highest esteem and wrote in a letter, “he is the father, we are the boys. Those of us who can do things right have learnt to do so from him.”

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: “Piano Concerto No. 3 in D major, K. 40”

With these exercises in concerto composition Wolfi clearly prepared the way for a number of original keyboard concertos, and in the next episode we shall look at the continuing and lasting influence of J.C. Bach’s piano concertos.