In last month’s article I focused on the relationships between musicians, artists and writers in 19th century Russia, which foreshadowed the even more drastic changes of the beginning of the 20th century. Not only would the artists and painters, associated with the Arts and Crafts movement at the Abramtsevo colony, emphasize a return to Russian roots, but composers such as Mily Balakirev, César Cui, Modest Mussorgsky, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and Alexander Borodin (called the Mighty Handful — in Russian: Ϻогучая кучка) aimed at producing specifically Russian-inspired music, rather than imitating the Western European music traditions which were taught at the Conservatories of Music.

In last month’s article I focused on the relationships between musicians, artists and writers in 19th century Russia, which foreshadowed the even more drastic changes of the beginning of the 20th century. Not only would the artists and painters, associated with the Arts and Crafts movement at the Abramtsevo colony, emphasize a return to Russian roots, but composers such as Mily Balakirev, César Cui, Modest Mussorgsky, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and Alexander Borodin (called the Mighty Handful — in Russian: Ϻогучая кучка) aimed at producing specifically Russian-inspired music, rather than imitating the Western European music traditions which were taught at the Conservatories of Music.

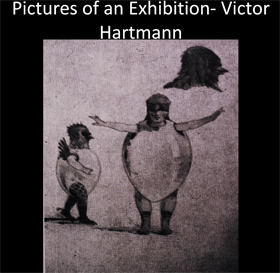

Pictures at an Exhibition (orch. M. Ravel)

X. The Great Gate of Kiev

All of these composers were self-trained amateurs. In their compositions, they included Russian village songs, Cossack and Caucasian dances, liturgical chants in the old Slavonic Church tradition and the tolling of church bells — e.g., in Ravel’s orchestration of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, we hear Russian church bells at the end of The Great Gate of Kiev. The use of church bells became almost a cliché in Russian music, but Russian bells have a special musicality which is unlike the sound of any other bells. The Russian ringers strike the different bells directly with hammers, or by using short cords attached to clappers. This creates a sort of counterpoint, but with dissonances resulting from the resounding echoes of the bells. The Western technique of ringing bells, i.e. swinging them from long ropes, makes such synchronization all but impossible.

All of these composers were self-trained amateurs. In their compositions, they included Russian village songs, Cossack and Caucasian dances, liturgical chants in the old Slavonic Church tradition and the tolling of church bells — e.g., in Ravel’s orchestration of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, we hear Russian church bells at the end of The Great Gate of Kiev. The use of church bells became almost a cliché in Russian music, but Russian bells have a special musicality which is unlike the sound of any other bells. The Russian ringers strike the different bells directly with hammers, or by using short cords attached to clappers. This creates a sort of counterpoint, but with dissonances resulting from the resounding echoes of the bells. The Western technique of ringing bells, i.e. swinging them from long ropes, makes such synchronization all but impossible.

Sadko: Hindu Song (arr. Kreisler)

The ‘Mighty Handful’ composers adopted a series of harmonic devices, creating a distinctive ‘Russian’ style, in their use of the whole tone scale, the pentatonic scale, and the diminished or octatonic scale, which was used, for example, by Rimsky-Korsakov in Sadko. In their compositions, phrases often seem to shift quite naturally from one tonal center to another, ending in a different key, creating a feeling of elusiveness, a lack of definition or logical progression in the harmony, making Russian music sound very different from the tonal structures of the West.

The ‘Mighty Handful’ composers adopted a series of harmonic devices, creating a distinctive ‘Russian’ style, in their use of the whole tone scale, the pentatonic scale, and the diminished or octatonic scale, which was used, for example, by Rimsky-Korsakov in Sadko. In their compositions, phrases often seem to shift quite naturally from one tonal center to another, ending in a different key, creating a feeling of elusiveness, a lack of definition or logical progression in the harmony, making Russian music sound very different from the tonal structures of the West.

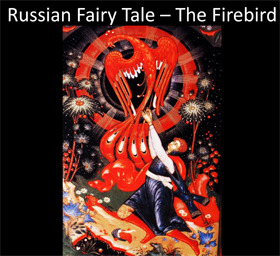

Orientalism (as seen in Balakirev’s Tamara, based on a beautiful poem by Mikhail Lermontov, in Borodin’s Prince Igor and in Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade) also became one of the best-known aspects of Russian music, introduced to the West during the Russian Seasons (Les Saisons Russes) – and was considered a typical trait of the Russian national character. The ‘Mighty Handful’s’ influence reached well into the 20th century, especially in the works of the Russian composers Sergei Prokofiev, Igor Stravinsky, and Dimitri Shostakovich, as well as those of the French composers, Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel. Debussy, in particular, would make use of the pentatonic scale and Russian Church Slavonic chants in his compositions, capturing the Russian musical spirit.

In our discussion of Diaghilev and his Ballets Russes (Interlude, June 2013) and specifically of Diaghilev’s publication ‘Mir iskusstva’ (World of Art), we had focused on his attempt to introduce modern concepts in literature, art and dance to the Russian public. As Pushkin, Turgenev, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky and Gogol had inspired the previous generation, the new generation of young artists at the turn of the century not only wanted to educate the public, but, inspired by the social and political upheaval, also wanted to create a new society. When the Bolsheviks stormed the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg, business as usual continued on nearby Nevsky Prospekt, with the city’s intense intellectual and artistic life continuing unabated, even at that perilous moment. Russian poetry attained an unprecedented beauty with the brilliant symbolism of Alexander Blok, the anguished verses of Vladimir Mayakovsky, the scintillating and feminine strength of Anna Akhmatova, and the romantic exoticism of Nikolai Gumilev — all enriching poetry with new images and rhythms.

In our discussion of Diaghilev and his Ballets Russes (Interlude, June 2013) and specifically of Diaghilev’s publication ‘Mir iskusstva’ (World of Art), we had focused on his attempt to introduce modern concepts in literature, art and dance to the Russian public. As Pushkin, Turgenev, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky and Gogol had inspired the previous generation, the new generation of young artists at the turn of the century not only wanted to educate the public, but, inspired by the social and political upheaval, also wanted to create a new society. When the Bolsheviks stormed the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg, business as usual continued on nearby Nevsky Prospekt, with the city’s intense intellectual and artistic life continuing unabated, even at that perilous moment. Russian poetry attained an unprecedented beauty with the brilliant symbolism of Alexander Blok, the anguished verses of Vladimir Mayakovsky, the scintillating and feminine strength of Anna Akhmatova, and the romantic exoticism of Nikolai Gumilev — all enriching poetry with new images and rhythms.

| If you were music, I would listen to ceaselessly And my low spirits would brighten up. | If you were a star, I would gaze by the window till dawn, And peace would enter my soul….. |

Anna Akhmatova – March Elegies

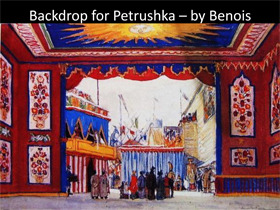

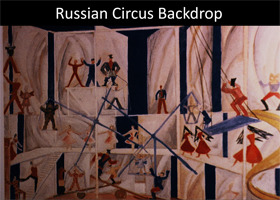

The new ballet productions’ set designers, such as Alexandra Exter (also a painter), now rejected illusory scenery and began using neutral structures that ‘came to life’ only in the interaction with dancers. Structured, vertical groupings, such as the landings and stairs of functional stage installations, were reminiscent of the multiple levels of acrobatic performances in the Russian circus. No longer were ballet presentations descriptive or illustrative, developing content or character, but instead evoked the more subtle nuances of an emotional condition by means of dance.

The new ballet productions’ set designers, such as Alexandra Exter (also a painter), now rejected illusory scenery and began using neutral structures that ‘came to life’ only in the interaction with dancers. Structured, vertical groupings, such as the landings and stairs of functional stage installations, were reminiscent of the multiple levels of acrobatic performances in the Russian circus. No longer were ballet presentations descriptive or illustrative, developing content or character, but instead evoked the more subtle nuances of an emotional condition by means of dance.

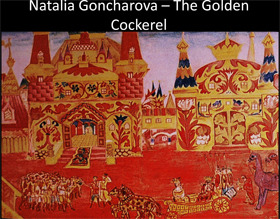

Similar interests were expressed by other artists at the time. The pioneering Modernism of Russia’s painters, Alexandra Exter, Natalia Goncharova, Liubov Popova, Olga Rozanova, Kasimir Malevich, Vasily Kandinsky, Marc Chagall and Naum Gabo represented an ambition to discover new bases of artistic creation. Neo-Primitivism, Cubism, Futurism, Suprematism were part of this exploration of a ‘new’ language, with the artists always hoping to affect the new society they saw on the horizon – all of them deeply disappointed when Stalin came to power and art was forced to turn towards ‘Soviet realism’. Many of the ‘modern’ artists were silenced, disappeared in the Gulags of the Soviet Union, or emigrated when possible — and one of the most creative, stimulating and adventurous periods of the arts in Russia had come to an end.