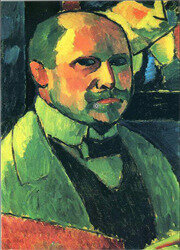

Alexej von Jawlensky (1864-1941)

During the period leading up to the war, many intellectuals, artists, musicians and writers in Germany and Austria supported the prospect of war as proud patriots, and like their French counterparts, volunteered for military service in astonishing numbers. However, the regimes of the dual Austro-Hungarian monarchy, with its aging Emperor Franz-Joseph – which had on one hand its ‘Biedermeier’ (“ordinary, simple citizen”) mentality and on the other, the ‘Ringstreet’s’ pompous grandeur (see my previous article on the Secession in Vienna) — and the Prussian militaristic, extremely class-conscious society around Kaiser Wilhelm in Germany, were seen by most of the intellectuals and artists as corrupt, stultified and outdated. Thus there was an anti-monarchical/anti-institutional component to their orientation, unlike in republican France. Many of their publications, such as ‘Die Jungen’ (The Young Ones) in Vienna and ‘Der Sturm’ (The Storm) in Berlin expressed these sentiments, in which war was seen as catharsis, liberating language and art. Even one of the most respected literary authorities in Europe at the time, Thomas Mann, said ‘that the hearts of poets were inflamed as soon as war was declared’. Words like, ‘fatherland’, ‘battle’, ‘war’, ‘action’ became part of the vocabulary of various art associations and of the younger generation in revolt against their elders, demanding new artistic freedom and expression, a remake of society. These sentiments were not only expressed in Austria and Germany, but they also found their counterparts in Russia with the ‘Acmeism’ (Akhmatova and Mandelstam) and the ‘Constructivsm’ and ‘Suprematism’ movements around Malevich, Popova and many others, which also welcomed the ‘revolution’ as a possibility for the creation of a ‘new’ man, a ‘new’ society. In Italy similar calls came from the ‘Futurist’ movement around Marinetti, Boccioni, Balla and Severini. All wished for liberation — their battle cry: ‘out with the old order and in with the new’ — and so in 1914, they thought that war provided the impetus for just such a change.

August Macke (1897-1914)

Part I: Orchestral Prelude

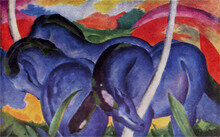

In 1911, Franz Marc, August Macke, Ludwig Kirchner, Gabriele Münter had founded ‘Der Blaue Reiter’ (a group of German Expressionist painters) along with the Russians Alexey von Jawlensky and Wassily Kandinsky. The composer Arnold Schönberg had met Kandinsky earlier that year; the two became very close friends, inspiring each other’s work. Four of Schönberg’s own paintings were shown with the Blaue Reiter group, and Kandinsky created his ‘Impression III’ painting after hearing Schönberg’s compositions ‘Pierrot Lunaire’ and ‘Gurre Lieder’. The Blaue Reiter association dissolved with the outbreak of the war in 1914. Now classified as enemy aliens, Jawlensky and Kandinsky had to leave Germany — Kandinsky first left for Russia and then for neutral Switzerland. Many other artists and intellectuals who opposed the war, such as Hermann Hesse, Albert Einstein, Stefan Zweig, Franz Werfel, Else Lasker-Schüler amongst others, had also sought refuge in Switzerland, which had become not only a haven for the opponents of the war, but also home to the supporters of the International Peace Movement, in concert with the activities of the French pacifist, Romain Rolland.

Franz Marc (1880-1916)

Rainer Maria Remarque’s ‘Im Westen Nichts Neues’ (‘All Quiet on the Western Front’ – the more disturbing literal translation is “In the West Nothing New”) appeared in 1929, about ten years after the conclusion of World War I. Remarque’s account follows the war as seen through the eyes of an ordinary soldier, conscripted with his classmates, filled at first with the euphoria of battle and comradeship, but soon disillusioned when confronted with the seemingly senseless death of so many compatriots. The few that did survive the carnage would be the “Lost Generation”, unable to fit into ordinary life after the war, never being able to forget the horror they had experienced.

Franz Marc – Fate of Animals

Piano Suite, Op. 25

III. Intermezzo

Otto Dix – Central Panel of War

Tryptich 1914-1918

The Great War had left indelible marks on a generation of musicians, artists and writers. The initial intellectualized image of war as a facilitator of internal cultural/political change faded in the face of the reality of carnage and destruction.