Henri Dutilleux: Timbres, espace, mouvement (ou, La nuit étoilée)

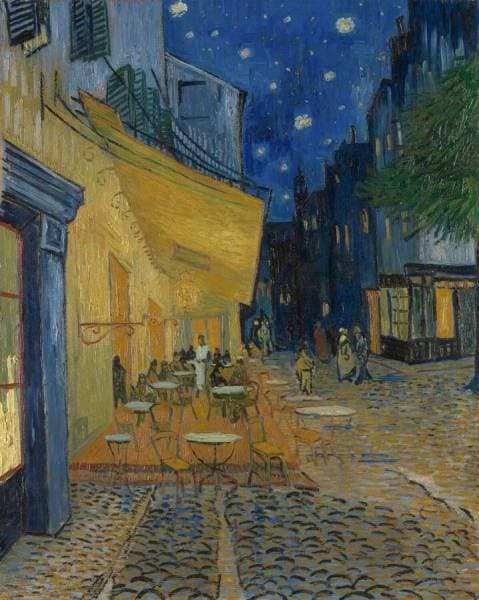

In the late 1880s, the sky at night was a point of inspiration for Vincent Van Gogh. In September 1888, he depicted a café at night in the middle of the city of Arles. Painting at night, he found that colours had a different appearance than during the day and that light had a different effect.

Van Gogh: Caféterras bij nacht (Place du Forum), c. 16 September 1888 (Terrace of a café at night (Place du Forum)), 1888 (Otterlo : Rijksmuseum Kröller-Muller)

After that foray into night painting, Van Gogh then painted the stars, even more prominent, and with a recognizable Big Dipper in the middle, shown over the river Rhône. Entitled Starry Night, better known as Starry Night Over the Rhône, this was yet another forerunner to his later starry night image.

Van Gogh: Starry Night, September 1888 (Paris: Musée d’Orsay)

The stars blaze in the sky, matched by the lights from shore reflected in the shimmering water. Although the lights promise people, we only see a man and a woman in the bottom right corner populating the image.

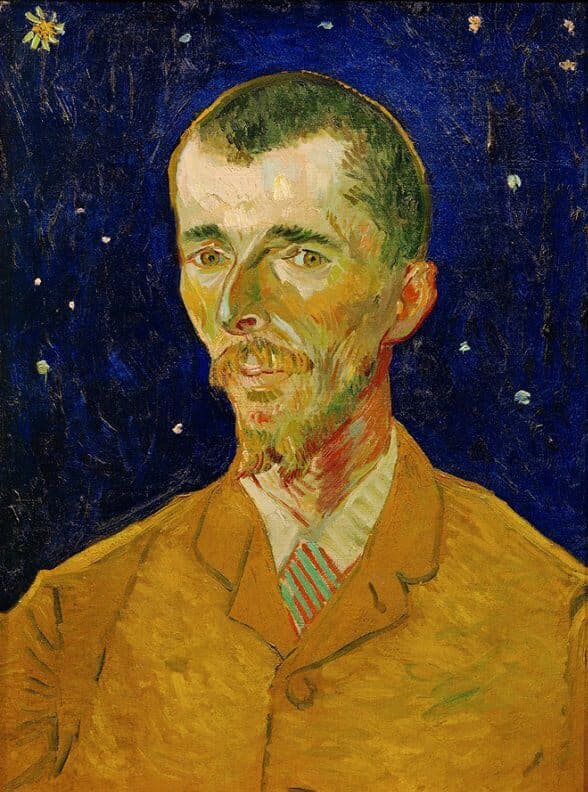

In his last painting of September 1888, van Gogh painted a picture of a new acquaintance, the Belgian painter Eugène Boch. Describing him to his brother Theo, Vincent wrote: ‘I very much like the looks of this young man with his distinctive face, like a razor blade, and his green eyes’. Behind the blond man, Van Gogh deliberately positioned a night sky, painted ‘the most intense blue I can create’ so that Boch would appear ‘like a star in the depths of an azure sky.’ Van Gogh called the portrait The Poet and it hung for a time in his bedroom in Arles.

Van Gogh: Eugène Boch, September 1888 (Paris: Musée d’Orsay)

Having gotten his desire for painting at night out of his system, Van Gogh returned to it again the next year for the work that is described as his ‘magnum opus’.

Van Gogh: The Starry Night, 1889 (New York: Museum of Modern Art)

No longer do we have recognizable constellations, now all the stars are in motion, not merely glowing but putting out coronas of light, some wheeling through the sky like comets. The cypress tree just pushes us up into the activity. Even in the sleeping town below (no lights to be seen), the olive trees seem to roil and coil to match the motion above them.

French composer Henri Dutilleux (1916–2013) wrote Timbres, espace, mouvement (ou, La nuit étoilée) on commission for the National Symphony Orchestra of Washington, DC. The three movements of the piece are not a musical version of the image, but rather the composer’s response to the painting. Dutilleux considered the painting to be ‘an enormously powerful and disturbing masterpiece’ and tried to write music that depicted what he felt from the painting, ‘a longing for the infinity of Nature’.

The first movement, Nébuleuse (Nebula), picks up on the motion of the stars above.

Henri Dutilleux: Timbres, espace, mouvement, “La Nuit étoilée” – I. Nébuleuse (Lille National Orchestra; Darrell Ang, cond.)

The second movement is a brief interlude that leads directly to the last movement, Constellations. The original work only consisted of two movements, and the Interlude, scored for 12 cellos, was added in 1991.

Henri Dutilleux: Timbres, espace, mouvement, “La Nuit étoilée” – II. Interlude – (Lille National Orchestra; Darrell Ang, cond.)

Henri Dutilleux: Timbres, espace, mouvement, “La Nuit étoilée” – III. Constellations (Lille National Orchestra; Darrell Ang, cond.)

The score is unusual for its orchestration: no violins or violas, and extra woodwinds (five flutes, four instruments of the oboe family including an oboe d’amore, four clarinets, three bassoons and a contrabassoon). The percussion used in the work includes a battery of metallic instruments.

Dutilleux takes us to a different place than other musical programs based on this painting. He captures, instead, the mystery of the painting – what if we did as Van Gogh imagined and took a train to the stars? He said that the only way to board that train was by death, but we know that we can go there on the magical carpet of his painting.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter