The Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) in Boston was founded in 1870 with most of its initial collection coming from the Boston Athenaeum, where the Museum was housed. With over 450,000 items in its collection, it’s one of the largest collections in the US. For this museum trip, we’re going to look at a few items that aren’t paintings or drawings, starting with a large table.

This console table, designed to fit against a wall, is made of porcelain and is the only known piece of porcelain furniture from the Alcora Manufactory in Spain. Alcora was a royal factory, and it is thought that this piece may have been intended for a ‘porcelain room,’ similar to the one commissioned by King Carlos III for his palace at Aranjuez. The figures on the four legs are all different, the back two figures having some kind of straight wind instrument and the front two figures with instruments that bend around the body. This was to keep them from being broken off by passers-by. In the archives of the factory are orders for matching wall plaques, small figures on brackets, and a ceramic chandelier, but their whereabouts are currently unknown. Musical instrument playing table supports are not very common. The gold instruments make a nice contrast with the tin glazing on the piece.

Alcora Manufactory: Console Table, ca. 1761-63 (MFA)

Antonio Vivaldi: Concerto for 2 Trumpets in C Major, RV 537 – I. Allegro (Gabriele Cassone and Matteo Frige, trumpets; Ensemble Pian and Forte; Francesco Fanna, cond.)

Meissen Manufactory was the first European company that figured out hard-paste porcelain. Originating in China in the 7th or 8th century, it was one of China’s principal exports and fetch very high prices in Europe. The German mathematician, physicist, physician, and philosopher Ehrenfried Walther von Tschirnhaus did the early experiments in 1708 that led to the founding of the royal factory at Meissen in 1710. This cup and saucer carry the coats-of-arms of the Da Ponte and Pisani-Gambara families of Venice. On the cup a set of 4 figures, including a flutist and a stringed instrument player, makes music and on the saucer, a flutist plays for a dancing or promenading couple. In the middle ground are other figures walking and working and in the background, bordering a large lake, is a building with an orange roof.

Meissen Manufactory: Cup and Saucer for the Da Ponte and Pisani-Gambara families,

ca. 1753 (MFA)

Mauro Giuliani: Grand Potpourri, Op. 53 (Norbert Kraft, guitar; Nora Shulman, flute)

In this 18th century ivory and paper fan, a girl plays a tambourine with trailing ribbons, a couple dances to the sound of a flute and, at the centre, a young woman sits in a bower. Below, in the centre section, a young man whizzes by in his cabriolet, a light, two-wheeled carriage. On the reverse, gondolas and sea-going ships are in the top part, while the centre section has a Chinese-style tower. This fan comes from around 1755 from France or Germany and would have fit the hand of any fashionable young lady.

Cabriolet Fan, ca. 1755 – front (MFA)

Cabriolet Fan, ca. 1755 – back (MFA)

Arcangelo Corelli: Sonata in F Major, Op. 5, No. 10 – I. Preludio: Adagio (Enrico Casularo, flute; Andrea Coen, harpsichord)

In this section of a tapestry depicting the seven liberal arts, Music (MUSIQUE) sits enthroned with a small organ at her side. With her left hand she plays the organ and with her right hand, she traces the notes in a music manuscript that is held by an attendant. Behind the organ is a man pumping air so it will sound. In front of her sits a well-dressed minstrel playing a dulcimer and a small child plays a horn. On the right of Music’s throne are other musicians, playing a variety of instruments including a small harp, a lute, a recorder, a flute, and a rebec. Half-hidden in middle of them is a small child playing a triangle with jangles attached. At the extreme right is a jester and his bagpipes. The whole ensemble is set in a garden with a trellis at the back and a trellis-arch on the right.

Tapestry from the Seven Liberal Arts series: Music, first quarter of 16th century (MFA)

Michael Praetorius: Terpsichore: Pavane de Spaigne (Ensemble Mezzo)

In this etching by Luca van Leyden, an old couple playing a rebec and lute harmonize into their old age. Intended to be an allegory on a long-lasting harmonious marriage, the act of playing music is also a testimony to the pleasures of music as one gets old. The choice of instruments is curious because women are rarely shown playing bowed string instruments.

Lucas van Leyden: The Musicians, 1524 (MFA)

J.S. Bach: Lute Partita in E Major, BWV 1006a – III. Gavotte en Rondeau (Yasunori Imamura, lute)

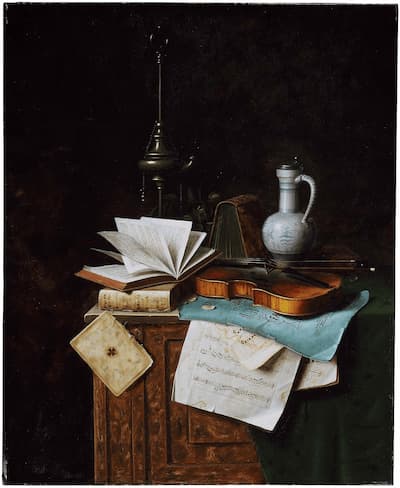

As we’ve seen in other collections, Vanitas Still Life paintings include instruments as emblems of transience. This painting by Cornelis Gijsbrechts is a virtual catalogue of symbols of transience in the 17th century: a skull, a dying candle, a soap bubble, and a violin. Dying wheat, an overturned hourglass, and a crumpled letter are more testimony. The tankard, unless its metaphor is how quickly it’s emptied, is a little less clear. The artist has also included a reminder of the transience of art, in that top right corner of the painting is coming loose from its backing – a brilliant trompe-l’oeil effect in a painting about the cost of time.

Cornelis Gijsbrechts: i, ca. 1667-68 (MFA)

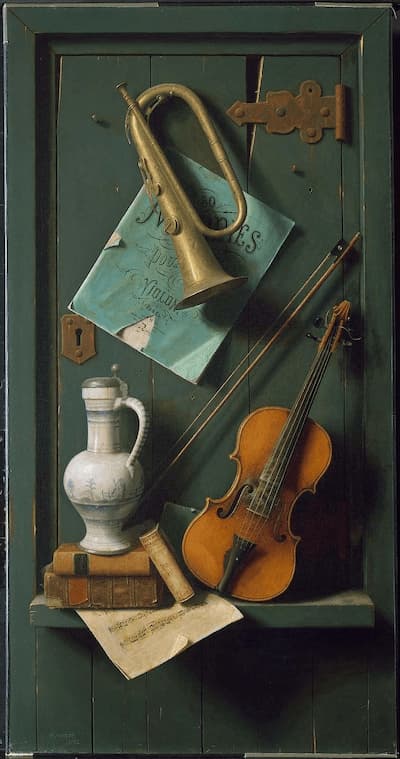

A more modern version of a still life was perfected by Irish-American artist William Harnett. His trompe-l’oeil paintings are carefully crafted towards a single idea, in this case, the theme Old Models. For him as an artist, the instruments in this painting had appeared in earlier paintings. For the 19th century viewer, this was an image of past times: the keyed bugle had been supplanted by the keyed trumpet and the violin shows its hard use in the rosin marks on the body of the instrument between the bridge and the fingerboard. Behind the bugle is a torn copy of 50 mélodies pour violon and the music under the books is the sentimental Irish ballad ‘Tis the Last Rose of Summer’ from Moore’s Irish Melodies. The books are yellowed and torn, the wood is splintered on the door and several hooks hang empty – truly old models indeed.

William Harnett: Old Models, 1892 (MFA)

Thomas Moore: Irish Melodies, Volume 5 – No. 4. ‘Tis the Last Rose of Summer (John Elwes, tenor; Yoshio Watanabe, fortepiano)

This same violin can be seen in the article on The Met in Harnett’s Still Life: Violin and Music. It also appears in Harnett’s earlier painting Still Life with Violin. Harnett, who died of kidney disease age 44, believed the instrument to be a Guarneri and it was described in his estate sale as: ‘Cremona Violin . . . “Joseph Guarnerius, fecit. Cremona, anno 1724” . . . procured by Mr. Harnett at a great cost from a celebrated collection in Paris.’ You’ll also recognize the blue and white jug as common to both paintings.

William Harnett: Still Life with Violin, 1885 (MFA)

Lorenzo Pagans, a singer, guitarist, and composer from Spain, made his name in the salons of 1860s Paris. In this picture of Pagans performing, Edgar Degas has also captured his banker father, Auguste, listening to the music. Behind him is a piano and his head is framed by the sheet music on the music stand. The picture feels very immediate, as though it had only taken a second to capture, almost like a photograph. Yet, at the same time, we have a line moving down through picture from Pagans’ eyes to Auguste Degas’ eyes to the invisible next listener in the room.

Edgar Degas: Degas’s Father Listening to Lorenzo Pagans Playing the Guitar, ca. 1869-1872 (MFA)

Lorenzo Pagans: Malagueña

The MFA collection is rich in other musical images but even in these works, we see how music is used to augment an otherwise plain table, give personality to a woman’s fan, give life to a cup and saucer, and in the various still life paintings, give us pause to think about time and mortality.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter