Pope Gregory I (540—604) was something of a religious superstar during his days. A talented administrator who initially served as a prefect of Rome, he eventually managed to establish papal supremacy. This doctrine assured supreme and universal power over the whole Church, and “universal power in the care of souls.” In fact, Gregory I was more powerful than the emperors of Rome, and he re-established papal authority in Spain and France, and sent missionaries to England. However, Gregory I is primarily known for completely reorganizing and revising the Roman worship, contributing to the development of the “Divine Liturgy.” Not surprisingly, he was known throughout the Middle Ages as “the Father of Christian Worship.” He was canonized immediately after his death, and he is still the patron saint of musicians, singers, students, and teachers.

Pope Gregory I (540—604) was something of a religious superstar during his days. A talented administrator who initially served as a prefect of Rome, he eventually managed to establish papal supremacy. This doctrine assured supreme and universal power over the whole Church, and “universal power in the care of souls.” In fact, Gregory I was more powerful than the emperors of Rome, and he re-established papal authority in Spain and France, and sent missionaries to England. However, Gregory I is primarily known for completely reorganizing and revising the Roman worship, contributing to the development of the “Divine Liturgy.” Not surprisingly, he was known throughout the Middle Ages as “the Father of Christian Worship.” He was canonized immediately after his death, and he is still the patron saint of musicians, singers, students, and teachers.

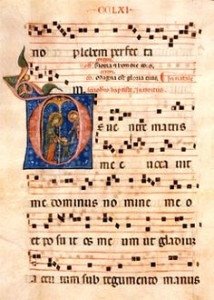

If you are surprised by his patronage of musicians and singers, you really shouldn’t be. After all, he gave his name to a large body of monophonic and unaccompanied sacred songs of the western Roman Catholic Church, known as “Gregorian chant.” In popular iconography, the “Holy Spirit” in the shape of a dove happily sings heavenly tunes into the ear of the church reformer. Of course, the chants did not originate with the dove or with Gregory I, but the pope did organize and standardize this large repertory of music to accompany his liturgical and monastic reforms. At a later date, Gregorian chant was organized into a theoretical framework to describe the tonal structure of this repertory. And the result was a pitch organization—basically musical scales with various placements of whole-tone and half-tone steps—known as “Gregorian modes,” or simply as “church modes.”

If you are surprised by his patronage of musicians and singers, you really shouldn’t be. After all, he gave his name to a large body of monophonic and unaccompanied sacred songs of the western Roman Catholic Church, known as “Gregorian chant.” In popular iconography, the “Holy Spirit” in the shape of a dove happily sings heavenly tunes into the ear of the church reformer. Of course, the chants did not originate with the dove or with Gregory I, but the pope did organize and standardize this large repertory of music to accompany his liturgical and monastic reforms. At a later date, Gregorian chant was organized into a theoretical framework to describe the tonal structure of this repertory. And the result was a pitch organization—basically musical scales with various placements of whole-tone and half-tone steps—known as “Gregorian modes,” or simply as “church modes.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: “Et incarnatus est” from “Credo” of Missa Solemnis

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov: Neapolitan Song, Op. 63

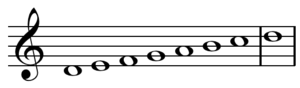

Around the late 8th century, theorists recognized 8 modal categories, subdivided into authentic and plagal modes. The distinction is not difficult to understand, as authentic melodies have the final note as the lowest pitch of the scale. In plagal modes, meanwhile, the range is extended to the interval from a fourth below to a fifth above the final note. The four authentic modes are Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian and Mixolydian, while the plagal varieties are correspondingly named Hypodorian, Hypophrygian, Hypolydian, and Hypomixolydian. So much for the initial theoretical bits, but let’s look at the characteristic placement of half steps in the “Dorian Mode.” In the modern Dorian mode, also called the “Russian minor scale” by Balakirev, the half steps fall between the second and third, and the sixth and seventh notes of a diatonic scale. Just imagine playing a scale on the white keys of the piano from “D” do “D.” In terms of sound, you actually get the equivalent of a natural minor scale. Throughout the centuries, this turned out to be a rather popular scale; have a listen to compositions by J. S. Bach, Ludwig van Beethoven, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, and from the popular folk repertory.

Around the late 8th century, theorists recognized 8 modal categories, subdivided into authentic and plagal modes. The distinction is not difficult to understand, as authentic melodies have the final note as the lowest pitch of the scale. In plagal modes, meanwhile, the range is extended to the interval from a fourth below to a fifth above the final note. The four authentic modes are Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian and Mixolydian, while the plagal varieties are correspondingly named Hypodorian, Hypophrygian, Hypolydian, and Hypomixolydian. So much for the initial theoretical bits, but let’s look at the characteristic placement of half steps in the “Dorian Mode.” In the modern Dorian mode, also called the “Russian minor scale” by Balakirev, the half steps fall between the second and third, and the sixth and seventh notes of a diatonic scale. Just imagine playing a scale on the white keys of the piano from “D” do “D.” In terms of sound, you actually get the equivalent of a natural minor scale. Throughout the centuries, this turned out to be a rather popular scale; have a listen to compositions by J. S. Bach, Ludwig van Beethoven, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, and from the popular folk repertory.

Johann Sebastian Bach: Dorian Toccata and Fugue

Scarborough Fair