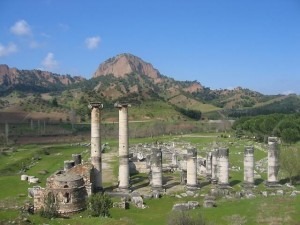

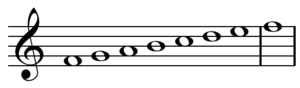

Ancient Greek philosophy described the physical world in terms of four elements: earth, air, fire, and water. Health and spiritual wellbeing depended on a balance of four bodily fluids or temperaments. Phlegmatic temperament was associated with water, choleric with fire, sanguine with air and melancholic with earth. In some of the earliest therapeutic uses of music, the Greeks used certain melodies to amplify or weaken these temperaments and thereby influence the spiritual state of an individual. Specifically, the Lydian Mode, which corresponded to the sanguine element of air, had the ability to inspire optimism, friendliness, laughter and love. The name of this mode derived from the ancient kingdom of Lydia, situated in Anatolia, and the characteristic sound emerges as the result of a raised fourth scale degree in a major scale.

Ancient Greek philosophy described the physical world in terms of four elements: earth, air, fire, and water. Health and spiritual wellbeing depended on a balance of four bodily fluids or temperaments. Phlegmatic temperament was associated with water, choleric with fire, sanguine with air and melancholic with earth. In some of the earliest therapeutic uses of music, the Greeks used certain melodies to amplify or weaken these temperaments and thereby influence the spiritual state of an individual. Specifically, the Lydian Mode, which corresponded to the sanguine element of air, had the ability to inspire optimism, friendliness, laughter and love. The name of this mode derived from the ancient kingdom of Lydia, situated in Anatolia, and the characteristic sound emerges as the result of a raised fourth scale degree in a major scale.

Lydian Mode

Throughout the entire winter of 1824/25 Beethoven was struggling with a serious intestinal disorder, which he increasingly feared might be fatal. With help from his doctor, who ordered him to avoid alcohol and coffee, Beethoven eventually recovered. In the event, this brush with death inspired one of his most profound and deeply personal musical utterances. The third movement of his String Quartet Op. 132 carries the inscription “Song of Thanksgiving to God for recovery from illness in the Lydian mode.” One of the greatest movements Beethoven ever wrote it strongly resonates with an entry he scribbled in his notebook during his time of illness. He writes, “for God, time absolutely does not exist.”

Throughout the entire winter of 1824/25 Beethoven was struggling with a serious intestinal disorder, which he increasingly feared might be fatal. With help from his doctor, who ordered him to avoid alcohol and coffee, Beethoven eventually recovered. In the event, this brush with death inspired one of his most profound and deeply personal musical utterances. The third movement of his String Quartet Op. 132 carries the inscription “Song of Thanksgiving to God for recovery from illness in the Lydian mode.” One of the greatest movements Beethoven ever wrote it strongly resonates with an entry he scribbled in his notebook during his time of illness. He writes, “for God, time absolutely does not exist.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: String Quartet No. 15 in A minor, Op. 132 “Molto adagio”

A child prodigy, Alexei Stanchinsky publically performed his first compositions at the age of 6! He was slated to become one of the musical greats, however, he suffered from a rather serious nervous disposition. We don’t know if his delusional episodes—apparently an hereditary form of dementia—were responsible for his Prelude in the Lydian Mode, but we do know that he was found dead next to a stream at age 26. His death is still a mystery, and much of his music remains unknown and unrecorded.

A child prodigy, Alexei Stanchinsky publically performed his first compositions at the age of 6! He was slated to become one of the musical greats, however, he suffered from a rather serious nervous disposition. We don’t know if his delusional episodes—apparently an hereditary form of dementia—were responsible for his Prelude in the Lydian Mode, but we do know that he was found dead next to a stream at age 26. His death is still a mystery, and much of his music remains unknown and unrecorded.

Alexei Stanchinsky: Prelude in the Lydian Mode

Anton Bruckner wrote a number of shorter choral works for liturgical use. His setting of the gradual Os justi was composed in 1879 and dedicated to Ignaz Traumihler. Traumihler was a leading proponent of the Cecilian movement that sought to reform church music. Appropriately written in the Lydian mode, the motet ends with a plainchant Alleluia.

Anton Bruckner: Os justi

The Lydian mode features prominently in Moravian folk-song. It is therefore hardly surprising that Bohuslav Martinů, who was born close to the Moravian border, already uses this mode in his earliest compositions. Each movement of his Les Rondes, originally entitled Moravian Dances, is infiltrated by the Lydian mode.

Bohuslav Martinů: Les Rondes (Moravian Dances)

Charles-Valentin Alkan was once considered one of the greatest composers for the piano. His publications, however, did not convince Robert Schumann who labeled them “false and unnatural.” When Alkan was passed over for a position at the Conservatoire, he isolated himself from the general musical life of Paris for the next 25 years. His 12 Etudes, Op. 35 were published in 1847 and the fifth study titled “Allegro barbaro” is a ferocious piano study in the Lydian Mode.

Charles-Valentin Alkan: 12 Etudes, Op. 35, No. 5 “Allegro barbaro”