In the world of the ancient Greece philosophers, music could greatly affect the mood and character of an individual. In fact, this “ethos of music,” as it was called, even made a person more or less fit for a particular job. Soldiers, for example, should listen to music in Dorian or Phrygian modes to make them stronger, and avoid music in Lydian, Mixolydian or Ionian modes, because it would turn them into cowards. “For the musical modes,” Plato writes, “differ essentially from one another, and those who hear them are differently affected by each. Some of them make men sad and grave, like the so-called Mixolydian; others enfeeble the mind, like the relaxes modes; another again, produces a moderate or settled temper, which appears to be the peculiar effect of the Dorian; and the Phrygian inspires enthusiasm.” Over the centuries, emotions and specific characteristics associated with individual modes have undergone various changes, but for the Phrygian mode the attributes mystic, vehement and leading us to sober contemplation seem to have retained currency.

In the world of the ancient Greece philosophers, music could greatly affect the mood and character of an individual. In fact, this “ethos of music,” as it was called, even made a person more or less fit for a particular job. Soldiers, for example, should listen to music in Dorian or Phrygian modes to make them stronger, and avoid music in Lydian, Mixolydian or Ionian modes, because it would turn them into cowards. “For the musical modes,” Plato writes, “differ essentially from one another, and those who hear them are differently affected by each. Some of them make men sad and grave, like the so-called Mixolydian; others enfeeble the mind, like the relaxes modes; another again, produces a moderate or settled temper, which appears to be the peculiar effect of the Dorian; and the Phrygian inspires enthusiasm.” Over the centuries, emotions and specific characteristics associated with individual modes have undergone various changes, but for the Phrygian mode the attributes mystic, vehement and leading us to sober contemplation seem to have retained currency.

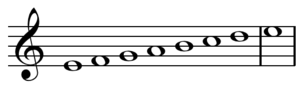

Medieval theorists applied the name “Phrygian” to the third of its eight church modes. Starting on “E” the half steps are located between the first and second, and the fifth and sixth note of the scale.

The distinctive musical quality of the Phrygian mode has resonated with composers throughout the ages. J.S. Bach certainly shocked the Leipzig congregation in 1724 with his cantata setting Aus tiefer Not schrei ich zu dir (From deep despair I cry out to you) BWV 38. Bach takes the archaic severity of the Lutheran hymn—cast in the Phrygian mode—and places it in a modern and expressive framework by using chromatic inflections and unusual harmonic progressions.

The distinctive musical quality of the Phrygian mode has resonated with composers throughout the ages. J.S. Bach certainly shocked the Leipzig congregation in 1724 with his cantata setting Aus tiefer Not schrei ich zu dir (From deep despair I cry out to you) BWV 38. Bach takes the archaic severity of the Lutheran hymn—cast in the Phrygian mode—and places it in a modern and expressive framework by using chromatic inflections and unusual harmonic progressions.

Johann Sebastian Bach: Aus tiefer Not schrei ich zu dir, BWV 38 “Chorus”

Anton Bruckner treats the Phrygian mode in his Sixth Symphony as a third force alongside major and minor tonality. It is the juxtaposition of the key of A Major and Phrygian mode that generates the central tonal argument.

Anton Bruckner: Symphony No. 6 in A Major, “Maestoso”

For Ralph Vaughan Williams, a melody by Thomas Tallis from the English Renaissance furnished the foundation for a work for string orchestra. Cast in the “Third Mode Melody,” the Tallis tune in the Phrygian mode dates from 1567 and was dedicated to the Archbishop of Canterbury. When Vaughan Williams edited the English Hymnal in 1906, he was enchanted by this ancient tune and fashioned his Tallis Fantasia. The work was first performed on 10 September 1910 at Gloucester Cathedral.

For Ralph Vaughan Williams, a melody by Thomas Tallis from the English Renaissance furnished the foundation for a work for string orchestra. Cast in the “Third Mode Melody,” the Tallis tune in the Phrygian mode dates from 1567 and was dedicated to the Archbishop of Canterbury. When Vaughan Williams edited the English Hymnal in 1906, he was enchanted by this ancient tune and fashioned his Tallis Fantasia. The work was first performed on 10 September 1910 at Gloucester Cathedral.

Ralph Vaughan Williams: Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis

In the hands of Miles Davis, the Phrygian mode also made its way into contemporary jazz. The 1960 album Sketches of Spain presents compositions largely derived from the Spanish folk tradition.

Gil Evans/Miles Davis: Sketches of Spain, “Solea”

“A work of unparalleled grace and lyricism,” it is the Phrygian mode that accounts for the delicious and distinctive ethnic flavor. Phrygian Gates, a 1977 work by minimalist composer John Adams is based on a repetitive structure that rapidly shifts between Phrygian and Lydian modes. According to Adams, “it is in the form of a modulating square wave with one state in the Lydian mode and the other in the Phrygian mode.” Join us next time when we look at compositions prominently inspired by Lydian mode.

John Adams: Phrygian Gates