In popular culture, King Henry VIII (1491–1547) is primarily remembered for his six wives and countless mistresses. His private life was summarized in a popular rhyme.

King Henry VIII,

To six wives he was wedded.

One died, one survived,

Two divorced, two beheaded.

Meynnart Wewyck: King Henry VIII

Henry had a severe disagreement with Pope Clement VIII, as he wanted his marriage to his first wife Catherine of Aragon annulled. Since the Pope wouldn’t hear of it, Henry appointed himself “Supreme Head of the Church of England” and dissolved convents and monasteries. He also invested heavily in the foundation of the Royal Navy, essentially establishing England as a modern state. And while most paintings depict Henry as a fat and middle-aged despot, he had held much promise as a young man. In fact, he was admired throughout Europe, with the Venetian Ambassador writing in 1515, “He speaks French, English and Latin, and a little Italian, plays well on the lute and harpsichord, sings from books at sight, draws the bow with greater strength than any man in England, and jousts marvelously.”

Henry VIII: “Alas, what shall I do for love?” (Alamire; David Skinner, cond.)

A portrait of Catherine Parr, sixth and last wife of Henry VIII of England

Henry was originally groomed for the Church, and his education included instruction in music. Once he ascended the throne in 1509 music occupied a prominent place in life at court. “It played a part in ceremonies of all kinds: meetings of heads of state, processions, banquets, tournaments and so on. Thus, at his coronation banquet, there was a stage on which there were some boys, some of whom sang, and others played the flute, rebeck and harpsichord.” We know that he amassed a huge and valuable collection of instruments and that he employed a number of exceptional court musicians. Henry’s leading court musician was William Cornysh, Master of the Children of the Chapel Royal. By 1547 Henry had assembled 58 musicians, including a substantial number of foreign talent. Henry apparently greatly enjoyed making music, and a contemporary writes, “the King himself practiced the organ day and night.” Besides the organ, he played the lute and he was known to sing and dance as well.

Henry VIII: “Pastime with Good Company” (Oxford Camerata; Jeremy Summerly, cond.)

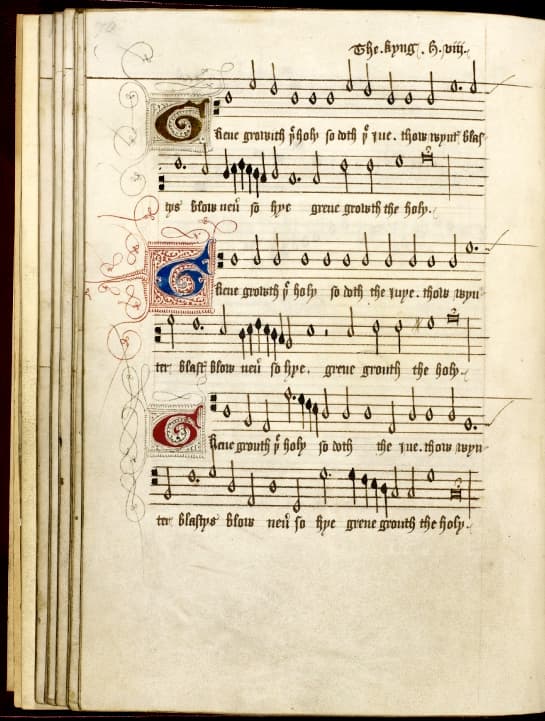

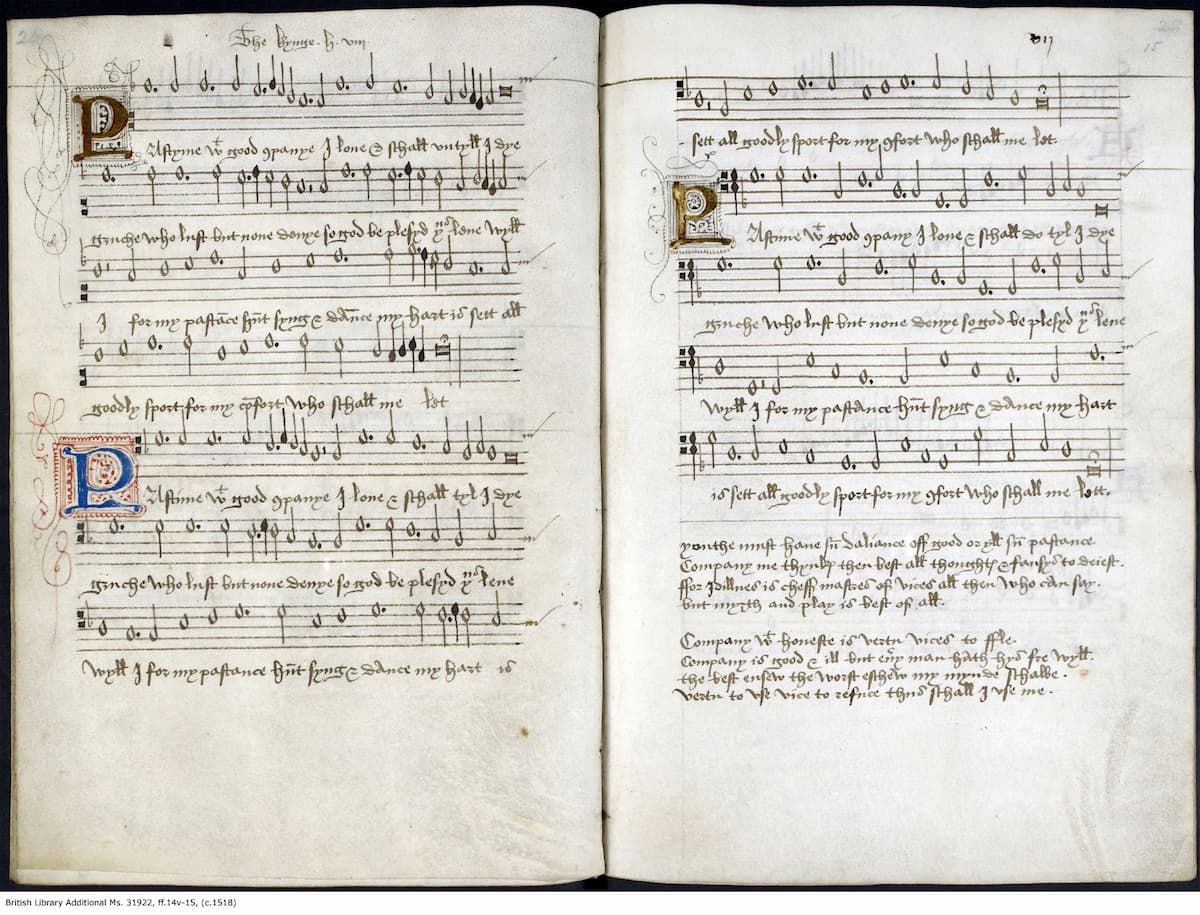

The Henry VIII manuscript

And let’s not forget that Henry VIII was also a composer. “His achievements may have been exaggerated by his subjects and posterity, but he left far more pieces than any other British monarch, though in some cases works attributed to him may be arrangements of, or additions of one or more parts to, an existing piece.” Edward Halle claimed in 1510 that Henry set two masses in five parts, “which were sung often times in his chapel, and afterwards in diverse other places.” That particular information can’t be verified, as these masses have been lost. A significant number of his compositions, however, are found in the so-called “Henry VIII Manuscript.” That name does not mean that the manuscript actually belonged to Henry, but it seems to have been compiled by someone close to him. It apparently “reflects the lively music-making at Henry’s court, with some pieces in the manuscript linked to topical events.”

Henry VIII: Departure is my chef payne (Hugh Wilson, tenor; Sirinu)

King Henry VIII: Pastime with Good Company, c. 1513

A total of thirty-four compositions are attributed to the King in the Henry VIII manuscript, “encompassing an impressive variety of song and instrumental styles.” Scholars have suggested “the texts of Henry’s songs reflect his chivalric and kingly concerns, the game of love which dictated court etiquette, and moralizing over the balancing of youthful pastimes with the responsibilities of good governance.” Several of his compositions have connections with continental music, but “their survival is no doubt due more to the celebrity of the composer than to their musical merits.” Celebrations at court were frequent and lavish, and we have an account of the 1515 May Day festivities at Greenwich. “In the wood were bowers filled purposely with singing birds which caroled most sweetly, and in one of these bastions or bowers were some triumphal cars, on which were singers and musicians, who played on organ, lute and flutes for a good while, during a banquet which was served in this place.” The same manuscript also contains 13 un-texted pieces by Henry that rank among the very earliest English part music for instruments alone. Although Henry’s music appears robust or plaintive, as the case may be, “they have a memorable beauty all their own.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Henry VIII: Without Discord (Alamire; David Skinner, cond.)