Marguerite Long

Credit: http://bn.org.pl/

Sergei Rachmaninoff (Russia, 1873-1943) Regarded as one of the greatest pianists of the twentieth century, Rachmaninov had legendary technical facilities and rhythmic drive, and his large hands were able to cover the interval of a thirteenth on the keyboard. Today his piano music is amongst the most well-loved and widely-performed in the standard repertoire, yet in the 1950s the Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians dismissed it as “monotonous in texture…..consist[ing] of mainly of artificial and gushing tunes….”. He was composing at a time when music was undergoing huge sea-changes (atonality and the development of the 12-note tone row, for example), yet he remained true to his own compositional vision and his music is unashamedly Romantic, full of sweeping melodies and rich textures. Even in his miniatures (the Preludes, Moments Musicaux, Etudes-Tableaux) his music displays his understanding of all the elements of music, and seems to express the vastness of the Russian landscape. It has a visceral, deeply honest quality which makes it incredibly rewarding to play. His own playing style was extremely clean and precise, with a luminous cantabile tone.

Rachmaninov plays Rachmaninov – Prelude in G Minor

Marguerite Long (France, 1874-1966) Regarded as France’s foremost woman pianist during the first half of the twentieth century, Marguerite Long was taught initially by her sister. In 1889, even before completing her studies at the Paris Conservatoire, Long won first prize and immediately started forging an international career as soloist and teacher. She was particularly devoted to performing music by her fellow compatriots Fauré, Debussy, Satie, Roger-Ducasse, Ravel, Milhaud, and Poulenc. She premiered Ravel’s Piano Concerto in G which was dedicated to her, and she later wrote a volume of memoirs on Ravel which contains detailed advice on the interpretation and performance of his piano works. She was one of the last pianists to study with Debussy, though at first she resisted playing his music, claiming its style was too enigmatic. A respected teacher herself, she developed her own method of mastering the technique jeu perle, typical of the French piano style in which each note is crisp and pure like a pearl in a string.

Long plays Debussy

2 Arabesques

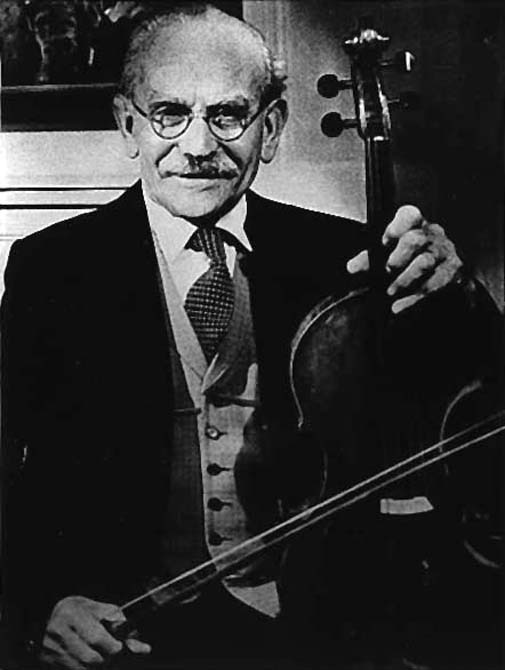

Alfred Cortot

Credit: http://www.ecolenormalecortot.com/

Cortot plays Chopin

Ballade No. 1 in G Minor, Op. 23

Clara Haskil

Credit: http://www.bach-cantatas.com/

Haskil plays Schumann

Kinderszenen (Scenes of Childhood), Op. 15

Sviatoslav Richter (Russia, 1915-1997). Richter seemed to be superhuman, possessed of a formidable technique, and huge hands, which enabled him to play almost anything and the imagination to create vivid colours and nuances. Fearsomely intellectual, he chose to perform pieces exactly the way composers had written them, with vertiginous speed and precision. He had no formal training as a pianist until he entered the Moscow Conservatory in 1922 where he studied under Heinrich Neuhaus, who said of him “[he] treated each composition like a vast landscape, which he surveyed from great height with the vision of an eagle, taking in the whole and all the details at the same time. He played like no one I had ever heard, and there was nothing I could teach him.” He never rested on the laurels of his success and continued to expand his repertoire throughout his life. His concerts, often in near darkness, were intense, meditative, almost religious experiences for the listener, while his performances of the late sonatas of Beethoven and Schubert are profound and philosophical.

Richter plays Beethoven

Piano Sonata no. 32, op. 111

Alfred Brendel

Credit: http://i.telegraph.co.uk/

Brendel plays Haydn

Piano Sonata nº 59 in E flat, Hob. XVI:49

Glenn Gould (Canada, 1932-82) It is perhaps a mark of Gould’s artistic status, and the enduring power of J S Bach’s music, that his recording of the first Prelude and Fugue from Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier was included on the Voyager spacecraft. His two recordings of the Goldberg Variations are regarded by many as the benchmarks for this work. He was able to create a remarkable resonance through the care with which he placed each note, and he displayed a deep understanding of Bach’s counterpoint as well as creating a clear narrative line through the whole piece.

A noted eccentric and hypochondriac – he wore overcoat, gloves, scarf and hat whatever the weather, refused to shake hands with people in case it damaged his own hands, and took copious amounts of pills for real and imagined ailments – he retired from performing in 1964 when he was only 31, regarding public concerts as an anachronism and the audience as innately hostile. Instead he devoted himself entirely to recording. He felt the opportunity to manipulate the tape was part of the creative process and enjoyed having total artistic control over the recording. In many ways, he was ahead of his time and would probably have been fascinated by the ability afforded by today’s technology to manipulate and minutely adjust recordings as well as the opportunity to share music and create personalised playlists via streaming services such as Spotify.

Gould plays Bach

The Well Tempered Clavier

Martha Argerich (Argentina, 1941-). The phenomenal talent of Martha Argerich first came to worldwide attention in 1964 when she won the International Chopin Piano Competition at the age of 24. Today her reputation is such that she can sell out the biggest venues in a matter of moments. She combines astonishing technical prowess with a fierce intellect and an unaffected interpretation which brings great naturalness to her performances: when she plays she appears to embody the music rather than simply interpret it. She made her debut at the age of eight in Buenos Aires and by the time she was 16 she was winning competitions. She has a broad and varied repertoire and is a noted collaborator with other great artists such as Daniel Barenboim, violinist Gidon Kremer, cellist Mischa Maisky, and conductor Charles Dutoit (to whom she was briefly married). She is one of the more enigmatic personalities on the international piano circuit, due in part to her reclusive shunning of the press, and, haunted by her insecurities, can be an erratic performer, famously prone to canceling concerts at the last minute which only adds to her mystique.

Argerich plays Prokofiev

Toccata in D Minor, Op. 11

Maria João Pires (Portugal, 1944-) Her performances and recordings of Mozart and Schubert in particular are cherished and celebrated for their exquisite intimacy, lucid elegance and stylistic refinement, yet Maria João Pires is a modest and self-effacing pianist. She emphasises the spiritual element of the music she performs, searching for hidden meanings and revealing a remarkable reverence, most evident in her performances of Mozart, regarding herself as a channel for the composer’s ideas. Her emotional intensity is revealed in great variety of tone, touch and expression, ranging from gossamer lightness to an imposing monumentality. A performer who is not keen on the concept of the “professional concert pianist”, and who shuns the limelight, she has always insisted on doing things her way, preferring to devote much of her time to encouraging and supporting young artists through her Partitura Project at the Queen Elisabeth Music Chapel in Belgium, which seeks to thwart the effects of the “star system” prevalent in many conservatoires and international music competitions by encouraging reciprocal listening and support between generations.

Pires plays Mozart

Piano Sonata No. 11 in A Major, K. 331

Stephen Hough (England, 1961 – ) Stephen Hough is a musical polymath. In addition to his distinguished performing career, he is an acclaimed composer, in the tradition of the great composer-pianists Liszt and Rachmaninov. He is also a noted writer on music, contemporary culture, philosophy and religion, and his wide-ranging interests allow him to see beyond the music to create perceptive and deeply thoughtful performances. In addition to highly-praised performances of core repertoire, he has an interest in contemporary and neglected nineteenth-century piano music. Like Rachmaninov before him, he boasts scintillating technique, a sparkling sound, and clarity of line, and his playing integrates his broad outlook, vivid imagination and profound intelligence.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Hough plays Hough

Piano Sonata, “Broken Branches”

It seems incredible to me that Murray Perahia did not make this list.

Perahia at his last recital at Carnegie hall in 2017 has forgotten half of the notes …. let him go quietly to a retirement home in Florida or Israel

What a strange and vulgar comment. All the pianists listed here have or will reach a point when their mental or physical capacities decline to the point of failure, just like all other people. This has no bearing on the artistic achievements of Perahia’s career, which has been assessed by plenty of other great musicians—who won’t “retire in Florida or Israel”—to have been one of the best of his generation.

Alex must be mentally ill to describe Mr Perahia in this terms. Today he still teaches students, who are grateful to learn his musicianship.

To the list of great pianists I think Josef Lhevinne certainly deserves consideration.

Your list is more notable for the pianists it excludes, rather the ones that are included. Regardless whether or not the latter group was chosen by dint of ignorance or personal preference, it is probably in your best interest to title your selection as the pianists that you particularly like, without referring to comparative greatness.

You are right Sacha. The list is quite arbitrary. Stephen Hough? Well you have to support your fellow country men. Peraiah ???? Horowitz? Pletnev? Where?

Love this kind of list which let you explore more artists than just repeating those famous name! Thank for the post!