Paul Reale

For American composer Paul Reale—born in 1943 in New Jersey—the “most significant element which is under the control of the composer is time. By controlling the way the listener perceives time, a well-written musical composition garners the full attention of the listener to the point that there is no awareness of time passing.” Reale, a student of Otto Luening and Chou Wen-Chung has been lamenting the decline of classical art music, and he primarily sees three reasons: “the rejection by composers of major traditions from the past; the decision of orchestras and other performing groups to concentrate on traditional repertory; and the retreat of composers into universities where their creative energies have come to be focused on avant-garde styles fitting more readily into the compendious concept of research, leaving behind the established canons of Western music tradition.” As such, Reale set out to compose music that “provides the listener with a broad panoply of listenable, challenging 20th-century piano music from the past and present which embodies the elements that fine music has always had.” One of those attempts is featured in the “Sonata Brahmsiana” composed in 1985/86. According to the composer, the work “tries to capture the sweep and energy of the Brahmsian piano phrase, within the broad boundaries of an eclectic pitch language.” There has been some debate whether Reale actually managed to successfully imitate the musical style of Brahms, but he certainly infuses all movements with plenty of Brahmsian gestures, rhythms and sounds.

Paul Reale: Piano Sonata No. 3, “Sonata Brahmsiana” (John Jensen, piano)

Ottorino Respighi

For Ottorino Respighi (1879-1936) Italian cultural identity was securely situated in the artistic expressions of the Italian Renaissance and Baroque. His historicist interest in the music of the past emerged not only in critical editions of the music of Claudio Monteverdi and Antonio Vivaldi, but also manifested itself in his own compositions. He tried to reconcile Italian musical traditions with Romantic, impressionist and neo-classical streams that were fashionable in Europe, steering well clear of atonality and serialism. He strongly believed that the Italian genius for music was found in melody and clarity, and that Gioachino Rossini represented both aspects. In 1925, he turned to a volume of Rossini piano music called Les Riens (Trifles). He selected four pieces and transcribed them for a suite entitled “Rossiniana.” The suite pays tribute to Rossini through the musical landscape of Italian song and dance, including a waltz-like siciliano in the traditional Venetian gondolier’s song and a high-spirited Tarantella.

Ottorino Respighi: Rossiniana (Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra; JoAnn Falletta, cond.)

Darius Milhaud

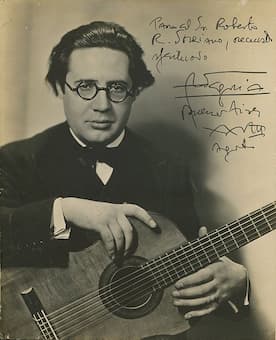

Alongside de Falla, Ibert, Britten, Ginastera and many others, Darius Milhaud (1892-1974) wrote a single piece for solo guitar. He, alongside his colleagues, was inspired by the phenomenon of twentieth-century Spanish guitarist Andrés Segovia (1893-1987).

Andrés Segovia

The rise in status and the popularity of the classical guitar are intricately connected with this greatly admired artist and exquisitely gifted virtuoso. In no time at all Segovia attracted the attention of countless composers who set to work on expanding the repertoire of the instrument. Milhaud’s Segoviana has been described as one of the most intriguing pieces in the guitar repertoire, “providing an agile collage of gestures…with a character to seemingly elude even the most experienced performers.” The work dates from 1957, but as far as we know, Segovia never performed this composition, which was after all dedicated to him. It was only premiered in 1996 by one of his most illustrious students, Eliot Fisk. Milhaud was not the only composer shunned by Segovia, as he also ignored Schoenberg’s Serenade of 1923, Krenek’s Suite for Guitar and Frank Martin’s Quatre pièces brèves of 1934.

Darius Milhaud: Segoviana, Op. 366 (Turibio Santos, guitar)

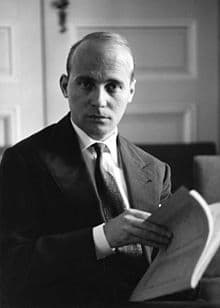

Hans Werner Henze

In 1967 we commemorated the 200th anniversary of Georg Philipp Telemann’s death.

Throughout his long and industrious career, he wrote well over 3000 works, and 18th century critics unanimously considered him among the best composers of his time. Yet by the early years of the 19th century, appreciation of Telemann’s music was in rapid decline. The main criticism turned out to be rather tongue in cheek. “In general,” a music historian wrote, “Telemann would have been greater had it not been so easy for him to write so unspeakably much. Polygraphs seldom produce masterpieces.” The composer Hans Werner Henze (1926-2012) thoroughly disagreed with that particular assessment, and his Telemanniana is a musical treasure shimmering with all the colors of the orchestra. Henze took Telemann’s final Nouveaux Quatuors en Six Suites, originally scored for flute, violin, violoncello and basso continuo, and dressed it “in a new garment of sounds by a faithful transcription for orchestra.” The result is a delightful musical jewel that retains the dance-like and graceful character of the original and infuses it with the prism of 20th century orchestral sound.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Hans Werner Henze: Telemanniana (North West German Philharmonic Orchestra; Gerhard Markson, cond.)