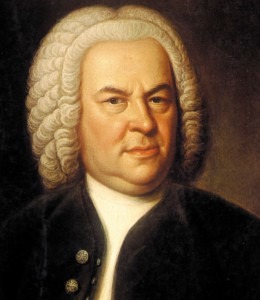

J.S. Bach

Within the enormous variety and diversity of musical compositions, only a select few ever manage to withstand the test of time. One such work is the “Chaconne” from the Partita No. 2 in D minor for solo violin, composed by J.S. Bach between 1717 and 1723. Famously, Joshua Bell described the work as “not just one of the greatest pieces of music ever written, but one of the greatest achievements of any man in history. It is a spiritually powerful piece, emotionally overwhelming, structurally perfect.”

The test of time, however, does not merely rely on contemporary testimonials; it also derives from the way a piece of music is handed from one generation to the next. In many cases the piece undergoes a process of transformation before it reappears in a variety of different guises and shapes, or what in musical terms are called transcriptions or arrangements.

J.S. Bach: Violin Partita No. 2 in D minor, BWV 1004 – V. Chaconne (Yehudi Menuhin, violin)

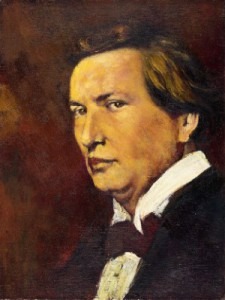

Johannes Brahms

When Johannes Brahms stumbled upon Bach’s “Chaconne” in 1877, he simply couldn’t believe his eyes. “On one stave, for a small instrument, the man [Bach] writes a whole world of the deepest thoughts and most powerful feelings. If I imagined that I could have created, even conceived the piece, I am quite certain that the excess of excitement and earth-shattering experience would have driven me out of my mind.” Since the piece had already been composed, Brahms did the next best thing and produced a transcription of for piano left-hand.

Musical myth suggests that Brahms made the transcription as a consequence of a supposed injury to Clara Schumann’s right hand. However, in a letter dated 6 July 1877, Clara Schumann explains “just think, on the day of my arrival here [Kiel], when I was opening a drawer I strained a muscle in my right hand, so you may imagine what a glorious refuge your Chaconne has been to me.” The earnestness with which Brahms went to task on his transcription — he compared the complexity and intricacies of producing his version to the mythical tale of the fifteenth-century navigator Christopher Columbus, who to the supposed amazement of Spanish courtiers was able to stand an egg on end by slightly cracking the shell at one of the poles — has been described as “faithful to the point of severity.” His absolute fidelity to the melody and rhythm, with the occasional filling-out of the harmonic progression, was according to Clara Schumann a faithful attempt to reproduce the sound of the violin on the piano. “You alone could have accomplished such a thing,” Clara writes, “however you came to think of it, it amazes me.” Brahms apparently took special pleasure and satisfaction from his self-imposed and presumed historically justified restrictions and limitations that merely allowed for the addition of performing indications for phrasing and dynamics. “There is only one way in which I can secure undiluted joy from this piece, though on a small and only approximate scale,” Brahms writes to Clara, “and that is when I play it with the left hand alone.” Scholars have persuasively argued Bach’s exemplary value for the nineteenth-century transcribers and arranger who “transformed the invention of others by intervening against the received idea behind a style. Bach not only licensed arrangement and re-composition for an age of individuality, but provided a model for how any apparent incompatibility might be overcome.” For Brahms, however, the resolution to any perceived incompatibility was not to be solved by realizing the potentialities of what was not explicitly written in the musical text, but to pledge an even sterner allegiance to a translation that as closely as possible resembled what he perceived to be a perfect union between the object and event status of Bach’s music.

Johannes Brahms: 5 Studies for the Piano, Anh. Ia/1: No. 5. Chaconne by J.S. Bach (Anna Vinnitskaya, piano)

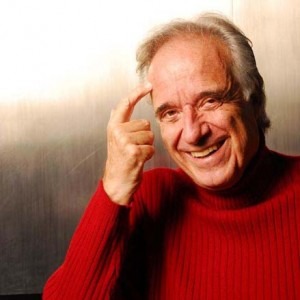

Ferruccio Busoni

However, Ferruccio Busoni was guided by a slightly different aesthetic when he made his two-hand piano, and highly operatic arrangement of the Bach “Chaconne” in 1893. Busoni essentially regarded all works as transcriptions, as the ideal prototype could not be exclusively identified with a musical score or with a performance. Since the musical text imperfectly reflected the intentions of the composer, it was left to the performer or arranger to access the ideal version through the musical text.

J.S. Bach: Violin Partita No. 2 in D Minor, BWV 1004: V. Chaconne (arr. F. Busoni for piano) (Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, piano)

Paul Wittgenstein

Paul Wittgenstein — who lost his right hand in WWI but continued his career as a left-hand pianist — must have had been guided by similar considerations as he made a transcription of the Bach/Brahms “Chaconne” for his left hand.

In his three-volume School for the Left Hand, published by Universal in 1957, he objectifies his editorial revisions as follows: “Brahms’s arrangement is itself a transcription of a violin composition, and in the case of such transcriptions from one instrument to another certain latitude is not only permissible but also even necessary. Brahms himself made use of this privilege by setting the Chaconne one octave lower. However, because of this undoubtedly correct change which alone, so to say, placed this piece on firm ground, making possible the full use of the piano bass, the music remains exclusively in the tenor register of the piano. This results in a certain monotony of tone, which I have tried to overcome by making certain changes.”

The monotony he encounters in Brahms’s transcription is the result of an austere pledge of fidelity to an inviolable Bach text, according to Wittgenstein, prevented Brahms from exploring the full possibilities of the keyboard. In his own arrangement, Wittgenstein immediately extends the range by adding a true bass, and introduces the technical solution designed to overcome his own physical limitation. Whereas Brahms’ transcription persists in its attempt to reproduce the slim and vocal quality of the violin sound, Wittgenstein developmentally, in the style of a gradually unfolding drama, places ever-increasing demands on the performer. Here Wittgenstein appropriates the virtuoso and dramatic aspect of Busoni’s arrangement, while retaining the content that Brahms was trying to preserve. Just imagine Wittgenstein at the piano, sitting on Busoni, who in turn is sitting on Brahms. All three gentlemen are now sitting on poor old J.S. Bach and are trying to speak with his voice!

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Brahms/Bach: Partita No.2 in D minor, BWV 1004: V. Chaconne (Arr. Paul Wittgenstein)

Michelangeli’s rendition is great!

Busoni did make a piano-roll, with much less pedaling, that sounds much different from other pianists. I am not saying that who plays better but it’s the transcriber who played it.

Wittgenstein playing his own transcription is wonderful!

What about Brahms! Try Grigory Sokolov’s version, if I may!