Brian Ferneyhough: Carceri d’invenzione cycle

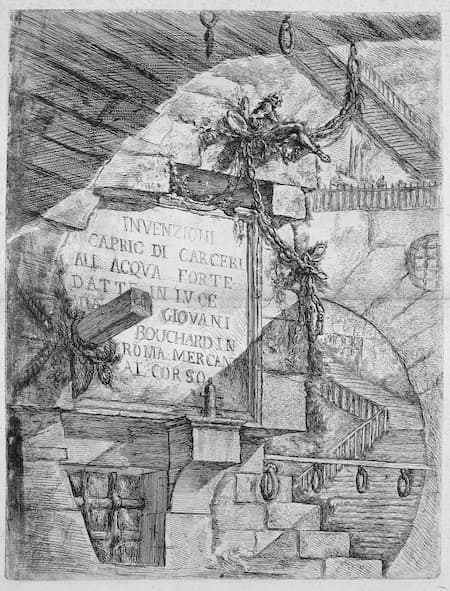

Endless staircases, blocked passages, heavy machinery with unknown power, figures trapped in dead hallways: you’re in the world of Giovanni Battista Piranesi and his world of imaginary prisons. The Carceri d’invenzione of Piranesi were begun in 1745 and the first prints appeared in 1750, followed by a second edition in 1761.

Piranesi: Invenzioni Capric di Caceri (1750). Title page

The images are populated by our fears – underground passages of great construction, wooden walkways above terrible depths, bound prisoners in precarious positions.

Piranesi: Plate 10: Prisoners on a Projecting Platform (1761)

The architecture is monumental and creative, but can only be imagined as having been built with the worst intentions.

Piranesi: Plate 14: The Gothic Arch (1761)

Piranesi is most famous for his views of classical antiquity around Rome: preserving the extant structures in his drawings with a deep understanding of the methods of construction that have lasted over the centuries. At the same time, he had to use his imagination to recreate the world of the past in a way that would permit viewers to place themselves into the space. When it came to creating his set of very unusual prints about his imaginary prisons, it was imagination that came to the fore.

Every drawing has figures placed in them to help us imagine the scale of his monumental spaces. In The Gothic Arch, you can see figures on the staircase and on the landings that show us that the bottom arch, for example, is about 3 figures high, or about 6 meters high – and that’s just the one small arch in an enormous space.

The British composer Brian Ferneyhough was inspired by Piranesi’s drawings to create his Carceri d’invenzione cycle. If you consider the composer as someone whose work moves between formal structure and fantasy, then Piranesi’s work fits that model.

Ferneyhough’s Carceri d’Invenzione cycle was composed between 1981 and 1986. It is made up of 7 compositions for solo instruments, solo instruments and chamber orchestra and works for chamber ensembles of various sizes.

Superscriptio for solo piccolo

Carceri d’Invenzione I for ensemble

Intermedio alla ciaccona for solo violin

Carcari d’Invensione II for solo flute and chamber orchestra

Etudes transcendentales for flute, oboe, soprano, harpsichord and cello

Carceri d’invenzione III for 15 wind instruments and percussions

Mnemosyne for bass flute and tape

The composer found Piranesi’s work a ‘masterly deployment of layering and perspective which gave rise to the impression of extraordinary immediacy and almost physical impact.’ It also reflected his believe that ‘all expression in art in some way derives from limitation.’ One of the indicative ideas in Piranesi’s work is that of his lines of perspective: the multiple lines, they are often in conflict, and sometimes seem to carry one beyond the edge of the page. In the same way the composer has his limitations in the range of his instruments and of the skills and technical abilities of his performers. Time flow, in terms of measures with changing meters, measure length, and use of note subdivisions, can change in an instant.

Superscriptio, for solo piccolo, inspired one writer to say that it ‘…focuses around the idea of borders and boundaries evoked by the high sound of the piccolo. It almost seems to reflect beyond these borders which fade in and out of view,’ and we see these same ideas in the Piranesi drawings – how far back to these prisons extend?

Piranesi: Plate5: The Lion Bas-Reliefs (1761)

Carceri d’Invenzione I is a work for chamber ensemble.

Brian Ferneyhough: Carceri d’Invension I (Ensemble Contrechamps; Nieuw Ensemble; Jurjen Hempel cond.)

In this premiere recording of Carceri d’invenzione II, the flutist is challenged by range, by time, and technique. The performer is asked to create whistle tones, multiphonics (playing and singing different notes at once), and microtonalities, all the while dealing with tempo and rhythmic subdivisions.

Brian Ferneyhough: Carceri d’invenzione IIa (Roberto Fabbriciani, flute; RAI Symphony Orchestra, Milan; Marcello Panni, cond.)

The final work, Mnemosyne, is named for the goddess of memory. Her daughters were the 9 muses, including Euterpe, the muse of music, song and lyric poetry. Across all the parts of the Carceri cycle, the flute has been the unifying instrument – from the piccolo in the first one to the bass flute in the final one.

Simon Vouet: Euterpe (17th century)

Brian Ferneyhough: Mnemosyne (Carin Levine, bass flute; Brian Ferneyhough, pre-recorded tape)

These are difficult works that illustrate a difficult concept in art. Imagination is to the fore and reality has to take a back seat in these works. Piranesi’s imaginary prisons force us to try and resolve his problems in perspective, but only at the cost of our own rationality. And so Ferneyhough challenges in a similar way – the limitations of the instruments and the technical demands on the performer will also give us a changing perspective.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Personally I dislike his pretentious unfounded alien-styled inhumane chaotic pseudo-random material, which exists only for it’s own sake and creates sensory responses that are not of the composer’s intention, but just happen to occur.

Make no mistake: Ferneyhough is no real composer; and the fact that this has never been accordingly stated or criticized shows the times in which we live: Feed the people any rubbish, with just a hint of added intellectual superiority and they’ll believe it and worship you ‘message’.

… Ferneyhough… the charlatan king of pretentious wishful implication

He’s pretty frequently maligned. You’re not the first to the party. He’s hardly worshipped.

So are you making that comment based on your notions “personally” or are you delivering your verdict with “objective” God-like certainty (“make no mistake”)?