Inspirations Behind Cheryl Frances-Hoad’s Melancholia

After the death of his father, Edvard Munch (1863–1944) made a vow in his diary: “There should be no more pictures of interiors, of people reading and women knitting. / There would be pictures of real people who breathed, who suffered, felt, loved. / I felt impelled – it would be easy. The flesh would have volume – the colours would be alive”.

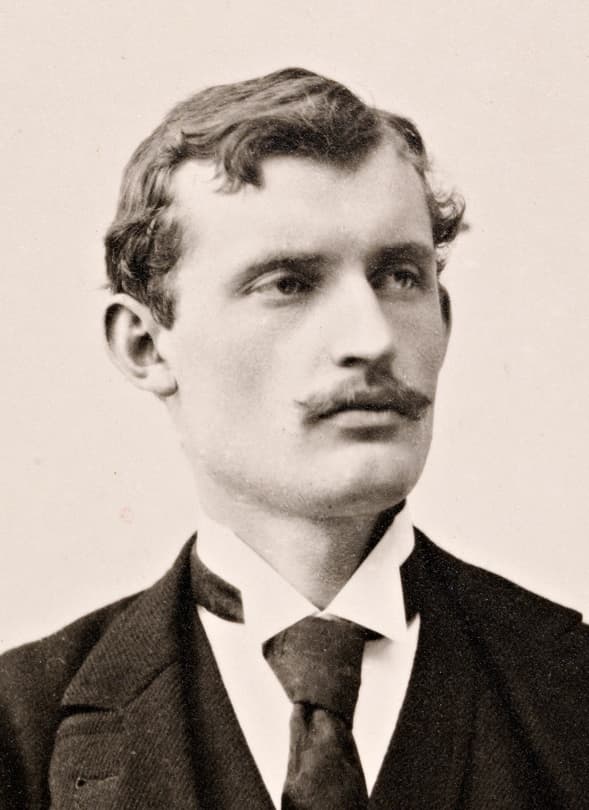

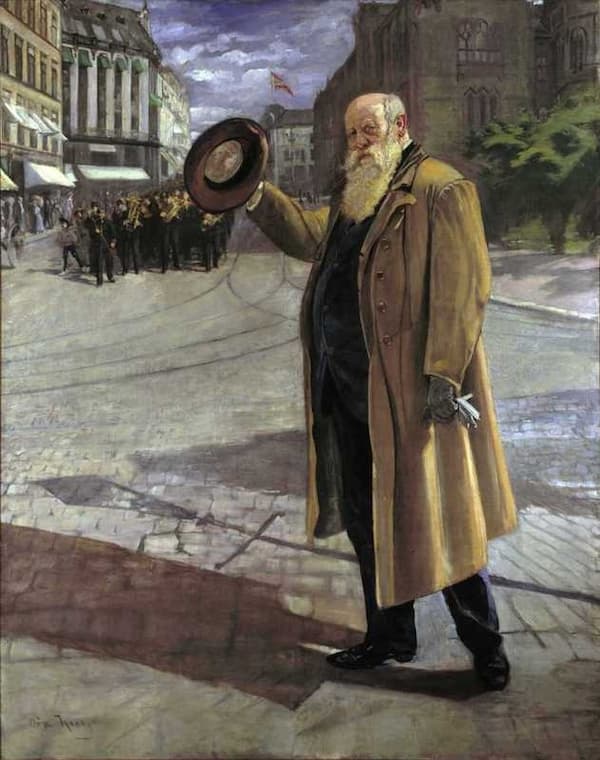

Portrait of Edvard Munch (1863-1944) c. 1889. National Library of Norway

In his house in Berlin, he started to put a decade’s worth of art on the wall – creating what was known as the Frieze of Life. He had been invited to Berlin first in 1892 by the Verein Berliner Künstler (Association of Berlin Artists) to do an exhibition; unfortunately, the Association held an extraordinary meeting and voted, 120 to 105, to close the exhibition after heavy criticism in the press. It had been open only a few days. It left Munch wondering why he’d been invited. The younger artists were outraged by this and split from the main association, forming the Berlin Secession. When Munch returned to Berlin in 1902, it was these younger artists who supported his work.

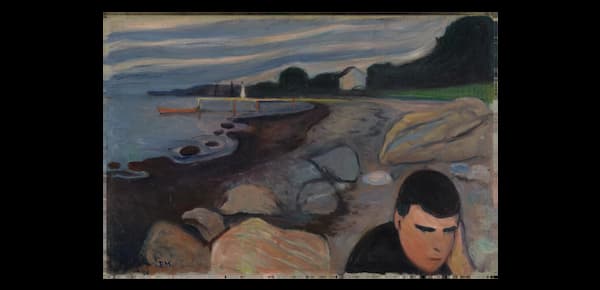

In his room, the Frieze broke into 4 categories: Seeds of Love, The Flowering and Passing of Love, Anxiety, and concluding with Death. Where the first group was about the start and infatuation of love, the second section shows life when the initial passion fades. In many of these pictures, women are in positions of power, and the men are marginalised. Part of this series is his painting Melancholy, which had formed part of the failed 1892 exhibition.

Edvard Munch: Melancholy, 1892 (Oslo: Nasjonalmuseet)

This idea exists in several versions, both as paintings and as woodcuts.

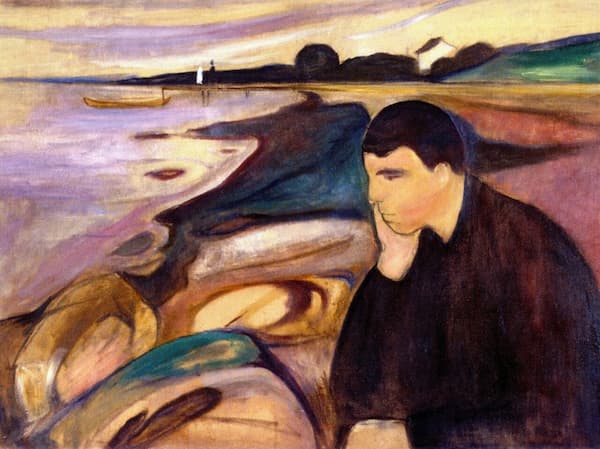

Edvard Munch: Melancholy, 1894 (private collection)

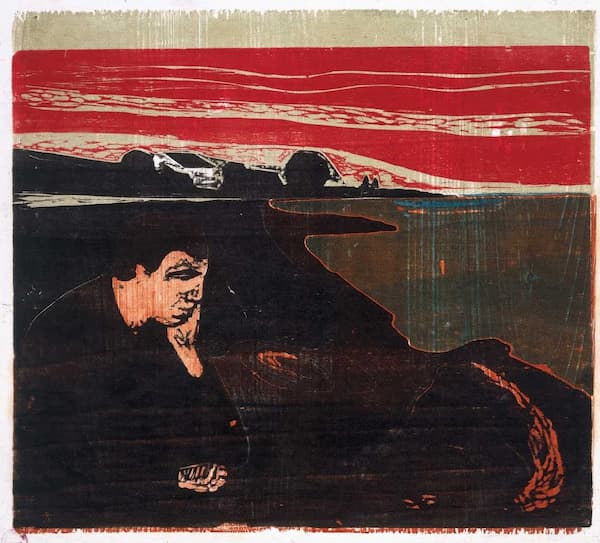

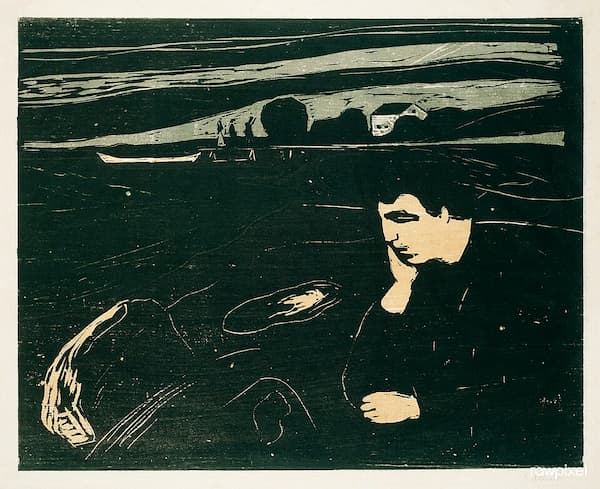

Edvard Munch: Evening (Melancholy I), 1896 (Oslo: Munch Museum)

Fearing his 1896 woodcut had gotten lost, Munch redid it, this time not reversing the image.

Edvard Munch: Evening (Melancholy III), 1902 (Art Institute of Chicago)

In the 1892 painting, the man in the foreground is Munch’s Nihilist friend, Jappe Nilssen, who was suffering from jealousy while involved in a love affair with Norwegian artist Oda Krohg, wife of artist Christian Krohg.

Jappe Nilssen and Oda Krohg, 1891

Oda Krohg: Portrait of Christian Krohg, ca 1903 (Oslo Museum)

Christian Krohg: Oda Krohg, 1888 (Oslo: Nasjonalmuseet)

As the third man in their marriage, he was in a precarious position as shown in the painting. They form a couple in the background, and he’s down the shore with his head in his hand, in a thinking position. On the pier behind him are three figures: a sailor carrying oars, a man, and a woman in a white dress.

In the 1894 painting, Nilssen is much more prominent, and the man with the oars has disappeared, and the man and woman have reversed their places. In the two woodcuts, the first has the image reversed (as it would be if carving a woodcut with the painting in front of you – it would then print in reverse), and the two figures are not clearly delineated. In the 1902 woodcut, he follows the 1894 painting but has added back the sailor and his oars.

In the painting, Munch has softened the colours and stylised the form. The man’s head and the boulders are not unalike. The landscape is based on the coastline at Åsgårdstrand, on the coast to the south of Oslo.

English composer Cheryl Frances-Hoad (b. 1980) used the painting as inspiration for her 1999 piano trio Melancholia.

Cheryl Frances-Hoad

The work is made up of a theme and 3 variations. The Theme is given to the violin and cello in unison, with the piano playing repeated chords or being silent. The silences are as important as the chords: where the chords are the controlling harmony of the work, the silences become increasingly important, particularly as the thematic line breaks down into more silence itself. The tempo indication (Largo trascinando) means ‘slow and dragging’.

Cheryl Frances-Hoad: Melancholia – Theme: Largo trascinando (London Mozart Trio)

In Variation 1, the strings take the chords from the piano, and the piano takes the melody in octaves. Through this variation, the piano becomes more active, driving to a brief climax.

Cheryl Frances-Hoad: Melancholia – Variation 1: Più mosso (London Mozart Trio)

The violin sits out Variation 2, which is given to the cello and piano only. The cello sings in a ‘long, meditative cantilena’ while the piano resumes the chordal textures it had in the Theme.

Cheryl Frances-Hoad: Melancholia – Variation 2: Meno mosso (London Mozart Trio)

Violin and piano are the focus of Variation 3, playing elaborations on the Theme. The cello comes in at the end, and the trio sweeps to a climactic end in fortississimo (fff). From there, the music winds down, but comes to an inconclusive end.

Cheryl Frances-Hoad: Melancholia – Variation 3: L’istesso tempo (London Mozart Trio)

The sadness in Munch’s picture and its unresolved emotion are clearly shown in Frances-Hoad’s piano trio. Each voice of the trio has its own path, as did the original 3 lovers, and they play off each other to tell their story. They support, but ultimately, they stand alone.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter